*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian.

“After their service in the Union armed forces during the great Civil War had ended, many of the veterans who survived the turmoil were mustered out of service and had gone home. Some of these men began to pine for the friendships and camaraderie that they had shared during the war. Veterans’ clubs began to spring up around the country. Many were local and most did not last very long but a few went on to become national organizations. One of these was the Grand Army of the Republic, or simply the G.A.R. … In 1866 the United States, now united as one nation as a result of the Union defeat of the Confederacy on the battlefield, was waking to the reality of the consequences and recovery efforts from a much different kind of war. In previous conflicts the care of the veteran warrior was the province of the family or the community. Soldiers in previous conflicts, when war had been a community adventure of local militia service, and their fighting unit had a community flavor, had gone off to fight until the next planting or harvest. But this time was different. The veterans had often endured bitter sacrifice, severe hardship and the bloodbath of industrialized warfare. By the end of the Civil War, military units had become less homogeneous; men from different communities and different states were brought together by the exigencies of battle where new friendships and lasting trust was forged. With the advances in the care and movement of the wounded, many who would have surely perished in earlier wars returned home to be cared for by a community structure weary from a protracted war and now also faced with the needs of debilitated veterans, widows and orphans. Veterans needed jobs, including a whole new group of veterans—the Africa American soldier—and his entire, newly freed, family. It was often more than the fragile fabric of communities could bear. The Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) was founded by Benjamin Franklin Stephenson, M.D. an army regimental surgeon, and Chaplain Reverend William J. Rutledge. Both men had served in the Civil War in the 14th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, and had been tent mates during Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Expedition to Meridian, Mississippi in February 1864. During the expedition they discussed founding an organization that the …” soldiers so closely allied in the fellowship of suffering, would, when mustered out of the service, naturally desire some form of association that would preserve the friendships and the memories of their common trials and dangers.””i

Affiliated GAR organizations were the National Women’s Relief Corps and the Daughters of the Union Veterans of the Civil War. Below are some examples of their materials found in MSS 319.

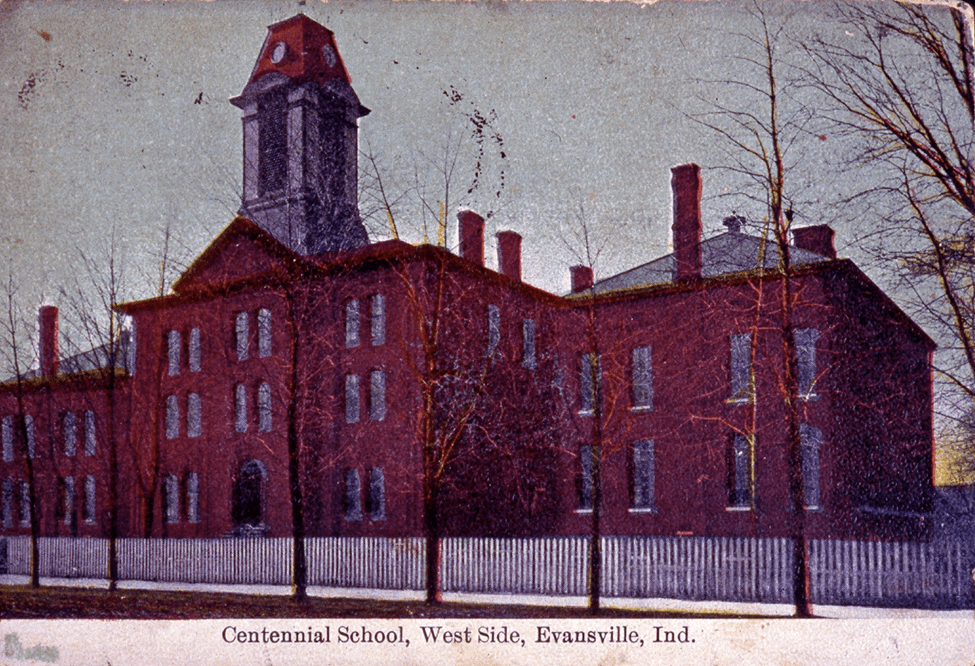

“The first national gathering of the Grand Army of the Republic was held in Indianapolis, Indiana and was called an Encampment just as in their soldier days, and all subsequent yearly national reunions were so designated, comprising 83 National Encampments from 1866 until 1949 the last Encampment held in Indianapolis, when only six members could be mustered.”ii Seen below is a program from a 1940 Indiana GAR encampment, held here in Evansville, and found in MSS 319.

The Grand Army of the Republic was far more than just a social club for Civil War veterans. It “set up a fund for the relief of needy veterans, widows, and orphans. This fund was used for medical, burial and housing expenses, and for purchases of food and household goods. Loans were arranged, and sometimes the veterans found work for the needy. The GAR was active in promoting soldiers’ and orphans’ homes; through its efforts soldiers’ homes were established in sixteen states and orphanages in seven states by 1890. The soldiers’ homes were later transferred to the federal government. … Members began discussing politics in local gatherings. A growing interest in pensions signaled the beginning of open GAR participation in national politics. The rank and file soon realized the value of presenting a solid front to make demands upon legislators and congressmen. The GAR became so powerful that the wrath of the entire body could be called down upon any man in public life who objected to GAR-sponsored legislation. In 1862 President Lincoln approved a bill granting pensions for soldiers who received permanent disability as a result of their military service. An 1879 act was liberalized to include conditions of payment. After that, the GAR became a recognized pressure group. The fate of some presidential elections was dependent upon the candidate’s support of GAR-sponsored pension bills. President Grover Cleveland was defeated for re-election in 1888 in large part because of his veto of a Dependent Pension Bill. President Benjamin Harrison was elected because of his definite commitment to support pension legislation. … The GAR’s principal legacy to the nation, however, is the annual observance of May 30 as Decoration Day, or more recently, Memorial Day. General John A. Logan, Commander-in-Chief of the GAR, requested members of all posts to decorate the graves of their fallen comrades with flowers on May 30, 1868. This idea came from his wife, who had seen Confederate graves decorated by Southern women in Virginia. By the next year the observance became well established. Members of local posts in communities throughout the nation visited veterans’ graves and decorated them with flowers, and honored the dead with eulogies. The pattern thus set is still followed to the present day. It was only after the first World War, when the aged veterans could no longer conduct observances, that the Civil War character of Decoration Day was replaced by ceremonies for the more recent war dead.”iii.

