*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

Have you ever heard this expression? It means you were almost, but not quite, successful in something you attempted. “Its origins were back in the 1920s when carnivals would hand out cigars as prizes. These games were obviously targeted at adults and not children. Carnival games were very difficult to win and the stand owner would simply shout the phrase when the player miserably failed to win. Hence no cigar as a reward. With time, carnivals began to move and travel around the USA and so did the saying. Nowadays stuffed animals have replaced cigars as prizes but not the phrase.”1

Full disclosure: this blog is not about carnival games and prizes, but rather about a cigar factory that operated in Evansville, Indiana for some 114 years. The origins of this story go back to 1833, when six members of the Fendrich family (mother, father, four sons: Joseph, Charles, Francis, and Herrmann) immigrated to the United States and settled in Baltimore, MD. They came from southwestern Germany (then the Holy Roman Empire), from the Baden area. The family soon grew with the addition of a fifth son, John. Sometime in the 1840s the four oldest sons decided that the cigar and tobacco business would be a good fit for them and so apprenticed themselves to members of that trade around Baltimore. Their motivation for entering this field is unknown, although the area of Germany from whence they came was known for cigar making. Probably more relevant is the fact that during the 1830s Cuban cigars gained in popularity, and the United States began to produce better quality tobacco. It seemed to be a lucrative trade to enter, with Baltimore one of the top cigar centers in the country.

By 1850 all five brothers felt confident enough to open their own factory, at 155 Forrest Ave. in Baltimore. Their main product was plug tobacco, which came from Kentucky. (Plug tobacco is chewing tobacco, densely compressed into a square.) They also opened a production factory in Columbia, Pennsylvania. It is clear that the Fendrichs were successful; only five years later they moved their operations to Evansville. This put them not only nearer to the Kentucky source of their tobacco, but also in an excellent location to take advantage of river transportation down to New Orleans and out to the wider world.

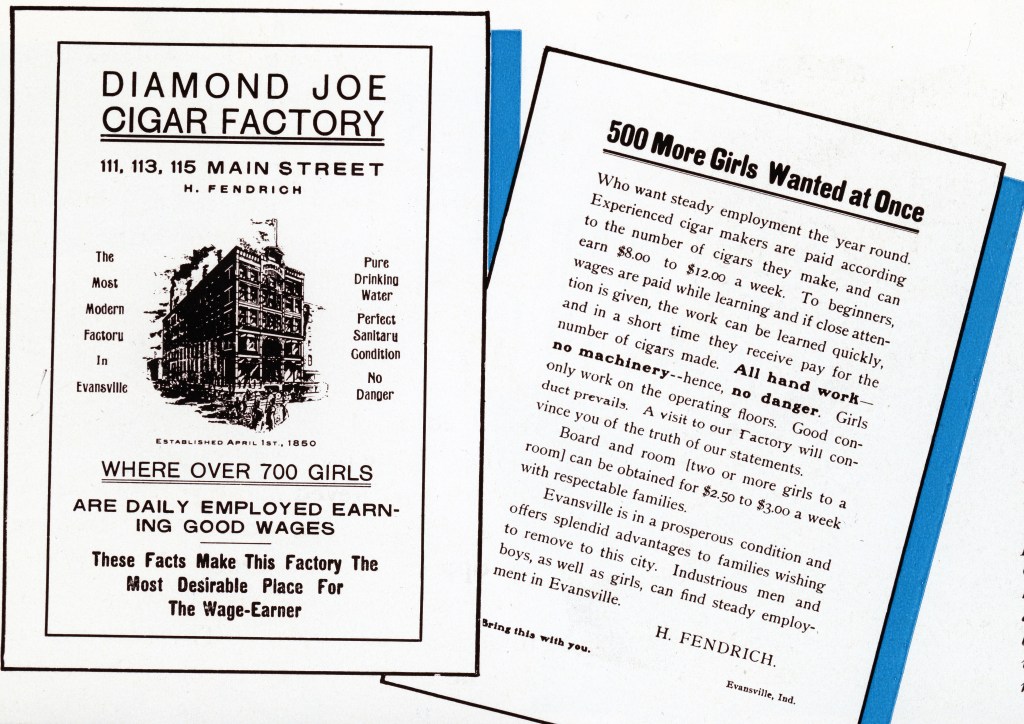

Above is what is believed to be the first location of the Fendrich cigar enterprise in Evansville. It later moved its store and factory up a block on Main Street, to a five story building, seen below.

The original company name was Francis Fendrich and Brothers. At some time in the 1880s the oldest three brothers retired, leaving the company to the second youngest Fendrich brother, Herrmann. The company name became Herrmann Fendrich, successor to Fendrich Brothers. Herrmann died in 1889 and then name again changed, now H. Fendrich. His only son, John Herrmann Fendrich, took up the reins of the business at this point.

