*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

Every blog I write contains at least one item from a UASC collection. Sometimes an item just sparks my imagination and I’m off on a voyage of discovery. This is one such blog.

While looking at MSS 010, a miscellaneous collection of nearly 1000 postcards, I ran across this.

Now take a look at the message on the back of this postcard.

A man named Adolph sent this to his sister in Evansville. He got to see the Hindenburg at Lakewood, NJ and said, “I’d like to take a ride on it.” This postcard was mailed on August 10, 1936. History tells us that the Hindenburg crashed in a fiery disaster at that location on May 6, 1937, less than one year later. Adolph’s timing was fortunate….he got to see the Hindenburg in all her glory, and while I cannot know if he ever got his wish to take a ride on her, I can say that there was no one in the list of those killed named Adolph!

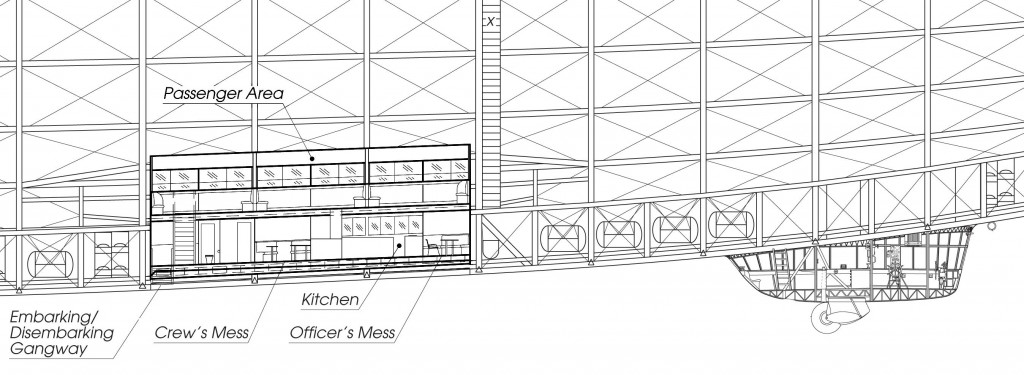

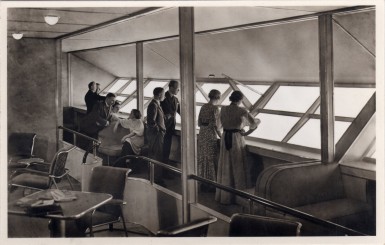

The Hindenburg was the latest in luxury travel. It was huge, some 3 times longer than a 747. While an Atlantic crossing took 5 days on an ocean liner, this airship made it in only 2.5 days. Passengers were accommodated on 2 decks. “Hindenburg’s “A Deck” contained the ship’s Dining Room, Lounge, Writing Room, Port and Starboard Promenades, and 25 double-berth inside cabins. The passenger accommodations were decorated in [a] clean, modern design …, and in a major improvement over the unheated Graf Zeppelin, passenger areas on Hindenburg were heated, using forced-air warmed by water from the cooling systems of the forward engines. Hindenburg’s Dining Room occupied the entire length of the port side of A Deck. It measured approximately 47 feet in length by 13 feet in width, and was decorated with paintings on silk wallpaper. … The tables and chairs were designed … using lightweight tubular aluminum, with the chairs upholstered in red.” (quote here)

“On the starboard side of A Deck were the Passenger Lounge and Writing Room. The Lounge was approximately 34 feet in length, and was decorated with a mural …depicting the routes and ships of the explorers Ferdinand Magellan, Captain Cook, Vasco de Gama, and Christopher Columbus, the transatlantic crossing of LZ-126 (USS Los Angeles), the Round-the-World flight and South American crossings of LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin, and the North Atlantic tracks of the great German ocean liners Bremen and Europa. … During the 1936 season the Lounge contained a 356-pound Bluthner baby grand piano, made of Duralumin and covered with yellow pigskin. The piano was removed before the 1937 season and was not aboard Hindenburg during its last flight.” (quote here)

“Hindenburg was originally built with 25 double-berthed cabins at the center of A Deck, accommodating 50 passengers. After the ship’s inaugural 1936 season, 9 more cabins were added to B Deck, accommodating an additional 20 passengers. The A Deck cabins were small, but were comparable to railroad sleeper compartments of the day. The cabins measured approximately 78″ x 66″, and the walls and doors were made of a thin layer of lightweight foam covered by fabric. Cabins were decorated in one of three color schemes — either light blue, grey, or beige — and each A Deck cabin had one lower berth which was fixed in place, and one upper berth which could be folded against the wall during the day. Each cabin had call buttons to summon a steward or stewardess, a small fold-down desk, a wash basin made of lightweight white plastic with taps for hot and cold running water, and a small closet covered with a curtain in which a limited number of suits or dresses could be hung. … None of the cabins had toilet facilities; male and female toilets were available on B Deck below, as was a single shower, which provided a weak stream of water “more like that from a seltzer bottle” than a showe …. Because the A Deck cabins were located in the center of the ship they had no windows, which was a feature missed by passengers who had traveled on Graf Zeppelin and had enjoyed the view of the passing scenery from their berths.” (quote here) B Deck cabins were slightly larger and had windows.

