*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian.

One of the many treasures in the UASC collections is a (true) story written by Thomas Horan on March 27, 1865, entitled “A Sketch of My 15 Months in the C.S.A. Prison.” In this blog, all italicized quotations are from Horan’s writing. The original spelling and grammar was maintained, with a correction in brackets only if necessary for clarity.

Horan lived on a rural portion of what is now North Green River Road in Vanderburgh County, Indiana. He served as a private in Company H, 65th Indiana Volunteers, enlisting on August 18, 1862, and seeing action in Kentucky and Tennessee. Late 1863 found his unit in the area of Knoxville/Morristown, Tennessee, where they took part on the Battle of Bean’s Station. “The Battle of Bean’s Station was a tactical victory for the Confederacy that accomplished little other than to add to the bloodshed and loss of life on both sides. Casualties are uncertain, but records suggest that the Union lost 700 soldiers (killed, wounded, captured/missing) and the Confederacy lost 900 soldiers. With [Confederate Lieutenant General James L.] Longstreet’s withdrawal into the mountains of eastern Tennessee, the battle of Bean’s Station marked the last engagement of his ill-fated Knoxville Campaign.”i

The Confederate army might have withdrawn but the war was not over, so Horan and several of his fellow soldiers were sent out as couriers to establish a Union line. All was well until the evening of January 24, 1864, when “a scouting party of Texas Rangers, being 20 in number, charged in on us by surprise and captured us after striping [stripping] us of every thing in our possession, nearly leaveing us naked. They marched us that night and the next day. In the eavening [evening] we arrived at Newmarket as hungery as wolvs [wolves], for they gave us nothing to eat on the march. Here we remained in prison until the morning of the 28[th], when we were taken out and marched to Morristown. There we were drove in to a pen like hogs and kept until the 2nd of Feb.”

The march continued into Virginia, where in Richmond they “were taken out and marched through the principle [principal] streets of the city to feast the eyes of the Southern Ladies on Yanks.” They were then taken across the James River to Bell Island. “Here we find a Retchard [wretched] place. Men die more or less every day with cold and hunger. Our rations per day are two spoons full of beans and a little piece of corn bread equal to a half pint of meal. Here we were turned on the Island destitute of blankets or shelter with but two sticks of cordwood to 20 men for 24 hours. I have had to take my shirt [to] wrap my feet to keep them from freezing. Men froze to death every night.”

There was some talk of prisoner exchange but Horan was not included, so the march continued until March 18 when he arrived at Andersonville Prison. He wrote, “If ever their was a hell on Earth its one. Here I was turned in the stockade without a blanket or a shoe to my foot and the skies above for my shelter and I remained in this condition untill the 13 of Sept.”

