Introduction to History 246 Circus Project

The New Woman Under the American Big Top

By Tiffany Sandoval

During its Golden Age (roughly between the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries), the US circus mirrored the values, beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes of American society, but it also helped to shape it. By defying society’s expectations, the circus became a powerful platform for addressing social issues such as gender and its norms. For that reason, movements and changes in support of women gained strength during that time. So, while the circus reflected the prevailing societal attitudes towards women, it also highlighted the progress and persistent challenges they faced in the era. But let’s go back to the late 1800s and early 1900s to understand this better.

Throughout this period, white women were still subject to Victorian ideals of domesticity and femininity.[1] One would think there was no room in the circus for female performers. However, it was not true, as women played an essential role in the circus, especially as performers. Instead, media showed them in more domestic settings through “articles about the nomadic yet wholesome lifestyle of these women, focused on their domestic abilities and feminine sensibilities.”[2]

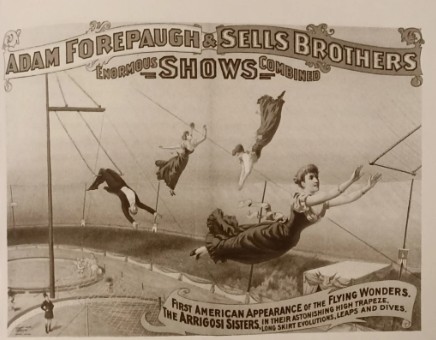

Gender norms were also reinforced by circus owners, who dictated a second set of rules for female workers to uphold their reputation and ensure they were publicly acceptable. For example, ballet girls in the Ringling Bros. Circus were not allowed to wear flashy outfits, had an 11 pm curfew, and were not allowed to stop at hotels.[3] White circus women were then portrayed, particularly outside their performances, as modest and delicate individuals who followed societal expectations. A lithograph from 1896 (see Figure 1) exemplifies these efforts by displaying performers in full gowns following the time’s dress code.

Figure 1.

Lithograph of the “The Arrigosi Sisters”, 1896.

Source: Janet Davis, The Circus Age: Culture & Society under the American Big Top (North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 109.

However, “the uniqueness of the circus world also offered a much different sent of social norms, boundaries, and expectations.”[4] This enabled “The New Woman” to be born. The term New Woman, was one of empowerment which was created and popularized in 1896 it continued to be applied to female performers a long time after its appearance.[5] With this term, several changes came along, especially in how the female performer was presented and perceived. They were no longer exclusively dainty; now, some showcased muscular bodies and impressive strength, wore full beards or reformed their dress code. Together, they celebrated female power, completely defying their contemporary gender norms.[6]

Circus proprietors, on their side, did not hesitate to capitalize on these events. They started marketing female workers in bolder ways as female nudity became a prominent phenomenon within circuses. For instance, some managers disguised the sexual striptease as family-friendly entertainment (although, it is essential to note that nudity within this context meant short-coverage attire or clothing like leotards, tights, or short-sleeved dresses above the knee).[7] This phenomenon can be appreciated in the cover of the 1947 King Bros Circus Magazine (see figure 2) where a female performer is advertised wearing a very revealing costume. As might be expected, the public did not receive this very well, as audiences and puritanical reformers looked down upon female performers.

Cover of King Bros 1947 Circus.

Source: Thomas J. Dunwoody Circus – MSS 326, University of Southern Indiana

To win over public opinion and mitigate the strong sexualized presence of the female circus performers, owners appealed to sentimental discourses of domesticity in media with narratives such as women never traveling alone and having the desire to get married.[8] In regards to this circus scholar Janet Davis states that “In the ring, the nearly nude female body was both sexually attractive and strong. Yet outside the ring, showmen classified these muscular bodies into normative categories”.[9] Paradoxically, this domesticated eroticism catapulted circus women to the center of advertisement campaigns, although, the number of campaigns was incongruent with their actual participation at the moment.[10]

Although female performers were once again subject to gender norms, the public slowly accepted the New Woman. This enabled causes like the suffrage movement to gain traction thanks to Big Top performers like Josie De Mott and Katie Sandwina, who actively and openly supported it not only through their jobs in the circus promoting gender equality but also by getting involved in feminist causes. [11] As a result, the presence of women in different societal spheres, like the workforce and political activism, increased, demonstrating the adaptable capacity that circuses and American society possess. This flexible approach allowed for women’s participation in society to grow and develop. Clearly, the Golden Age American circus participated in a paradoxical dynamic reflecting societal attitudes toward women. It also defied these perspectives while highlighting progress and challenges faced by its performers, specifically white females. This made the circus an essential platform for social change on issues such as gender and suffrage. As for white female performers faced contrasting portrayals that eventually brought change not only for them but for women outside the circus, too. Finally, it was American society’s openness to new ideas and changes that allowed it to accept and integrate these changes despite having a traditional and patriarchal view of women’s role in society.

[1] Janet Davis, The Circus Age: Culture & Society under the American Big Top (North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 83.

[2] Rebecca Reid, “Flirting and boisterous conduct prohibited”: Women’s work in Wisconsin circuses: 1890-1930 (Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin, 2010), 11.

[3] Micah Childress, Life beyond the Big Top: African American and Female Circus folk, 1860 – 1920 (England: University of Cambridge, 2016), 188.

[4] Andrea Ringer, Big Top Labor: Life and Labor in the Circus World (Tennessee: University of Memphis, 2018), 101.

[5] Ringer, 95.

[6] Davis, 82 – 83.

[7] Davis, 83 – 85.

[8] Davis, 86 – 93.

[9] Davis, 105.

[10] Davis, 116 and 93, respectively.

[11] Ringer, 96 – 97.

Leave a comment