The B Deck also held the ship’s kitchen, passenger toilet and shower facilities, the crew and officers’ mess, a smoking room and a bar. A smoking room aboard a ship powered by hydrogen? For safety’s sake it “was kept at higher than ambient pressure, so that no leaking hydrogen could enter the room, and the smoking room and its associated bar were separated from the rest of the ship by a double-door airlock. One electric lighter was provided, as no open flames were allowed aboard the ship.” (quote here)

Given this time period, it should come as no surprise that to the Germans, the Hindenburg was far more than just a fancy way to get from point A to point B. “Although the Hindenburg was in development before the Third Reich came to power, members of the Nazi regime viewed it as a symbol of German might. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels ordered the Hindenburg to make its first public flight in March 1936 as part of a joint 4,100-mile aerial tour of Germany with the Graf Zeppelin to rally support for a referendum ratifying the reoccupation of the Rhineland. For four days, the airships blared patriotic tunes and pro-Hitler announcements from specially mounted loudspeakers, and small parachutes with propaganda leaflets and swastika flags were dropped on German cities. … Later in 1936 the Hindenburg, sporting Olympic rings on its side and pulling a large Olympic flag behind it, played a starring role at the opening of the Summer Games in Berlin.” (quote here) The PBS NOVA documentary, Hindenburg: the New Evidence, says that the Germans had a goal of linking all the major cities of the globe, of connecting the world (which they believed would be a German world) by 1945.

Here’s how events transpired in May 1937. One important fact to know is that these airships had an issue with on-time arrival, and a big goal in 1937 was to improve this issue.

The ship left Frankfurt at at 7:16 a.m. on May 3, 1937. It carried 36 passengers with a crew of 61. Poor weather conditions across Europe and the Atlantic meant the Hindenburg was already 12 hours behind schedule when she arrived at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, NJ late in the afternoon of May 6. There were thunderstorms there and concern over these delayed the “touchdown” (really a docking) until after shortly after 7:00. As it approached, the captain and crew struggled to keep the ship trim….it seemed to be tail heavy. Some hydrogen was released, along with some water ballast, and finally some of the crew were asked to move forward into the nose, all to no avail. Possibly because they were already late, no one was sent to go back and see why the tail was still too heavy. SPOILER ALERT: they should have taken the time.

Finally, at 7:21 p.m., with the ship about 180 feet above the ground, two landing ropes were tossed down to the ground crew. Four minutes later the ship went up in flames.

“The fire spread so quickly — consuming the ship in less than a minute — that survival was largely a matter of where one happened to be located when the fire broke out. Passengers and crew members began jumping out the promenade windows to escape the burning ship, and most of the passengers and all of the crew who were in the public rooms on A Deck at the time of the fire — close to the promenade windows — did survive. Those who were deeper inside the ship, in the passenger cabins at the center of the decks or the crew spaces along the keel, generally died in the fire. … As the ship settled to the ground, less than 30 seconds after the first flames were observed, those who had jumped from the burning craft scrambled for safety, as did members of the ground crew who had been positioned on the field below the ship. Natural instinct caused those on the ground to run from the burning wreck as fast as they could, but Chief Petty Officer Frederick J. “Bull” Tobin, a longtime airship veteran and an enlisted airship pilot who was in charge of the Navy landing party, cried out to his sailors: “Navy men, Stand fast!!” Bull Tobin had survived the crash of USS Shenandoah, and he was not about to abandon those in peril on an airship, even if it meant his own life. And his sailors agreed. Films of the disaster (seen in image immediately above) clearly show sailors turning and running back toward the burning ship to rescue survivors. Hindenburg left Frankfurt with 97 souls onboard; 62 survived the crash at Lakehurst, although many suffered serious injuries. Thirteen of the 36 passengers, and twenty-two of the 61 crew, died as a result of the crash, along with one member of the civilian landing party.” (quote here)

Hindenburg Captain Max Pruss immediately claimed sabotage. Ernst Lehmann had previously commanded the Hindenburg but was aboard this flight strictly as an observer, was badly injured and died of his injuries the next day. “Before dying, Lehmann told American airship officer and Lakehurst commander Charles Rosendahl that he believed Hindenburg must have been destroyed by an “infernal machine” (Hollenmaschine), presumably referring to a bomb or other sabotage device, or possibly a shot fired from the ground.” (quote here)

Why did the Germans use hydrogen, known to be very flammable? Why not use helium, which would also lift the ship but is not flammable. The thing is, Hindenburg’s designer wanted to use helium. “However, the United States, which had a monopoly on the world supply of helium and feared that other countries might use the gas for military purposes, banned its export, and the Hindenburg was reengineered. After the Hindenburg disaster, American public opinion favored the export of helium to Germany for its next great zeppelin, the LZ 130, and the law was amended to allow helium export for nonmilitary use. After the German annexation of Austria in 1938, however, Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes refused to ink the final contract.” (quote here)

