*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian.

In the first half of the 20th century, Evansville was a bit of a sleepy southern town, suffering, as did the rest of the country, from the lingering Depression. December 7, 1941 changed that dynamic completely as Evansvillians geared up for war. “Vanderburgh County firms would, by March 1944, receive more than $600 million in defense contracts, more than any southern Indiana county. One study in 1981 indicated that forty-eight Evansville businesses did some sort of war work.”[i] One of these businesses was the Chrysler plant.

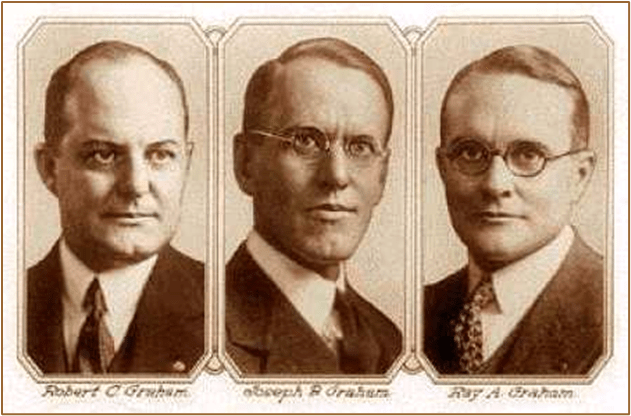

The story begins with three brothers: Robert, Joseph, and Ray Graham, who had a new business idea in 1919. “The brothers, especially Joseph, had always been fascinated with automobiles. Evansville seemed like an ideal city to start a factory. There were already many highly-skilled workers who had experience assembling tractors for Hercules Tractor Company. They planned to build the car bodies on site, using purchased motors and transmissions to complete assembly. Since they didn’t plan to manufacture their own engines or transmissions, the brothers began looking for quality parts that they could purchase. At the time, Dodge sold a line of highly-reliable motors, so they made a deal with their local Dodge dealer to supply them with the parts.”[ii] The business, Graham Brothers Truck Company, was very successful, and in 1924 the controlling interest was purchased by Dodge, later purchased by Chrysler.

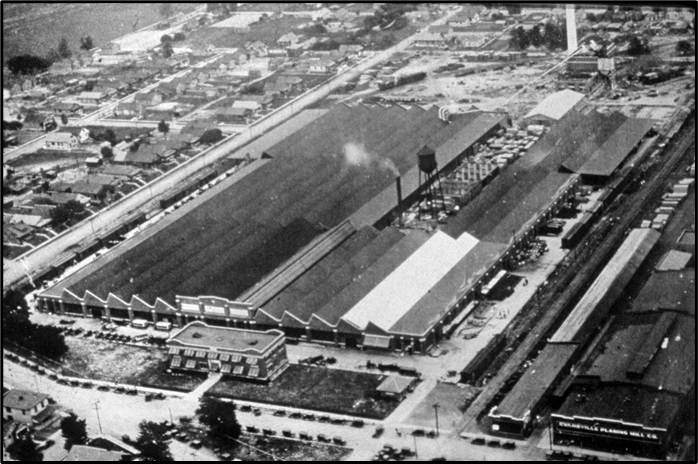

Graham Brothers Truck Company built its factory at 1625 N. Garvin St. in 1919. Chrysler was apparently able to make a go of the business after purchase and later expanded the footprint of the plant. This view is circa 1930.

As the 1930s progressed, worries grew about the aggressive role Germany was taking in Europe, with fears that WWI may not have been the war to end all wars. Business leaders were concerned that Evansville might get overlooked when it came to defense contracts. “As early as March 1941, a group was established called the Manufacturers Association Defense Committee, chaired by Thomas J. Morton, Jr., president of the Hoosier Lamp and Stamping Corporation, and dominated by the big local companies. By April, they had conducted ‘a survey of all available machine and personnel facilities within 50 miles of Evansville to make it possible to pool resources and get more defense work.’”[i] In July Evansville Mayor William Dress and several committee members traveled to Washington, D.C., where there were able to get a lengthy meeting with Sidney Hillman, associate director of the federal Office of Production Management (OPM). Hillman was very impressed with the presentation and “suggested that Evansville might be made a test city where an OPM engineer would assess the impact of prioritization of defense projects.”[ii] On September 8 the city was notified that it would indeed be a test city, with visits by OPM officials soon to follow. Evansville made a strong case for itself, and by October it was certified eligible for preferred consideration in the awarding of defense contracts.