The company flourished, with warehouses opening in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Wisconsin, in addition to those in Evansville. Having grown up in the business, John knew it intimately. He maintained quality standards and improved processes by developing and patenting “new techniques for removing harsh irritants in tobaccos to make his cigars milder and mellower, and to give them a most inviting bouquet to smokers.”ii Multiple sources speak of his “aggressive salesmanship.” In 1889 Fendrich only employed 40 cigar workers, but under John’s leadership it grew to employ 3,000 cigar makers. According to Hyman, Fendrich grew to become the largest of Indiana’s over 600 factories, and 100,000 cigars were produced daily. The company history also stresses the growth in the production of custom-made cigars and labels. Hyman counters with: “Cigar factories that created dozens of “custom” brands generally kept their tried and true blends constant, changing only the name and label to suit the customer. Sellers desiring a “house” or “custom” brand selected a particular manufacturer (out of 10,000+ available) because they like the taste and appearance of their cigars, and usually wanted few, if any, changes. Minor changes like wrapper color, dipping the cigar’s head in a sweetening agent or spraying the blend with various flavorings made for the easiest changes. Fendrich’s profusion of brands were most likely a combination of custom blends for some, minor tinkering like described above for other customers and packing their standard brands under a custom label for yet others. How many of the brands and labels were actually created by the H. Fendrich company itself not recorded.”iii

While the exact number of custom blends is unclear, the growth in production was enough to warrant the move to the larger facility on Main Street. One very important factor was Fendrich’s employment of women. This was quite a departure from the norm…..women in that time period did NOT work in factories. Take a look at this advertisement seeking female employees.

The early 1900s reader of this would have likely had an entirely different response than today’s reader. I’m just going to leave this as it is, a document reflecting its time period. However, I will note that while it may have been considered progressive at the time to hire women, it’s also true that it “was a smart business move, cutting salary and production costs while doubling output.”iv

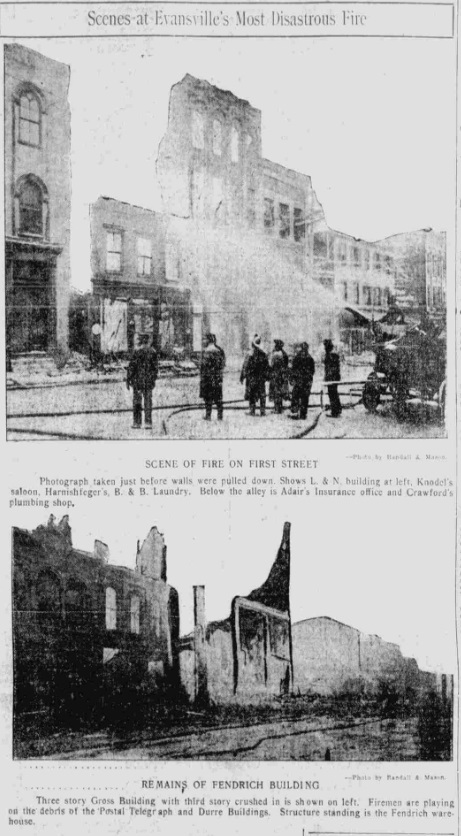

Disaster struck on December 6, 1910, when a massive fire completely destroyed the factory, taking with it ten nearby businesses and one private residence. The fire was at night, so no employees were killed, but equipment and stock suffered a total loss. The December 7, 1910 Evansville Courier reported that the fire was thought to have started with a gas leak. “Chief Grant and Assistant Chief Wilder believe such must have been the cause from the rapid spread of the flames in the Fendrich building. … New gas pipes were laid in the building Monday. They were attached to an old pipe that had not been used for fifteen or twenty years. At 5 o’clock in the afternoon, the pipes were tested and found to be in good order. It is the theory of Mr. Fendrich that after all the lights had been turned off, the old gas pipe sprang a leak from the increased pressure and gradually filled the building.”v The newspaper detailed $594,750 in total losses, $457,000 of which was the cigar factory, the Fendrich building, warehouse stock, and insurance on the stock. Many workers arrived to work that morning, completely unaware of what had happened. Famous Courier cartoonist Karl K. Knecht showed their dismay.