To the left here is the first volume of a 2 volume set entitled The soldier in our Civil War : a pictorial history of the conflict, 1861-1865, illustrating the valor of the soldier as displayed on the battle-field, from sketches drawn by Forbes, Waud, Taylor, Beard, Becker, Lovie, Schell, Crane and numerous other eye-witnesses to the strife. It was published in 1893. There are paper copies of this in MSS 319, but they are so fragile as to be unusable–the paper just disintegrates in your hands. Fortunately, it is available online for you to explore and enjoy, linked here:

“Another remarkable aspect of the Grand Army of the Republic is its benevolent treatment of the African American veterans of army and navy service. Close to 180,000 African Americans served nobly in the armed forces of the United States during the Civil War. Their service was gallant and contributed significantly to the Union victory and preservation of the Union. Dozens of African American veterans had received the Medal of Honor for valor in combat. From the foundation of the order in a time of institutionalized prejudice and overt racism, the order was color-blind, and officially treated all veterans equally. Most posts were integrated, although there were all ‘colored’ posts in larger towns and cities, formed where the African American veterans lived and where they felt most welcome and comfortable, similarly to all German posts, or all Navy or all Cavalry posts in certain metropolitan areas. Philadelphia is emblematic with thirty-six posts in a large city, including three ‘colored’ posts located in African-American neighborhoods, an all-German speaking post in the German ethnic area, a post exclusively for Naval veterans; one for cavalry, others which attracted certain localized military units, such as the Pennsylvania Reserves post and the Philadelphia Brigade post.”iv

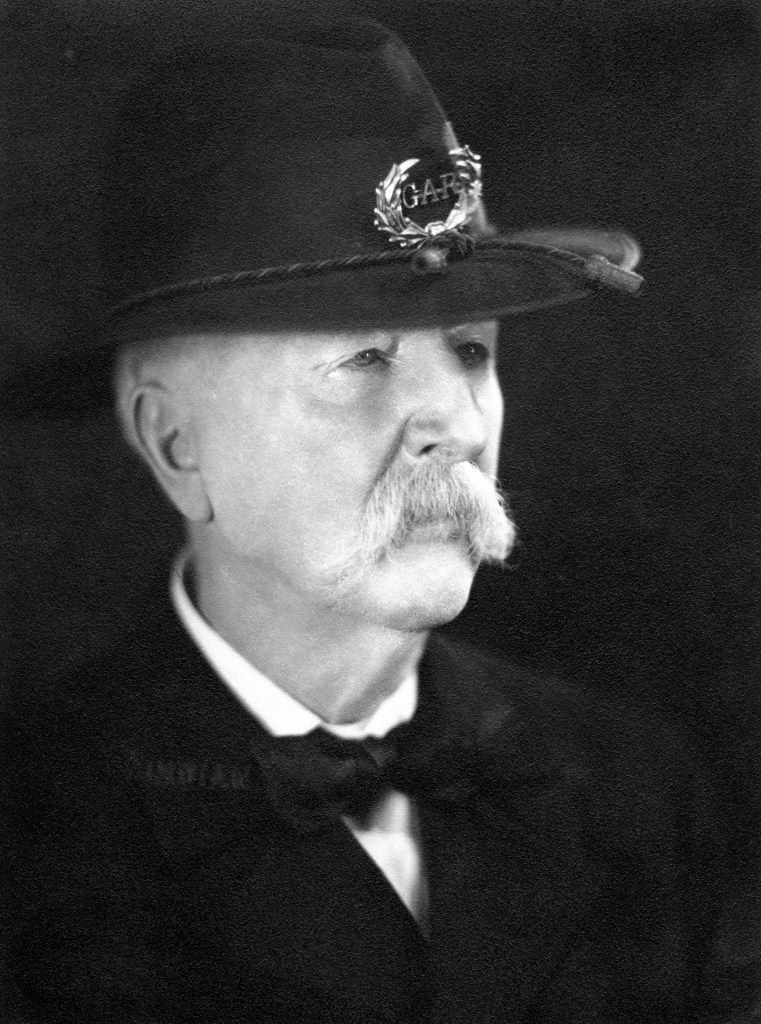

The following two photographs are also from MSS 319. Unfortunately, neither one is identified, but they are wonderful images of some of those who participated in the Grand Army of the Republic organization.

The organization officially dissolved in 1956 with the death of Albert Woolson at age 109, the last survivor of those who had served the Union cause.

Resources Consulted

iWaskie

iiWaskie

iiiGrand

ivWaskie

Leave a comment