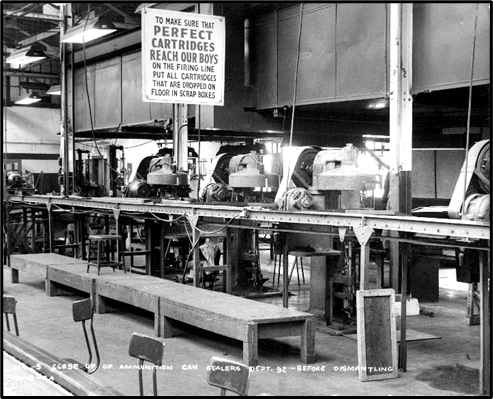

Events of December 7, 1941 proved that all this preparation and lobbying was not in vain. In future blogs I’ll discuss other defense contracts won by the city of Evansville, but for now, “Chrysler’s Plymouth assembly plant and Sunbeam Electric Manufacturing Company were both brought under the supervision of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the giant operation known as the Evansville Ordnance Plant was formed. Millions of tons of ammunition were manufactured in these factories, mostly for rifles, pistols, and machine guns. Before the war ended, Evansville Ordnance was listed as the biggest producer of small caliber ammunition in the United States.”[iii]

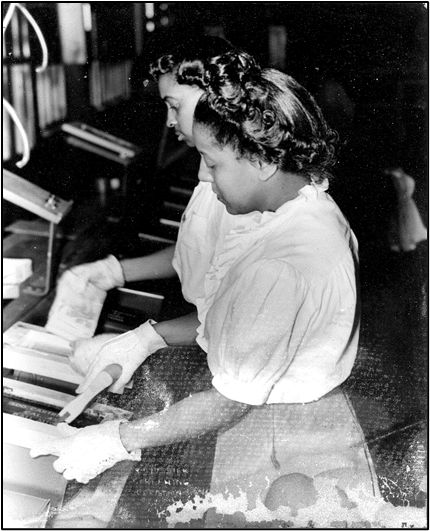

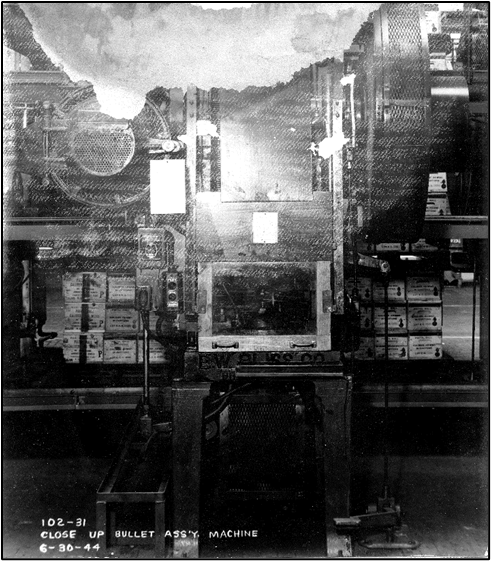

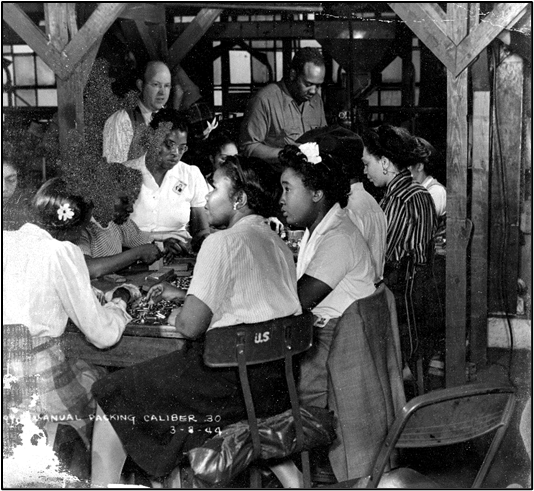

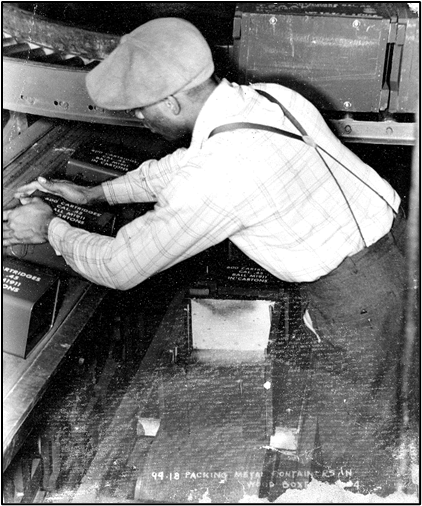

Chrysler president W.T. Keller was certain that the Evansville plant could meet any demand. Soon, Chrysler vice president Charles L. Jacobson, tasked with organizing and running the new operation, got an Army Ordnance team to inspect and approve the Evansville plant and a letter of intent for the making of 5,000,000 .45 caliber cartridges a day. One week later, Army Ordnance phoned Jacobson and increased the order to 7,500,000 rounds a day. Within twenty-four hours Army Ordnance again called and gave Jacobson another change order – increasing production to 10,000,000 rounds a day. Before the month ended, that number had jumped yet again to 12,500,000 rounds. Jacobson had doubts such an order could be fulfilled, but with Keller telling him to make it happen, Jacobson worked out a co-production agreement with Sunbeam, who had a plant near