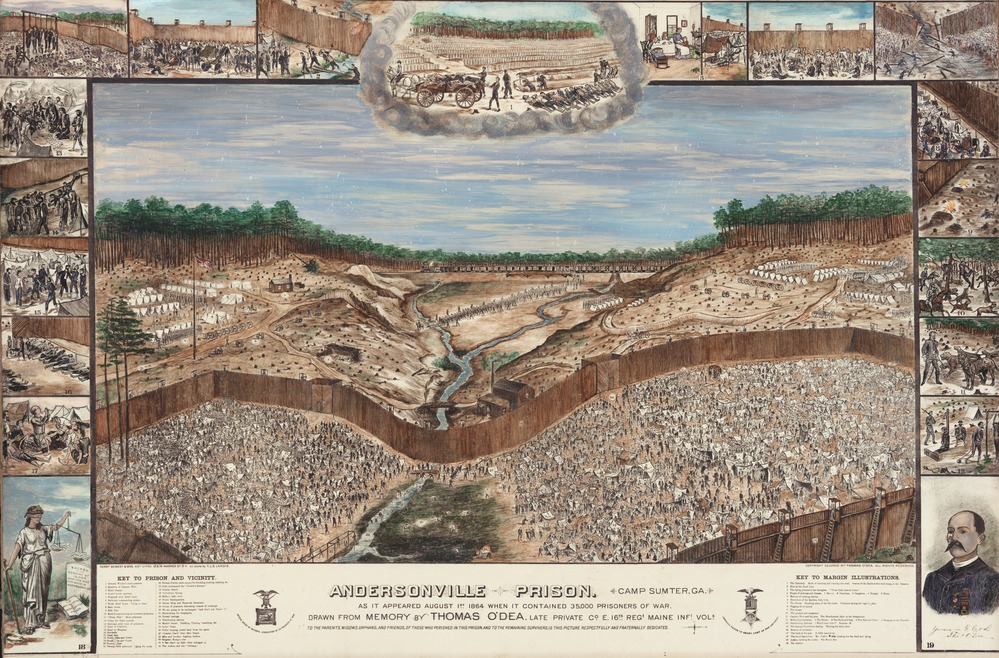

Horan’s assessment of Andersonville was accurate. Of the some 150 prison camps, both Union and Confererate, Andersonville had the highest mortality rate. There were 45,000 held there during its 14 months of operation (the planned capacity was 10,000), with 13,000 dying from the atrocious conditions. Its very location, chosen for its remoteness so as to lessen the threat of attack, made supplying basic necessities like food and shelter challenging. The water supply from the nearby creek was contaminated. Sergeant Samuel Corthell, Company C, 4th Massachusetts Cavalry, said, “The camp was covered with vermin all over. You could not sit down anywhere. You might go and pick the lice all off of you, and sit down for half a moment and get up and you would be covered with them. In between these two hills it was very swampy, all black mud, and where the filth was emptied it was alive; there was a regular buzz there all the time, and it was covered with large white maggots.”ii The image seen to the right was made by a map-maker for the Union who was imprisoned for a little over a year, 8 months of that time at Andersonville.

Horan tried hard to escape from Andersonville, making multiple attempts to tunnel out, but was unsuccessful. “Approximately 19 feet inside of the stockade [at Andersonville] was the “deadline,” which prisoners were not allowed to cross. If a prisoner stepped over the “deadline,” the guards in the “pigeon roosts,” which were roughly thirty yards apart were allowed to shoot them.”iii On September 13 Horan and others were told they were being sent to Savannah by train, and resolved to jump off the train and attempt to escape that way. Horan escaped from the train and wandered aimlessly and hungrily through the swamps for about two weeks before meeting up with some deserters from the 1st and 5th Georgia Cavalry. “They treated me so kind that I made up my mind to stay with them two or three days which I did to my own sorrow.” They turned him in and he was marched back to Savannah. “There they put me in a stockade but I was not there long before I turned groundhog and dug out. A half canteen and a wooden paddle was our tools to dig with. So off we started myself and a little Frenchman for our gunboats which were some 30 miles distance.” They made it as far as the coast, despite many travails related to not understanding how the rising and falling of the tide worked, and from feet lacerated by walking on oyster shells. They were unable to contact the Union gunboats, who shot at them, suspecting a trap. They were soon recaptured, tried once again to tunnel out, but were unsuccessful. There ensued much marching through the southern portion of Georgia, including more treks through the swamps. Once they reached Albany, Georgia, they were put on a train and returned to Andersonville, arriving on Christmas Eve.

By the 18th of March 1865 the tide of the war finally turned so that the Union forces liberated them from Andersonville. Horan says he weighed 175 pounds when he was first captured and upon his release, weighed 106. The former prisoners were taken to Camp Fisk near Vicksburg, Mississippi to await exchange/repatriation and a trip back home up the Mississippi River by steamboat. His story, written at Camp Fisk, ends with a note to his family saying how much he looks forward to seeing them.

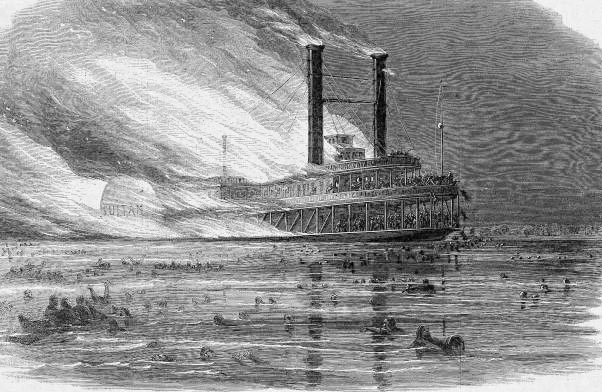

Horan’s trip back to Indiana was to be aboard the steamship Sultana, a sidewheeler built in 1863, captained at that time by James Cass Mason. As many as 5,000 former prisoners were headed to Vicksburg. “Steamboats were taking the men home and the US Government was paying so much per man, per hundred miles, to carry them home. [Chief Quartermaster Captain Reuben Benton Hatch] proposed to Mason that he could guarantee the Sultana got at least 1,000 men (worth about $2,500, or more than $40,000 today) if Captain Mason would give him a kickback.”iv Mason was eager to make such “easy” money, even allowing a leaky boiler to be patched instead of replaced as was recommended, in order that he not arrive too late and miss his chance. Both Hatch and Mason were well aware that the Sultana’s capacity was 376 passengers and up to 85 crew members, but when she left the dock on April 24, 1865 she carried 2,137 passengers: ex-prisoners, guards, crew members, and a small number of paying customers.

