*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian, and Isaac Kebortz, UASC student worker

You’ve surely heard someone use this phrase, which in general means that everything is included, but the expression originated with gunsmithing, and refers to the three major components of a firearm. University Archives/Special Collections (UASC) has a Kentucky/Pennsylvania style rifle, dated to the mid 1800s and is attributed to gunsmith Charles Flowers, who lived in Harmony, PA. We’re going to examine the component parts, consider the artistry involved, and briefly address the challenges of authentication. Let’s start with a small amount of history and then move on to a description of the rifle.

Rifles like this were common in the 18th and early 19th centuries. “Originally made in Pennsylvania, the longrifle played a crucial role in early settlement, and some people argue that it was a significant factor in the formation of the national character. Part tool, part weapon, sometimes status symbol, it was a unique New World creation growing out of European technology and the demands of the American frontier… The longrifle reflected the determination of a transitory people for whom the securing of land was a daunting imperative.”1 The fact that it is also known as a Kentucky rifle reflects the importance of its use by those explored the wilderness that in 1792 became the 15th state to be admitted to the Union, our first state west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Using the image below, let’s examine this rifle part by part. Technically, the stock of the gun is the wood and the barrel is the (more functional) metal that is supported by it. First, the patchbox, seen in the images below.

The patchbox is used to hold weapon accessories or cleaning materials. This one is fairly elaborate, with the hinged portion opens by depressing the button on the top edge near the back (just barely visible here). One common cleaning material was tow, a fiber made of used rope that was used to scour the barrel clean. This gun would have used black powder, a substance that does not burn entirely; over time this leads to sludge in the barrel called fouling. If not kept clean, in time the barrel would become so fouled that it was impossible to insert the ball. The name patchbox comes from the piece of lubricated wadding, or patch cloth, used to wrap around the ball. Generally the ball is smaller than the diameter of the barrel, and the patch takes up the extra space so the fit is snug. This snug fit allows the ball to engage better with the cut grooves, called rifling, within the barrel.

Next is the trigger, in this case, two triggers. The one in the back is used to set the trigger, and the forward one fires the gun. Setting the trigger lessens the amount of strength needed to fire the trigger; if it takes less strength to pull the trigger, then it’s easier to be more precise in your aim. That mechanism on top is called the hammer (aka the cock or the dog on older versions). Once the user has loaded the rifle (more about this later), this is pulled back, i.e., cocked, and then the trigger is ready to be pulled.

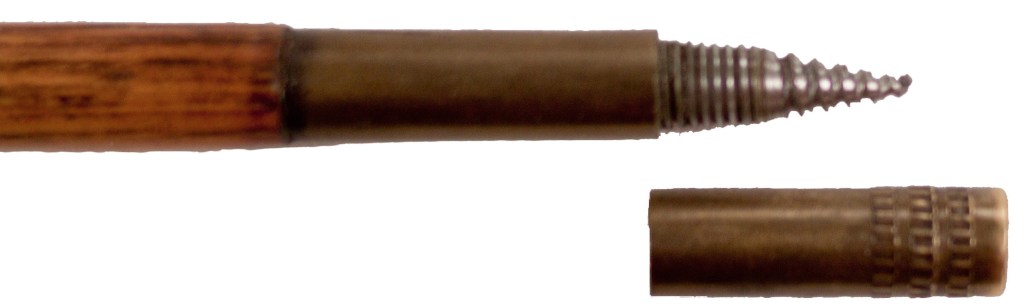

The final item of interest visible on this side of the rifle is the ramrod–that wooden rod with a metal end sticking out just below the barrel. The ramrod would be pulled out and inserted into the barrel to push the ball until it is fully seated against the powder. This rifle has a special feature in the metal tip of the ramrod which unscrews to reveal a ball screw, puller, or worm (seen in the second image above) that can be used to remove stuck ammunition. This would have been an expensive feature.

Here’s a full view of this side of the rifle.

Let’s move on to the other side of this weapon. We’ve covered the functional parts of the rifle, so this side displays decorative parts.

As you can see, this section is the back side of the lock mechanism.

There are three decorative items here, the Hunters’ Star, the acorn, and the weeping heart. Having three such decorations is indicative of Charles Flowers; only one is really needed to hold the screw in place and keep it from digging into the wood. In this case the functional shape is the acorn, an American symbol common in the early 19th century, and associated with small game like squirrels that ate acorns. On the left is the Hunters’ Star. This rifle has two of these…this one and the one on the cheek rest (where the gun should be pressed to the cheek when firing; seen in first image above). This image is typical of those used by 18th century German immigrants, although it goes back to older European hunting lore. It’s common to have a Hunters’ Star on the check rest. The final shape is the weeping heart: 1/2 heart, 1/2 teardrop. This image was popular with Native Americans, but could also be found on weapons of English or Scottish origin.

The final decorative item below is the 1888 Liberty Seated dime near the end. This type of dime was minted from 1837-1891.