Evansville. On Feb. 18, 1942, Washington’s Birthday, the formal contract with the government was signed. The transformation of the Evansville plant from assembly line to arsenal began the next day. Cartridges made at the Evansville arsenal had seven parts, passed through 48 processing operations, and had to survive 334 quality control inspections. On June 30, 1942, the first bullets produced there were test fired. From June 1942 to April 20, 1944 when the contract ended, Chrysler’s Evansville arsenal produced 96 percent of the military’s .45 caliber cartridges: 3,264,281,914 rounds. Rejection rate of cartridges was less than .1 percent of production. It also produced almost a half-billion .30 caliber cartridges, hundreds of thousands of specialty rounds, reconditioned 1,662 Sherman tanks, rebuilt 4,000 Army trucks, delivered 800,000 tank grousers (track extensions for use in mud), and was preparing to make 7 million fire bombs when the war ended.[iv]

What’s more, a shortage of brass meant that they also had to figure out how to make bullets from steel, not brass. This was a very complicated process, but Chrysler workers managed to do this while maintaining a prodigious output.

This image provides a good overview of the types of work done at Chrysler. It is from a newsletter published by the Evansville Shipyard called The Invader. This image comes from the May 1945 issue, v.3:no.7, p. 20. It is from the Evansville in WWII collection of the Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library digital archive.

Here are some photos of the Evansville plant, all from UASC MSS 253, the Raymond Frederick Diekmann Chrysler Wartime Collection. Diekmann oversaw plant security at the Chrysler/Evansville Ordnance plant.