The Secretary of Commerce, who had jurisdiction “relating to the investigation of accidents in civil air navigation in the United States, …[was charged] to investigate the facts, conditions and circumstances of the accident involving the airship Hindenburg, which occurred on May 6, 1937, at the Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey, and to make a report thereon. … [The conclusion was that] the cause of the accident was the ignition of a mixture of free hydrogen and air. Based upon the evidence, a leak at or in the vicinity of cell 4 and 5 caused a combustible mixture of hydrogen and air to form in the upper stern part of the ship in considerable quantity; the first appearance of an open flame was on the top of the ship and a relatively short distance forward of the upper vertical fin. The theory that a brush discharge ignited such mixture appears most probable.” (Taken from the Air Commerce Bulletin of August 15, 1937 (vol. 9, no. 2) published by the United States Department of Commerce, and found here.)

At the time, insufficient evidence was gathered to truly determine the cause of the accident. Other than eyewitness reports, investigations were based on newsreels taken that day. The problem with this is that all the films were taken from the same location, facing the ship, and only began after the fire broke out. Since the fire began in the back, there was no film footage of its ignition. Then, at the 75th anniversary commemoration of the disaster, an 8 mm film by spectator Harold Schenck was offered by his nephew to current day Hindenburg experts. His film was shot broadside and offers a new view of events. He had offered the film to the Commerce Dept. investigators at the time, but they believed the newsreels they had were sufficient.

PBS’ Nova program had an episode entitled “Hindenburg: The New Evidence” that originally aired May 19, 2021. First, the film and camera were vetted as authentic. A Caltech professor of chemical engineering, Dr. Konstantinos Giapis, conducted the investigation. All craft flying through the air build up an electric charge, but unless there is a pathway for this charge to flow, it’s not a problem. The Hindenburg fire started 4 minutes after the two landing ropes were dropped. Did they serve as this pathway? If so, why was there a 4 minute delay? Tests on rope very like that used were conducted and the ropes were proved to be conductive, and even more so when they were wet, as they were on that rainy day in 1937.

“Giapis agonized over how to explain that discrepancy…. [Finally], the answer came to him: After the ship was grounded, it became more electrically charged. Before the mooring ropes made connection with the ground, the Hindenburg collected a positive charge. However, this continued only to a point; indeed, as the skin became more positively charged, it also more strongly repelled any additional charge from collecting. Then, when the mooring ropes were dropped, electrons from Earth’s surface moved up to the frame, giving the ship a positively charged skin and a negatively charged frame. Just like how the north end of a bar magnet will be attracted to the south end of another bar magnet, that negatively charged frame began pulling more positive charge out of the stormy atmosphere and onto the ship’s skin. In other words, by grounding the frame with the mooring ropes, the landing crew had inadvertently made more “room” for positive charge to gather on the ship, setting the stage for the disaster. “When you ground the frame, you form a capacitor—one of the simplest electric devices for storing electricity—and that means you can accumulate more charge from the outside,” Giapis says. “I did some calculations and I found that it would take four minutes to charge a capacitor of this size!” With the ship now acting as a giant capacitor, it could store enough electrical energy to produce the powerful sparks required for igniting the hydrogen gas—which, based on eyewitness accounts, may have been leaking from the rear of the ship near its tail. This theory could also help explain a question that puzzled Giapis from the start: How did a spark occur in just the right spot to ignite leaking hydrogen? “Hydrogen was leaking at one specific location in this humongous thing. If there is a spark somewhere else on the ship, there is no way you would ignite a leak hundreds of feet away. Charge could move on wet skin over short distances but doing that from the front of the airship all the way to the back is more difficult,” he says. “So how did the spark find this leak?” Any place where a part of the frame was in close proximity to the skin would have formed a capacitor, and there were hundreds of these places all over the ship, Giapis says. “That means the giant capacitor was actually composed of multiple smaller capacitors, each capable of creating its own spark. So I believe there were multiple sparks happening all over the ship, including where the leak was,” he says.” (quote here)

Quite a story from one little postcard, isn’t it?!

Resources Consulted

Hindenburg Accident Report: U.S. Commerce Department. Airships.net

The Hindenburg Disaster. Airships.net

The Hindenburg’s Interior: Passenger Decks. Airships.net

Klein, Christopher. “The Hindenburg Disaster: 9 Surprising Facts. History.com, May 5, 2020.

“Newly released film of Hindenburg disaster. TheHistoryBlog

PBS NOVA. Hindenburg: The New Evidence. Episode aired May 19, 2021.

Taylor, Alan. “75 Years Since the Hindenburg Disaster. The Atlantic magazine, May 8, 2012.

Leave a comment