*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

Apologies for that groaner of a pun in the title!

In the first half of the 20th century, Evansville was a bit of a sleepy southern town, suffering, as did the rest of the country, from the lingering Depression. December 7, 1941 changed that dynamic completely as Evansvillians geared up for war. “Vanderburgh County firms would, by March 1944, receive more than $600 million in defense contracts, more than any southern Indiana county. One study in 1981 indicated that forty-eight Evansville businesses did some sort of war work.”[i] Let’s take a look at how the average citizen was impacted by and responded to these war contracts and the war itself.

Undoubtedly the largest impact was the huge influx of people coming into Evansville. In 1940 the city’s population was 97,062. Still dealing with the lingering effects of the Depression, the economy remained sluggish. After Pearl Harbor and the subsequent swift announcement that many defense contracts had been awarded to Evansville, this situation changed almost overnight. “The combination of increased industry from existing companies and production from new plants significantly raised the number of jobs — and in turn employees. Evansville’s total industrial employment from 34 major corporations jumped from 13,492 in 1941 to 78,775 in 1943. Chrysler increased from 650 to 12,700 employees and Republic and the shipyard from zero to 8,300 and 19,200 respectively.”[ii] Other companies with defense contracts or otherwise contributing to the war effort included Servel, Hoosier Cardinal, Sunbeam Electric Manufacturing Company, George Koch Sons, Mesker Steel, Mead Johnson, Shane Manufacturing, Bootz Manufacturing, and Bucyrus-Erie. Many of these likely needed additional employees, too.

What in the world to do with all these new people—not only the workers, but also their families? “The great influx of workers from the hinterlands put a severe strain on housing. Any garage, attic, or building with walls and a roof was sought for living quarters. Many of the old mansions along First and Second streets that had fallen into disrepair during the Depression were remodeled, and almost every one of their large, old rooms was turned into an efficiency apartment. Special war housing projects were quickly erected such as Gatewood Gardens, Diamond Villa, Columbia Apartments, and Parkholm.”[iii] Below is a Karl Kae Knecht cartoon from the Evansville Courier, March 5, 1942, which addresses the issue. Knecht was a cartoonist for the newspaper from 1906-1960. He was famous for his little elephant, Kay, appearing in his cartoons—take a look at the bottom right corner to see how Kay is going to help with the housing crisis.

One of the first housing projects to be built was the Armory Apartments near the old National Guard Armory on Rotherwood Ave., near the University of Evansville. These buildings are no longer standing. Seen next are the Fulton Square Apartments under construction, on W. Dresden St. There were almost 200 units, and this housing complex is still occupied.

Below are two views of Gatewood Gardens housing project on E. Maryland St. and Kerth Ave. It was completely vacated in 1959 and razed March 1960.

Some housing was considerably less “nice” than this. John A. Koch, housing director for the Evansville Shipyard, said, “There aren’t enough homes for the workers coming to Evansville, and trailers are the logical solution. It has been the solution in other cities with big war contracts. We will have to provide these trailer homes, and until it is possible to bring the trailer parking lots and camps up to the high standard of the county ordinance, we are going to have to be lenient in enforcing these unimportant details.”[iv] That unimportant detail? Flush toilets. (Some trailer park residents found their accommodations the best ever and thought the county health officer was too picky.) In the end, there were 16 licensed trailer parks in the city, including one at Pleasure Park and another on Diamond Ave. There were also plenty of unregulated, unlicensed places like “Trailer City,” which saw a tragic fire December 24, 1943 that killed two children. The following three photographs are from the Evansville Museum, courtesy of EVPL Digital Archive: Evansville in WWII. Each of these trailers was photographed December 27, 1943. Their specific locations are not identified.