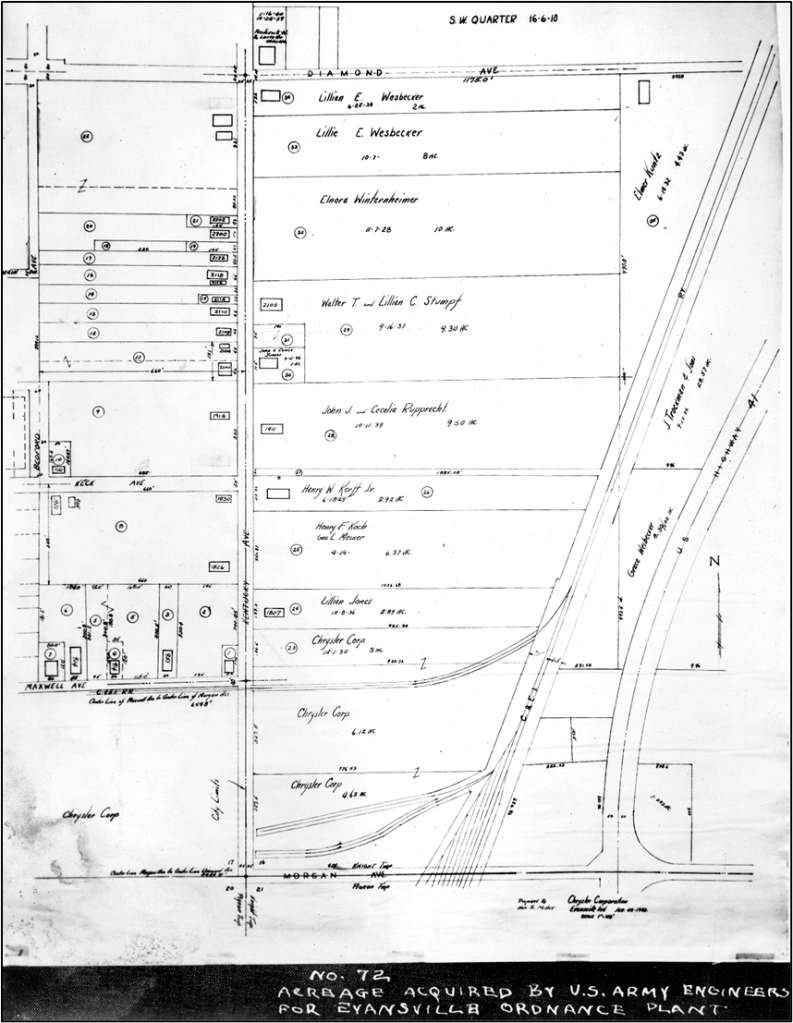

First is a map of the extra land acquired to retrofit the plant for defense work.

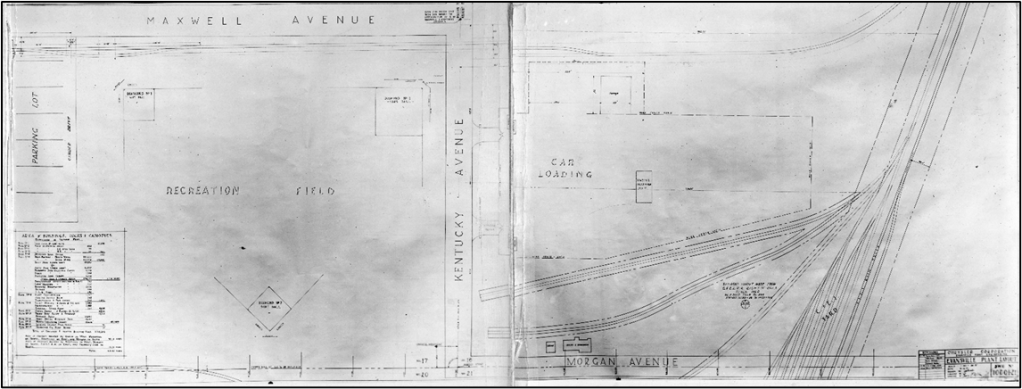

This is a map of the original Chrysler Plymouth plant itself. The image below is one long strip, too long to use here, so it’s been divided in half, with the second part below adjoining the top image to the right. All of this space was retrofitted for defense work, in addition to being greatly expanded and additional buildings constructed. For example, the recreation field seen here would have been taken over for defense work.

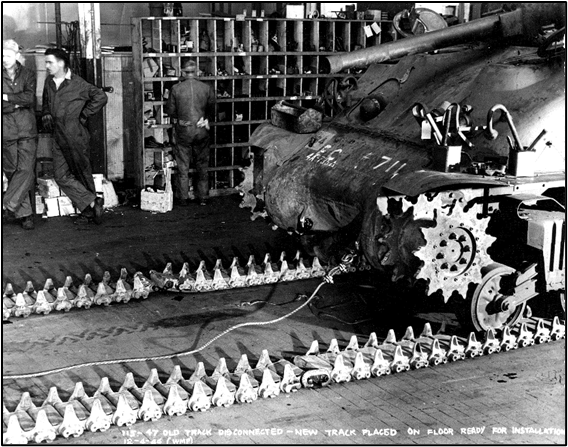

Those 1,662 Sherman tanks that were retrofitted at this facility arrived, some in poor condition, by rail. While awaiting repair or awaiting return to the front lines, they were kept in this tank storage yard seen below. In the foreground you can see some of the turrets. In the other two photos, the track or tread is being replaced.

Once the tanks were repaired, they had to be tested. The tank test track would have been a bit north of the plant, off Diamond Ave. This track still exists and can be driven on. The first image below is looking east from the southeast curve of the track.