There’s an 1854 Liberty Seated dime below the trigger guard on the underside of the gun. These may or may not have been added by Flowers as it was common for the rifle owner to customize his weapon by himself in this fashion.

And here’s the full view of this side.

Now that we’ve examined the parts of this rifle, how was it fired? First, the powder was measured and poured into the barrel. How much powder was determined by the shooter, depending upon distance to target and/or type of target. The ball was then inserted into the barrel, using/not using a patch or wadding. The ramrod was next used to assure that the ball was completely in place. The hammer could be half cocked at this time; this was the safety position, meaning that the rifle could not yet be released by the trigger. It was safe to carry the rifle in this position, and it was ready to be fire quickly with the addition of the percussion cap. These percussion caps did not come with this rifle, but they are similar to what would have been used with it.

After placing this cap on the cone, the hammer would be pulled into full cock and ready to fire, as seen below. When fired, the hammer would strike the percussion cap, which is filled with a chemical compound called a fulminate. This makes the firearm’s action more reliable than previous designs of locks, creating an explosion that would more consistently ignite the powder and fire the ball.

Although we are accustomed to seeing the rifle seated against the shooter’s shoulder, it originally would have been placed against the bicep. This fact accounts for the highly curved butt plate on the end of the stock.

The authentication that accompanied this rifle attributes it to Charles Flowers, a gunsmith that lived in Harmony, PA. Listen to this brief video by Rick Rosenberger, curator of the Harmony Museum as he talks about Flowers, rifles of this type, and Flowers rifles owned by the museum.

Tracking down more information about Charles Flowers presents a challenge! The information received with the rifle has a photocopied page containing some information about Flowers from The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle by Henry J. Kauffman. It says he was born in 1802, worked at the Arsenal in Pittsburgh during the Civil War, possibly learning his trade there, purchased a plot of land in Harmony, PA in 1866, and had his gunsmith shop on Wood St. The video states that he moved into this area in the 1840s, was listed in the 1850 Census as a coal miner but in subsequent censuses was listed as a gunsmith, and died in 1897. The 1850 Census entry with Flowers as a miner was corroborated as were the later censuses listing his occupation as a gunsmith. Most of the Census entries only provide an estimated birth date….some say 1815, 1818, or 1821. There is a Find a Grave entry for a Charles Flowers giving his birth date as February 22, 1821 and his death date as October 28, 1897. The information provided regarding his wife and daughter corresponds with the information on some of the Census entries. The Find a Grave entry is for a Flowers who was a Civil War veteran, serving with Company C of the 5 Pa. Heavy Artillery. Given that Find a Grave is a crowd-sourced database, it cannot be seen as completely reliable. What could be verified was that there was indeed a Charles Flowers, with the rank of private, in Company C with the same enlistment and mustering out dates.ii What about the Arsenal in Pittsburgh….finding information on this also provided challenging. No such specifically named entity was located, although there was an Allegheny Arsenal, founded in 1814, that was located in Lawrenceville, PA (which later became a part of Pittsburgh). It suffered a catastrophic accident when one building, known as the Laboratory, exploded on September 17, 1862. Are these two entities one and the same?

Another authentication challenges comes with the attribution of the rifle to Flowers, who was known to have signed or at least initialed his work on top of the barrel; this rifle bears neither. Flowers used locks made by the Goulcher family. (See image of a Goulcher lock below.)

Flowers was said to have been a master craftsman, and while parts of this rifle show this skill, others do not. How can this be explained? Perhaps some of the work is his, and other parts were done by a later owner, one with less skill. If this was an early work of Flowers, the imperfections might mirror the work of a man perfecting his craft, not yet the master he would become. One imperfection is the fact that the toe plate is not perfectly flush with the butt plate–but perfect alignment here is notoriously hard to achieve, a fact that might indeed argue for a rifle early in Flowers’ portfolio.

Researching this blog was a fascinating journey into an area of knowledge in which I had absolutely no background. I am indebted to UASC student workers Isaac Kebortz and Bill Smith, both of whom have the background that I lack. They very thoroughly and patiently explained this rifle to me, step by step, and equally patiently answered my MANY questions. Both have read this blog posting to ascertain that no errors based on my misunderstanding are included. Isaac also photographed the rifle in detail and provided many of the images seen here. If you enjoyed this blog, that is due in large part to the contributions of Isaac and Bill….thanks, guys! It is a joy to work with such committed and interested student workers that demonstrate the value of their USI education. Stay tuned for more explorations into the many treasures of University Archives and Special Collections.

Notes

1 Conaway, p. 98

ii Pennsylvania…/Bates

Resources Consulted

Conaway, James. “Renaissance of the Longrifle.” Smithsonian, v. 31:no. 5, August 2000, p. 96-103.

Kauffman, Henry J. The Pennsylvania-Kentucky Rifle. New York, Bonanza Books, 1960.

NRA National Firearms Museum website. A Prospering New Republic–1780 to 1860.

Leave a comment