Lyman Hall, radio commentator on WGBF radio, said,

The launching of five ships in four days at the local shipyard is worthy of note and subject for congratulation. It seems that no workers in industry are so worthy to hold their chins up along side the boys at the fighting fronts. We owe them something. The least we could do would be to give them better breaks on the housing situation. It is disheartening to the Navy officials and shipyard management to have trained workers leave town to rejoin their families, because after months of searching they find no quarters in Evansville to which they can move their families.[v]

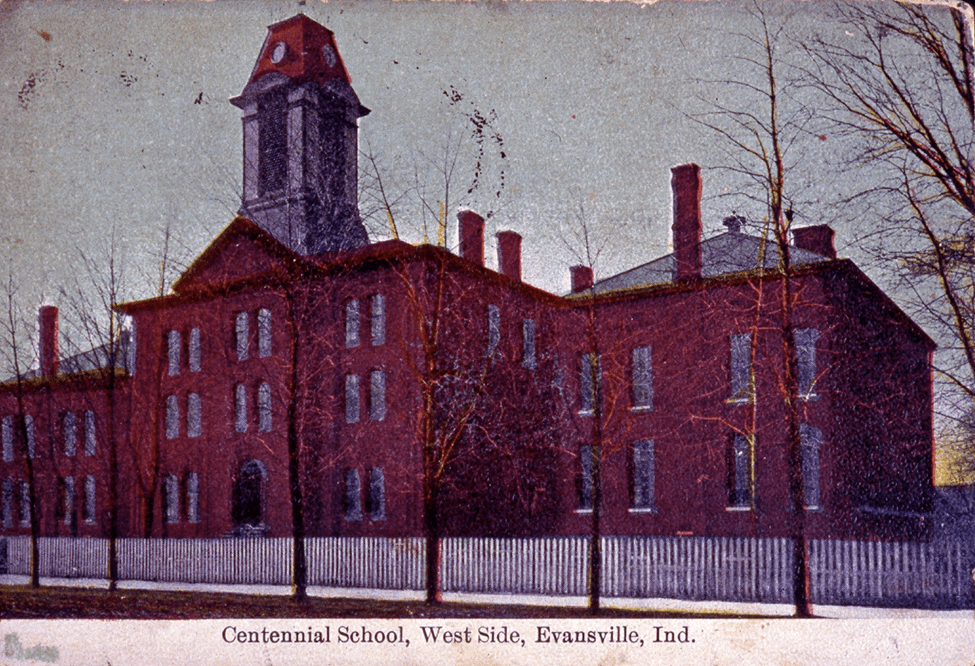

What about those workers’ children–where were they going to school? Townships squabbled with the city over who was responsible for schooling these children. Schools were overwhelmed by sheer numbers. In one instance, “Vogel, the nearest school within the township, was so overcrowded that Oak Hill Club nearby had been “taken over as an auxiliary.” The two nearest city schools, Howard Roosa and Henry Reis, were already at capacity, so the federal project children would have to go to Columbia School by bus if they were to come to city schools.”[vi] And if this wasn’t enough, there were not enough buses to transport the extra students, nor funding for school meals. Federal funding finally came through in December. School play centers were available for children 6-15 when school was not in session, for a fee of $.50/week, with $1.00/week additional for a hot lunch. The first was at Howard Roosa, with Culver, Third Ave. Colored School, and Lincoln Colored School soon joining, along with Baker and Centennial Schools. “Thanks to the Lanham Act it was possible to have nursery schools in Evansville which provided food for some 700 grade school children and afforded great assistance to parents working in defense plants.”[vii]

St. Vincent’s Day Nursery at 611 N. First Ave. was another source of day care for children with parents working in defense plants. This building and organization still exist in 2021.

