*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

How do you learn to bake a cake without actually going into a kitchen and making one? Reading a recipe just isn’t enough! How does a baby learn to walk without practicing? How do you learn to drive a car without actually getting behind the wheel? Clearly the answer is that you cannot (at least not well) without some hands-on knowledge.

So, how does a medical doctor learn about the human body, how it should work, how it looks when it doesn’t work correctly, and how to fix it, if s/he has never studied anatomy and physiology outside of a textbook? Today we are confident that a qualified physician has actually had real hands-on experience by having his/her hands inside the human body…but it wasn’t always the case.

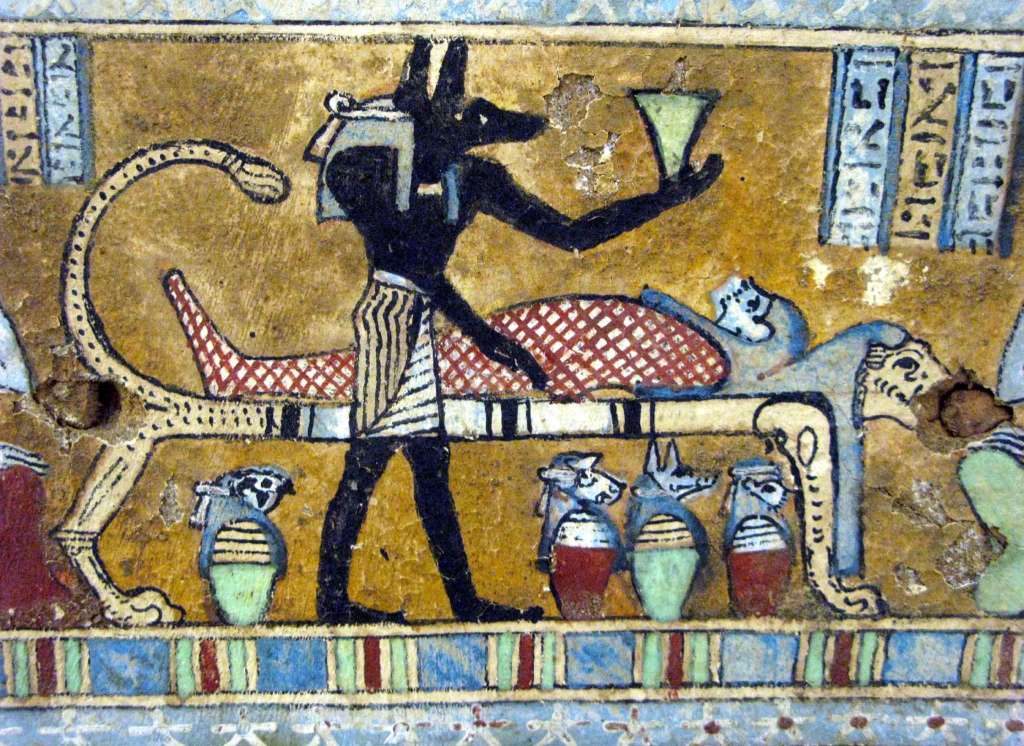

Ancient Egyptians learned a bit about the inside of the human body through embalming, but were leery of offending the gods…they found a “debased” man and hired him to make a big central incision and then run away. As he fled, they threw stones at him to prove to the gods that they (the embalmers) were properly displeased with his action. Many other cultures (Greeks, Middle Eastern peoples, the early Christian church, etc.) venerated the body and/or found a dead body to be unclean, thus making dissection an anathema. Fortunately, there was an early exception. “Herophilus, born in 335 BC, is recognized as the first person known to have performed and reported a systematic dissection of the human body. …Unfortunately, all of the written works of Herophilus are thought to have been lost in the fire that destroyed the fabled Library of Alexandra in 391 AD.”i