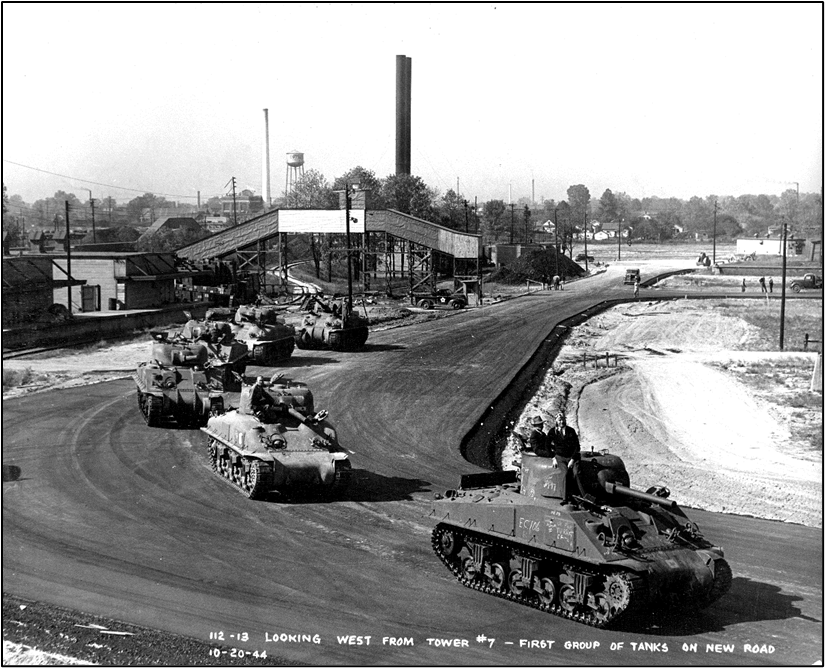

The image below depicts the first group of tanks on the “new road.,” October 20, 1944. Another interesting thing in this photograph is that light- colored arch in the center. That was part of the conveyor assembly that carried ammunition from manufacture at the Ordnance Plant to a separate packing plant.

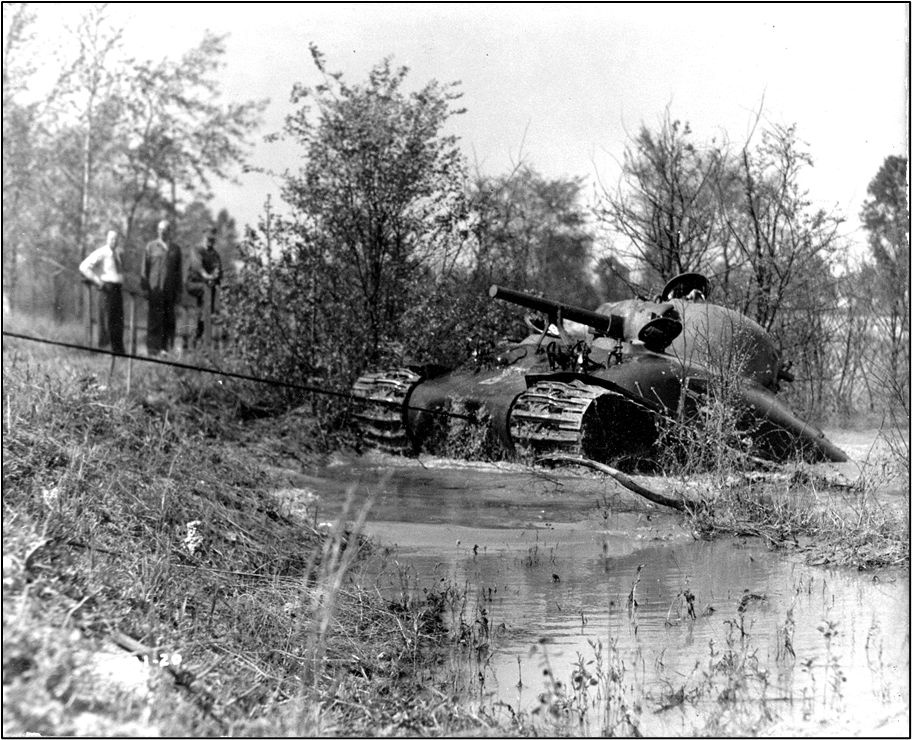

Above is a group shot of the tank test drivers, taken on February 2, 1945. Tanks are meant to be all terrain vehicles, so not all the testing took place on this track—there was “off-road” testing, too. And, as you can see below, it didn’t always go to plan. I’m pretty sure that tank is supposed to drive out of the lake, not be towed!

To the right is a close-up of a tank with one of the 800,000 grousers that Chrysler also manufactured. A grouser is an extension added to the track or tread to provide more traction in mud and other adverse conditions.

Below is a close-up of the storage yard for the 4,000 Army trucks that Chrysler rebuilt.