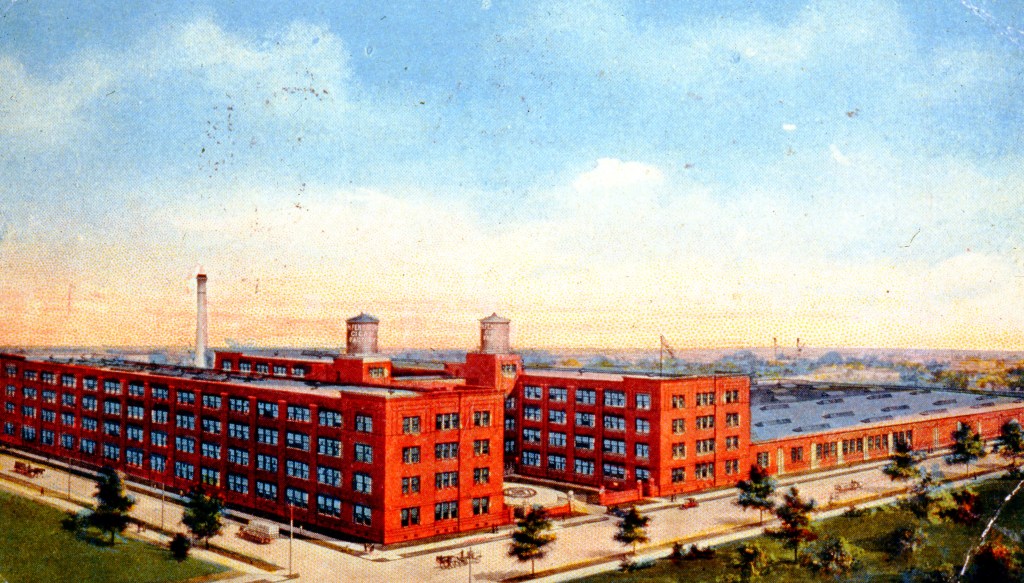

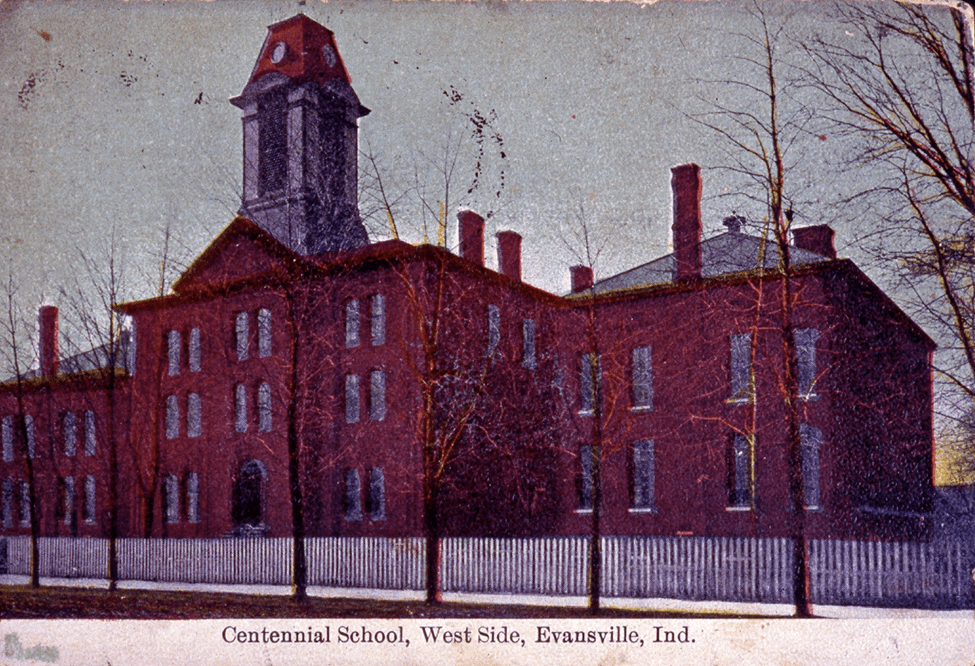

John Fendrich, however, was not deterred. “The company bought the eastern half of Willard Park from the Trustees of Willard Library and built a large modern facility on Oakley Street between Pennsylvania and Illinois.”vi The new factory opened in 1912, with “wings adjacent to open court yards in front and back, maximizing natural light for rollers and packers, and allowing for an adjoining symmetrical series of warehouses under one roof, with all the latest equipment and design. The 192,000 square structure included a cafeteria, first aid, showers and a recreation area.”vii If you are familiar with Evansville, this location is where Berry Plastics is today.