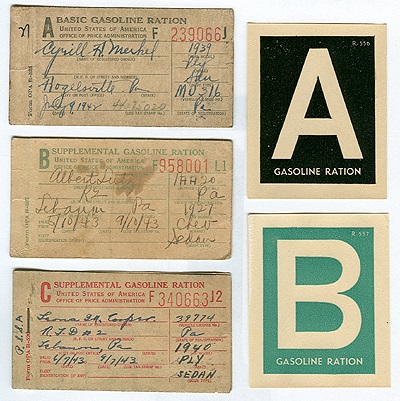

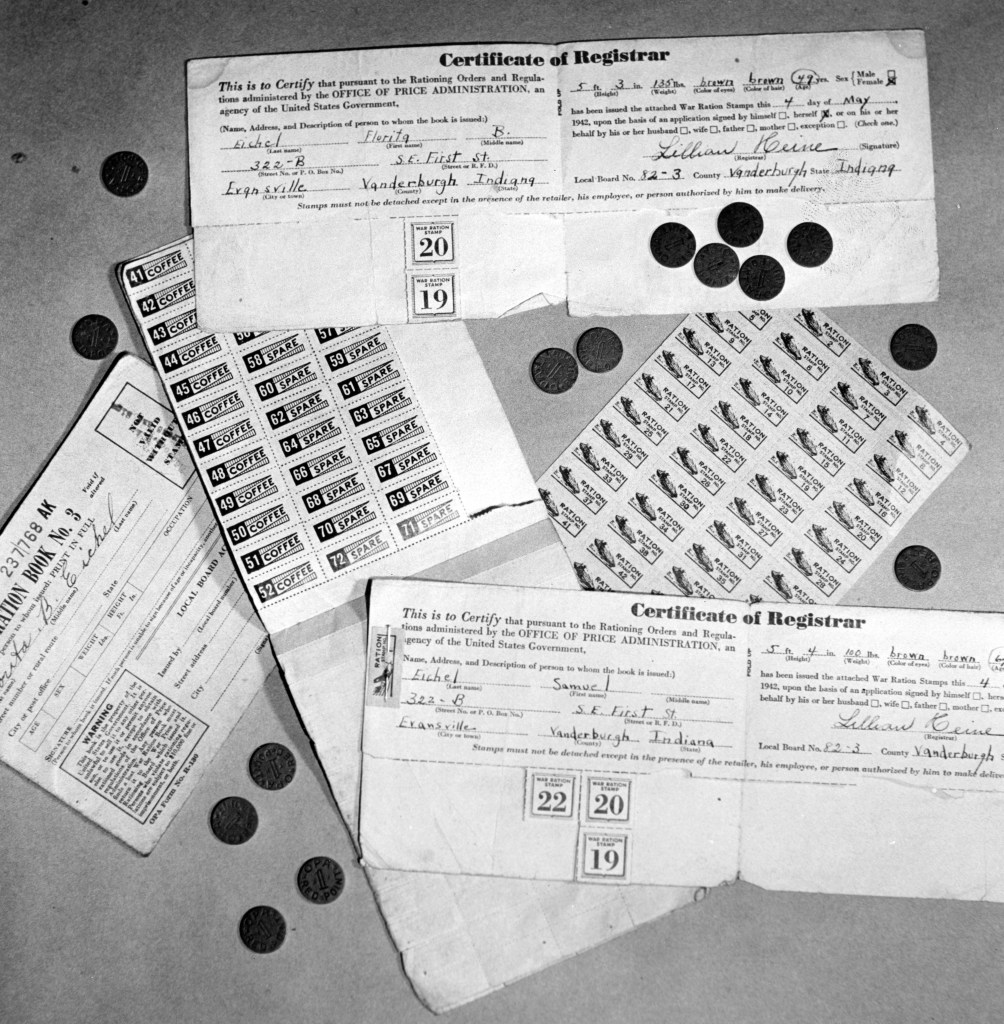

Transportation for workers was also a challenge. Even if a person owned a car (and many did not), gasoline was rationed. Shipyard workers, and probably others, were known to car-pool or share rides, which allowed drivers to stockpile their gasoline rations for recreational activities. The shipyard even had a transportation department which

assisted employees in all ration problems, and received and processed applications for gasoline, tires, automobiles, bicycles, and safety shoes. Applicants were required to know the average mileage covered each day or week in driving back and forth to work…. One “A” stamp was to be used every week, regardless of how many supplement stamps had been issued. The “A” books were good for eight weeks, with one coupon good for each week. … The “A” book allowed the owner 180 miles of driving per month, based on 15 miles per gallon. Of this amount, 60 miles must be used each month for driving back and forth to work. … The supplemental or occupational mileage, up to 460 miles a month, was covered by the “B” book, and from 461 miles up, the driver was entitled to a “C” book.[viii]

This photo shows the work of the shipyard’s transportation department, here performing a tire inspection.