As the ship headed upriver, passing by people on shore, the soldiers tended to rush to the side and wave. Due at least in part to the overcrowding, this caused the ship to tilt alarmingly, so that the captain feared she might capsize. In addition, this shifting weight caused the water in the boilers to slosh back and forth, dangerously increasing the pressure in them. After stopping in Memphis, the Sultana started off again in the early morning hours of April 27, heading to its final stop in Cairo, Illinois.

“Around 2:00 a.m., when the Sultana was about seven miles north of Memphis, three of the four boilers suddenly exploded. The horrendous explosion came from the upper back part of the boilers and ripped upward through the heart of the Sultana. The blast went up at about a 45-degree angle, ripping apart the center of the main cabin, destroying the middle of the texas cabin (the section of the steamboat that includes the crew’s quarters), and shearing off the back two-thirds of the pilothouse. …With the loss of three…boilers, the towering smokestacks lost their support and toppled. …The left stack crashed heavily onto the center of the crowded hurricane deck, smashing it down onto the equally crowded second deck below them. Dozens and dozens of soldiers were crushed to death between the two decks. … As the debris from the wrecked upper decks slid down into the exposed fireboxes, the center of the Sultana slowly burst into flames.”v

Initially, the Sultana faced into the wind, meaning that the flames blew towards the stern. Those trapped in the bow seemed safe enough, until both of the sidewheels broke off, turning the boat completely around. Immediately those in the bow were in mortal danger.

The sinking of the Sultana was the worst maritime disaster in American history, even until today. Of the 2,137 people aboard, 1,169 died. Every child that was aboard perished. The number of Union soldiers lost (1,047) is higher than the losses on almost every Civil War battlefield. More people were lost from the Sultana than would be on the Titanic 47 years later. Captain Mason also lost his life. “In total, 786 people had to be rescued. … Most of those rescued were suffering from scalds and broken bones. Almost all were suffering from exhaustion and exposure in the frigid spring water. … Unfortunately, with the river at flood stage and running fast, most of the victims of the Sultana disaster were never recovered. Bodies were seen floating in the river days after the explosion, hundreds of miles downstream.”vi Private Thomas Horan had survived the horrors of Andersonville, but he was never seen again. There is a gravestone for him in the McCutchanville Cemetery, but no body is buried there. He was only 25 years old.

Here’s the strange thing…why don’t we know about such a catastrophic disaster? Well, timing is everything in news. President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, only 13 days prior to the explosion, and his body was being transported across the country in a funeral cortege. Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was hunted down and killed just the day before. The final Confederate Army surrender happened the day before, also. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was fleeing from Union cavalry. “Too many monumental events were taking place for people and big eastern newspapers to get excited over the sinking of a steamboat or the deaths of soldiers from western states.”vii

The Sultana herself sank and was lost deep below the muddy Mississippi. Over the years the river changed course, and eventually the remains were buried under a farm field in Arkansas, some 2 miles distant from the river. This final location was not found until 1982, and the ship remains there today.

Resources Consulted

“Andersonville Prison.” American Battlefield Trust website.

“Andersonville Prison.” New Georgia Encyclopedia online.

“The Disaster.” The Sultana Association of Descendants and Friends website.

“Sinking of the SS Sultana: Topics in Chronicling America.” Library of Congress Research Guides.

“The Sultana Disaster April 27, 1865.” American Battlefield Trust website.

Sultana Disaster Museum website.

Trudeau, Noah Andre. “Death on the River.” Naval History. August 2009 (v.23:no.4)

YouTube videos

Nightmarish Negligence: The Tragedy of The Steamboat Sultana. Brick Immortar podcast.

The Sinking of The Sultana: A Short Documentary. Fascinating Horror podcast.

Leave a comment