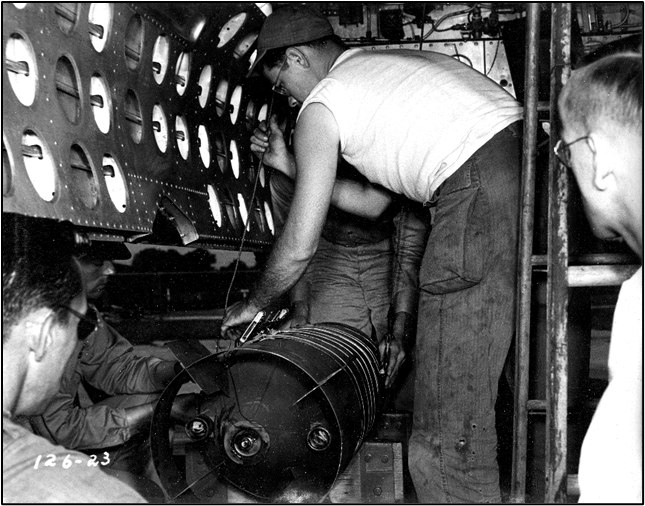

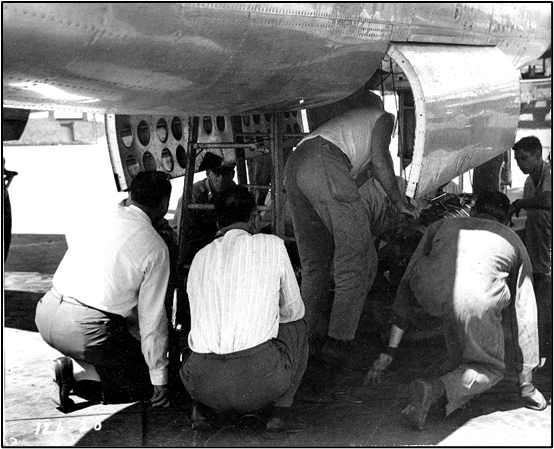

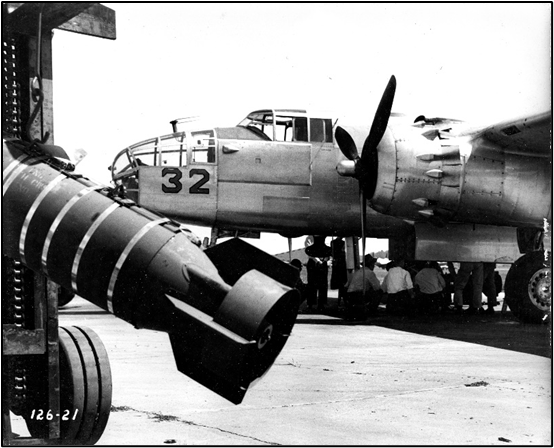

This plant also built cluster bombs. These photographs depict this type bomb being loaded onto a B-25 bomber.

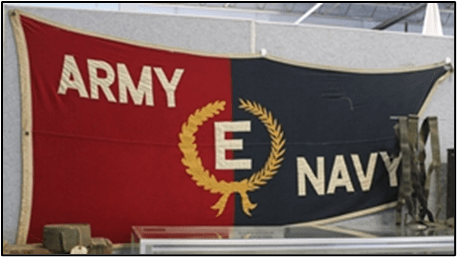

“In the early summer of 1943, the Evansville arsenal won the coveted Army-Navy “E” – Excellence – Pennant. In presenting it to the workers, Lt. Col. Miles Chatfield of the Army’s Ordnance Department said, “Ninety days after you broke ground, you proof-fired the first ammunition made at this plant. When the Chief of Ordnance asked you to switch from brass to steel you did the seemingly impossible and then when you were asked to convert some of your machines to .30 caliber carbine ammunition, you made the first cup within a week and two weeks later you proof-fired the first round of that ammunition. This all adds up to a remarkable accomplishment performed by those inexperienced in the ways of making ammunition, but with a willingness and devotion to patriotic duty second to none.””[i]

If you want to see more of the 924 photographs in the Raymond Frederick Diekmann Chrysler Wartime Collection, follow this link. To broaden your search, try the American Military History Gallery which contains photographs from other individuals and includes other American military conflicts in addition to WWII. There will be future blogs highlighting other contributions Evansville made to WWII—stay tuned!

Resources Consulted

Bigham, Darrel. Evansville : The World War II Years. Charleston, S.C. : Arcadia, c2005. General Collection F534.E9 B54 2005

MacLeod, James Lachlan. Evansville in World War II. Charleston, SC : History Press, 2015. General Collection F534.E9 M335 2015

McCutchan, Kenneth P. et al. Evansville at the Bend in the River: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, CA. : American Historical Press, c2004. General Collection F534.E9 M38 2004

Leave a comment