UASC MSS 290, the Harold Morgan Collection

Although not specifically dealing with rationing, this WWII poster speaks to the need to use everything wisely.

These Karl K. Knecht cartoons from the Evansville Courier point out that not everyone was on board about war-induced shortages. All images are from the Evansville Museum via the EVPL Digital Archive: Karl K. Knecht Collection

Scrap metal drives promoted the very real need to recycle and reuse. These two images are of the same scrap metal drive in 1944, conducted on a lot behind the old post office (the Romanesque style building) at 100 NW 2nd St. Both are from the Thomas Mueller Collection.

This African-American man is high atop a huge pile of scrap metal in 1941.

These young men are cutting the bottoms off large metal cans and then compressing them to be used for scrap metal, circa 1945.

Despite any ideals of the time about a woman’s place being in the home, the fact that so many men were in the military meant that there was a very real need for women to take their jobs.

Indiana…received a much larger than average share of war contracts, ranking eighth in the nation, and its manufacturing industry grew more rapidly than that of most states. In 1944, payrolls of war industries accounted for nearly one-third of all Indiana income payments, ranking the state fourth nationally…. Women made up a significant proportion of those payrolls. In 1940, women represented 18 percent of those employed in manufacturing in the state. By the end of 1943, more than one-third of all factory workers in Indiana were women. The greatest increase in female employment in the state occurred in the defense industries, not only in machinery plants (mostly converted auto and electrical goods plants), where women on average made up one-third of the labor force, but also in iron and steel mills, where the number of women employed increased 260 percent by 1944. In some factories, such as a tank armor plant in Gary, an RCA factory in Bloomington, and most of the ordnance plants, women constituted the majority of workers. … Nearly 3,000 women, constituting one-sixth of the workforce, were employed in production jobs at the peak of wartime employment at the Evansville shipyard alone.[ix]

The image of Rosie the riveter is very well known, but this is certainly not the only role for women in industry. At the Evansville shipyard, no Rosies (or Rosses, for that matter) were used as all joining was done by welding. Mrs. Evelyn Cox, seen to the left, was the shipyard’s first female welder. She was quoted as saying that “my job isn’t nearly as tiring as doing a day’s ironing.” Nor was she alone. The five women below are three-position welders at the shipyard. This means that they were qualified to weld “as on a table top, or up or down as on a wall and the most difficult position of welding overhead as on the ceiling. This was a coveted status and difficult to achieve.”[x]

None of this necessarily meant equal work for equal pay, however. “Workers tended to argue that if a man had ever performed a job, it was, ipso facto, a “male” job, and women now employed in it should receive the higher “male” rate negotiated before conversion. But employers feminized disputed operations and accorded them the lower “female” rate, claiming that the process of conversion had simplified the tasks once assigned to men, making them more like those done by women before the war. Both sides were somewhat disingenuous since neither would admit the flimsy and esoteric basis for many prewar differentials. It became, however, increasing difficult to distinguish between operations performed by men and women.”[xi] In many instances, women were expected to give up these jobs when the war was over and men who did or could perform them returned home.

If the demand for employees failed to promote male/female equity, it was worse for racial equality. This was an era of segregation; “separate but equal” was the law of the land. White workers had no issue with African-Americans filling menial positions, but resisted strongly the concept of giving them skilled labor jobs. “Black men who sought specialized training to equip them for skilled jobs at, for instance, the shipyard, were denied access to training at the segregated Mechanic Arts School and had to make do with night courses offered at Lincoln High School. … Republic [Aviation] employed just nine blacks by the summer of 1945—six in maintenance and three as truck drivers.”[xii] The woman below performed janitorial work at the shipyard and the men were consigned to be waiters. Even the company picnics were segregated—whites picnicked and danced at Burdette Park, blacks at Stockwell Woods.