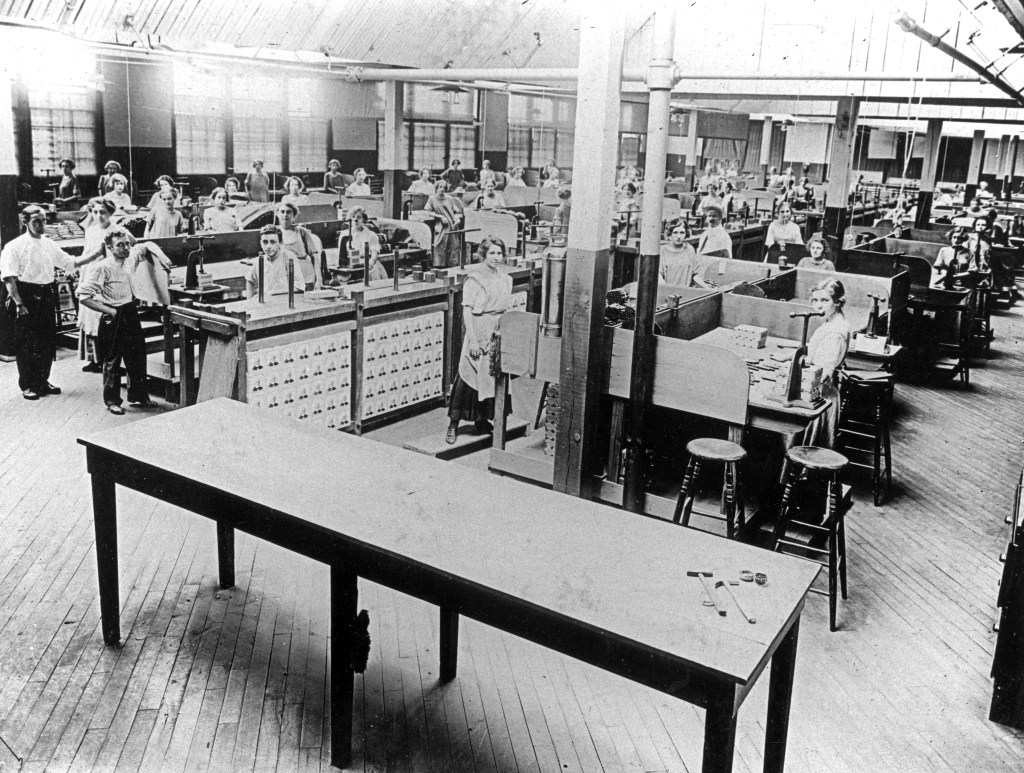

The company moved forward, changing with the times as necessary. “In the 1880s when work was done under gas lights, a three-girl team using wooden molds turned out 1,000 cigars a day. In the new factory, once machines were installed, four girls working one machine turned out 4,400 perfect cigars each ten-hour shift. In keeping with the times white and “colored” cigar makers worked in separate buildings.”viii

Packaging cigars at the Fendrich Cigar Factory at 101 Oakley St., circa 1912. UASC MSS 216-007, the Maxine G. Akins Collection

Like other businesses in Evansville, H. Fendrich contributed to the war efforts in both WWI and WWII.

During World War II, Fendrich continued to provide cigars for the troops. “Tens of millions of Fendrich-made cigars, approximately 30% of production, were packed in special wooden cases with waterproof liners designed for dropping during bad weather or for floating ashore to troops on remote Pacific islands with no harbor facilities.”ix The company received this citation from the War Department in February 1945: “We know that our soldiers appreciate the convenience of obtaining a good cigar when they want it….your cooperation in maintaining all-out production will continue to bolster the morale of American troops overseas.”x Furthermore, the factory’s machine shop manufactured precision parts for local war industries.

Fendrich celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1950, but this was its last big “hurrah.” In November 1967 the company was sold to the Parodi Cigar Corporation, which soon moved its production to its Pennsylvania facility. March 4, 1969 was the last day a Fendrich cigar was made in Evansville.

Enjoy these images of Fendrich cigar factory workers.

Male and female employees at the Fendrich Cigar Factory at 101 Oakley St., circa 1912. UASC MSS MSS 216-008, the Maxine G. Akins Collection

Footnotes

1Heredia

ii One Hundred Years…

iiiHyman

ivHyman

vEvansville Courier

viMcCutchan, p. 58

viiHyman

viiiHyman

ixHyman

x One Hundred Years…

Resources Consulted

Evansville Courier, Wednesday, December 7, 1910, p. 1 and 3.

Heredia, Marianna. “What do “close, but no cigar” & 3 other sayings mean? Cigar Country website.

McCutchan, Kenneth P., William E. Bartelt, and Thomas R. Lonnberg. Evansville at the Bend in the River: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, CA: American Historical Press, 2004. UASC Regional Collection F534.E9 M38 2004

One Hundred Years of Cigar Making 1850-1950. Evansville, IN: H. Fendrich, Inc. (booklet in the Anna Orr Collection in UASC, MSS 205-1-2.

Leave a comment