*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

Do you recognize this woman? Unless you’re an art historian, I’m going to guess that the answer is no. (Not fair if you read the caption on this image first!) When you delve a little deeper, you find out that hers is an amazing story.

Rachel Ruysch (RAHG-kehl RAH-eesh) was born in 1664 in The Hague, the Netherlands. She was one of 12 children born to Frederik Ruysch and Maria Post. “Her mother, Maria Post, came from a creative family—her father was the Dutch imperial architect Pieter Post, and her uncle, Frans Post, was a leading landscape painter. Ruysch’s own father, Frederik, brought the scientific chops to her gene pool. A well-known physician and botanist, he served as Amsterdam’s praelector (or college officer) of anatomy beginning in 1667, and subsequently took positions as a professor of botany and supervisor of the city’s botanical garden. His reigning achievement, though, was his famed cabinet of anatomical and botanical curiosities: a five-room collection of embalmed and wax-injected organs, animals, plants, and countless other oddities which he posed in artful, macabre dioramas (in one, a baby’s hand holds a turtle egg as it hatches).” Theirs was a well off family who moved to Amsterdam and lived in an area with many other artists.

At the age of 15 Rachel’s father agreed that she would serve as an apprentice to artist Willem van Aelst. She worked with him until his death four years later, and learned valuable lessons both about painting and about arranging the flowers she painted so that they appeared more natural. “By the age of eighteen, Ruysch was already making a name (and living) for herself while rubbing shoulders with the city’s most popular flower painters and horticulturists.” It would be impressive today for someone of just-out-of-high-school age to already have renown–just consider how even more impressive it was for a young woman in the late 1600s. She even maintained her maiden name after her marriage because she was already successful at that time. “In 1693, Ruysch married the successful portrait painter …Juriaen Pool. The couple would go on to have ten children. Despite being more than occupied with her domestic situation (and even if the family’s status suggested they were very likely to have had hired domestic help), Ruysch continued to paint, producing over 250 paintings over seven decades.Her painting career brought in steady income for the family, with Ruysch earning, on average, more per painting during her lifetime than even Rembrandt.”. Another source says, “Her work nevertheless commanded hefty sums, known to sell for as much as 1,200 guilders for a single canvas. By means of comparison, “Rembrandt never got really more than 500 guilders for a painting,” as National Gallery curatorial fellow Nina Cahill has explained.” A document entitled Money in the 17th century Netherlands puts this into modern terms: 100 guilders in the 1600s was comparable to $6000 US dollars (in 2016, the date of this document).

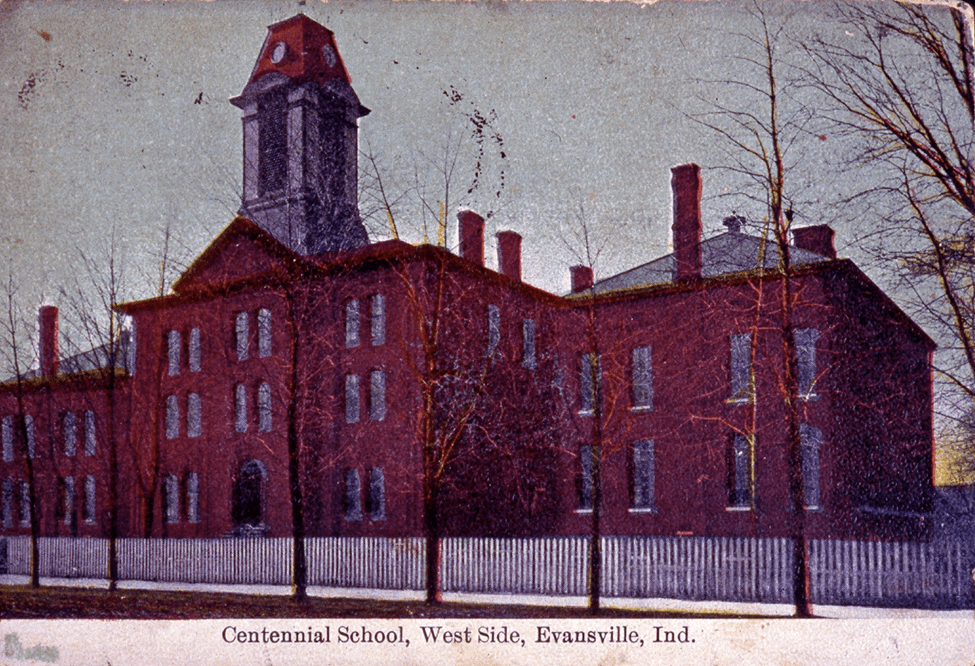

Above is the postcard image (MSS 010-644) that first caught my attention. (The actual postcard image is quite dark, so for the sake of clarity, this image was found here.)

Rachel Ruysch was the first female painter to be accepted into the painters guild in The Hague. In 1706 she gained the patronage of Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine of Bavaria, serving as court painter until his death in 1716. During this time she gave birth to her last child (she was 47 at the time!), naming him Jan Willem to honor her patron, who agreed to serve as the child’s godfather. There is some conjecture that she was so well respected that she was not required to move to Dusseldorf, site of the court, but rather permitted to stay in Amsterdam. Others state that she and her family did indeed live in Dusseldorf from 1708-1716. She accepted commissions from other wealthy patrons, including Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Husband Juriaen Pool was commissioned to paint her portrait, finishing it just as the Elector died.

Rachel continued to paint the rest of her long life, proudly including her age of 83 on a canvas toward the end of her career. She died October 12, 1750. Germaine Greer says, “As the creator of pictures of perfect beauty she was heaped with commissions and honours, but her poise never altered. She never succumbed to flattery and demand, but continued to work as fastidiously as ever.” (Greer, p. 242) Ann Sutherland Harris further states, “She nearly always includes some fruit–dusky plums, a split pomegranate, a fuzzy peach–and always some insects, especially beetles, butterflies, grasshoppers, and dragonflies. The perfection of these specimens, which are seldom available in ideal condition in the same season, reminds us that Ruysch’s realism is in fact an ideal representation. She is in effect following the doctrine that it was the artist’s duty to select from nature and to portray perfectly what nature could only render imperfectly. Above all, the study of her work testifies to her profound knowledge of contemporary botany and zoology. Her works are an extraordinary synthesis of seventeenth-century scientific interest in the range and variety of species found in nature and the artistic traditions she used to display them. The results are beautiful visions of impossible natural perfection.” (Harris, p. 160)

Enjoy more of her beautiful work!

Resources Consulted

Greer, Germaine. The obstacle race: the fortunes of women painters and their work. New York : Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1979. General Collection ND38 .G73 1979

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Women artists, 1550-1950. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: distributed by Random House, 1976. General Collection N6350 .H35

Money in the 17th century Netherlands.

“Rachel Ruysch.” The Art Story.org.

“Rachel Ruysch.” Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts. Robinson, Lynn. “Rachel Ruysch, Flower Still-Life. Smarthistory, August 8, 2015.

These YouTube videos are worth your time:

Ruysch: Painter of the court and mother of 10 | National Gallery (YouTube)

Leave a comment