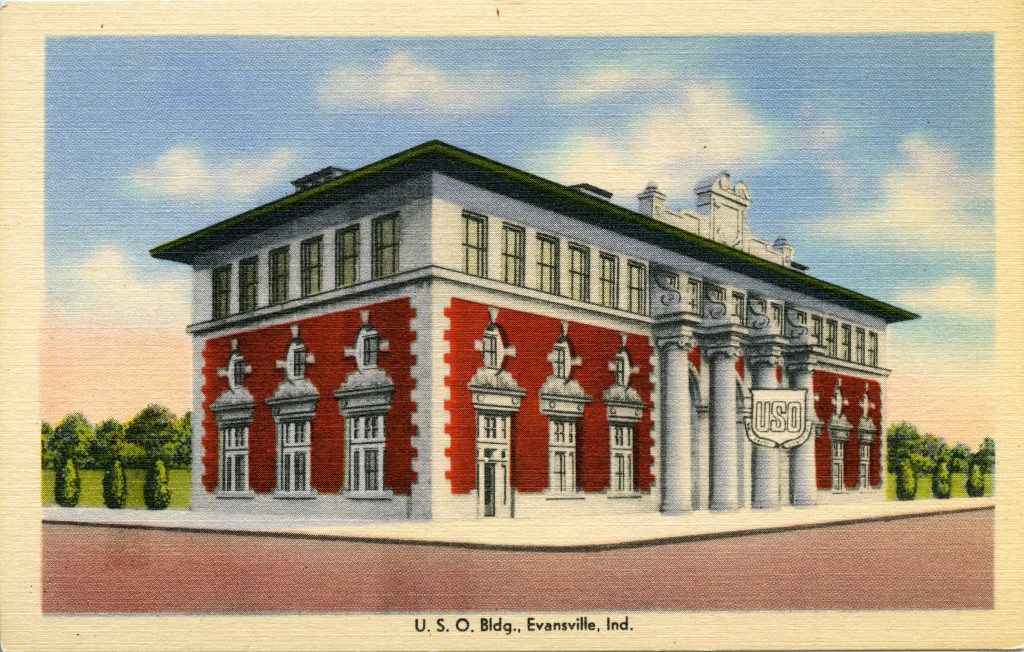

Even the USO was segregated. USOs provide entertainment, support, and assistance to soldiers and their families. White servicemen and their families enjoyed the USO at the old Central and Eastern Illinois Railroad depot on SE 8th St. (below, left). This building has been razed, but the columns were saved and now constitute the Four Freedoms monument on the riverfront. African-American soldiers and their families were served by the Lincoln USO (below, right), located in the former county orphanage on Lincoln Ave. at Morton Ave. It, too, has since been razed.

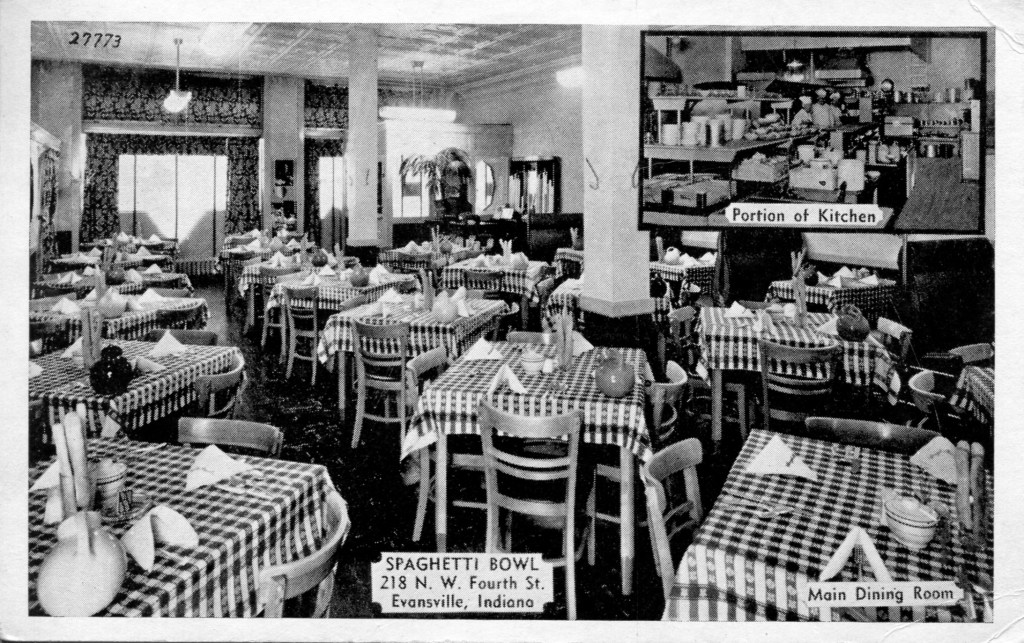

Local history buff Harold Morgan cited two rays of hope in terms of integration. One was the Spaghetti Bowl restaurant that served everyone and even offered a free meal to any serviceman or woman whenever it was open.[xiii]

Evansville was famous for its Red Cross Canteen on Fulton Ave., another place soldiers didn’t face racial segregation. In its three years in operation, it served 1,612,000 service men and women, an average of 1,280 meals per day. All was free—no serviceman or woman paid anything for food or assistance at Evansville’s Canteen.

All costs were provided for by the area citizens and the American Red Cross. All Canteen workers were volunteers, they numbered in the hundreds and for many this was their full time job. …The usual mode of transportation was by railroad. America had about 11,000,000 men and women under arms. An inductee would ride to training base by rail; go home for leave by rail. Then perhaps to a special training camp, home again and then to a permanent duty station, all via the railroads. … It appears that the army and navy put the men on a train and provided water and toilets and nothing else. There may have been no dining provisions for them along the tracks. Some canteens charged for food. … At any one time, there would have been many thousands of troops in the rail system. Evansville averaged 1,500 men and women per day during 1943 when more than 500,000 persons stopped for a meal, a drink and a chance to stretch their legs. The Canteen received a constant flow of food, service and money contributions from a radius of about 50 miles around Evansville. The towns in Illinois, Kentucky and Indiana took the Canteen on as their responsibility; they kept it very well supplied with what they could offer.[xiv]

I hope you’ve enjoyed this series of blogs about how Evansville both contributed to the war effort and was in turn influenced by these efforts. Stay tuned for more blogs on different topics, always highlighting materials within the UASC collections.

Resources Consulted

Bigham, Darrel. Evansville: The World War II Years. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia, c2005. General Collection F534.E9 B54 2007

Bone, Dona. Home Front Heroes: How Women & Children Helped Win WWII. Evansville, M.T. Publishing Co., 2019

Gourley, Harold E. Shipyard Work Force: World’s Champion LST Builders on the Beautiful Ohio. Mt. Vernon, IN: Wiedrich Publishing, 2000. 2 copies: General Collection, UASC Regional History VM301.E92 G68 2000

The Home-Front War : World War II and American Society. Edited by Kenneth Paul O’Brien and Lynn Hudson Parsons. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1995. General Collection D769 .H66 1995

Indiana City/Town Census Counts, 1900 to 2010. STATSIndiana

Lutgring, Trista et al. “Holding Down the Home Front.” Evansville Living Magazine, n.d.

MacLeod, James Lachlan. Evansville in World War II. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2015. General Collection F534.E9 M335 2015

McCutchan, Kenneth P. et al. Evansville at the Bend in the River: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, CA: American Historical Press, c2004. General Collection F534.E9 M38 2004

Morgan, Harold B. Home Front Heroes: Evansville and the Tri-State in WWII. Evansville: M.T. Publishing, 2007 UASC Regional Collection F534.E9 M58 2007

Morgan, Harold B. Home Town History: The Evansville, Indiana Area; A Photo Timeline. Mt. Vernon, IN: H.B. Morgan, 2009. UASC Regional Collection F534.E9 M67 2009

Morgan, Harold. “The Red Cross Canteen: 1942-1945.” Evansville Boneyard website.

[i] Bigham, p. 51.

[ii] Lutgring

[iii] McCutchan, p. 91.

[iv] MacLeod, p. 86.

[1] Gourley, p. 56.

[v] MacLeod, p. 93-94.

[vi] Gourley, p. 57-58.

[vii] Gourley, p. 55.

[ix] Home-Front War, p. 108-109.

[x] Morgan/Home-Front, p. 204.

[xi] Home-Front War, p. 111.

[xii] MacLeod, p. 69.

Leave a comment