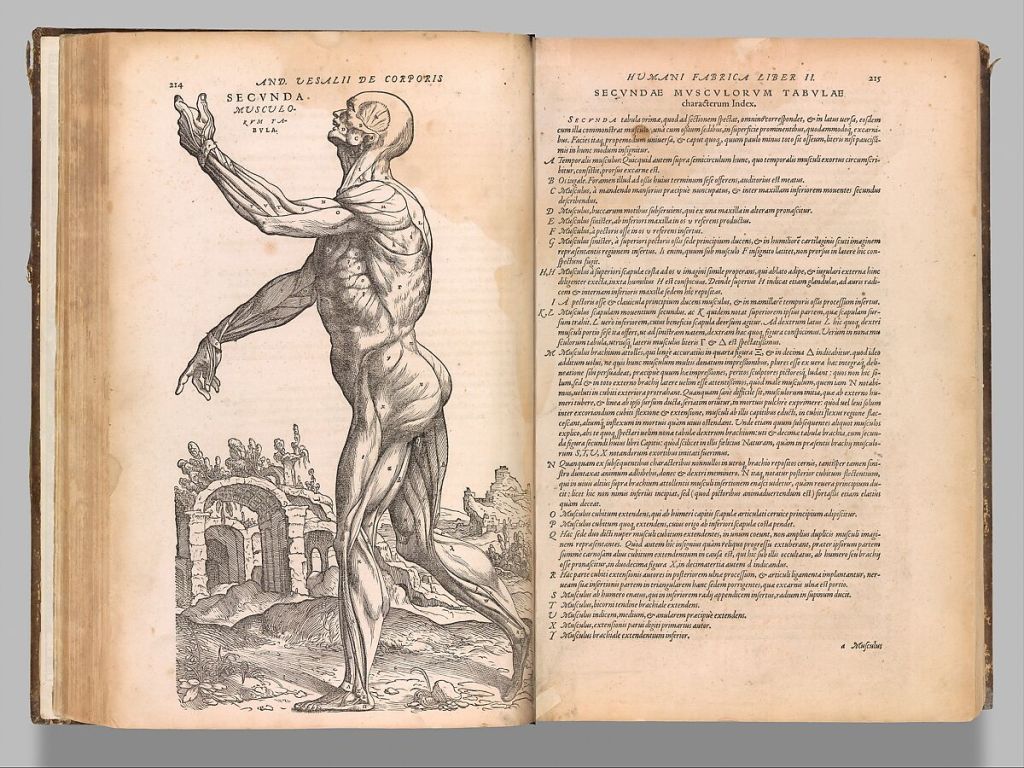

Thus followed a long period of belief that there was little value in studying anatomy, or that dissection would prevent salvation. Galen, on whose work early medicine relied, studied the anatomy of animals and made extrapolations (often incorrectly) about the human body. Progress was made in 1231 when Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II “decreed that a human body should be dissected for anatomic study at Salernum, in Italy, at least once in five years, and it was compulsory for the physicians and surgeons of the kingdom to attend.”ii Leonardo da Vinci is well known today for his anatomical drawings, but these were largely unpublished in his lifetime. Andreas Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Of the Structure of the Human Body) was published in 1543, the first printed anatomy book full of illustrations based on the human body, serving as a correction for many of Galen’s incorrect assumptions. Thus was the study of human anatomy reborn.

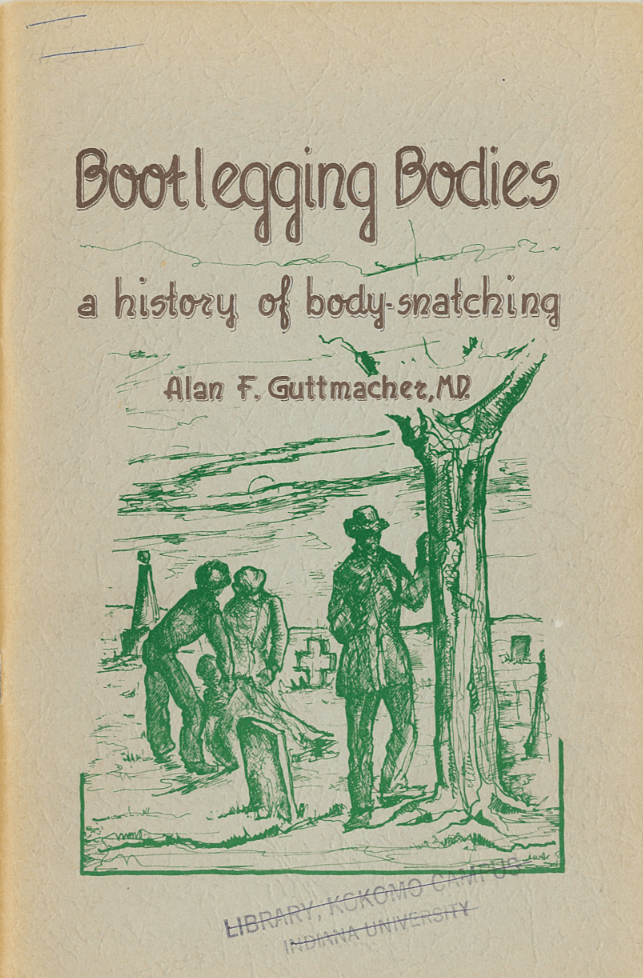

As knowledge slowly spread, so did “a heightened interest in medicine, with a special emphasis on human anatomy. This impetus to study the human body exactly, instead of superficially, seems to have been the result of a slow accumulation. The medical faculties began to realize that their anatomic knowledge was founded rather on uncertain tradition rather than on science; they began to realize that their ignorance of anatomy retarded their advance in the general art of healing.”iii The numbers of both hospital medical schools and private schools of anatomy grew, and eventually students, too, began to do dissections (instead of merely watching the professor perform this task). According to Guttmacher (p. 8-11), there were more than 200 students of anatomy in London alone by 1793, and more than 1000 by 1823. In 1828 the 12 dissecting rooms in London needed 800 bodies to keep up with demand. The only legal means of acquiring bodies for dissections was from the gallows, but those provided an average of 80 bodies a year for those 1000 students. Supply could not keep up with demand.

You probably have guessed by now that if legal means were insufficient, then illegal means were bound to arise. University Archives and Special Collections (UASC) has this interesting booklet that addresses this latter way of supplying that need. In Britain, 3 factors paved the downward spiral from the legal methods of obtaining bodies to body-snatching to outright murder. 1) In 1541 the Royal Company of Barbers and Surgeons were allotted 4 executed felons annually for dissection. The use of felons, i.e., degraded outcasts, caused many of the general public to associate dissection itself as a degrading practice. 2) The 1752 Murder Act gave rise to the fear that murder was becoming more common and therefore something “worse” than death was needed as a deterrent. “The Act functioned to entrench further deep seated popular fears of dissection … fueling violent confrontations and occasional riots between surgeons bent on retrieving an executed felon and the deceased’s bereaved relatives who desired a Christian burial.”iv 3) According to legal standards, body-snatching was not a crime, but merely a misdemeanor because a corpse had no value as property. “Lawyers argued that because the previous occupant had vacated the body, its ownership was in doubt.”v

Body snatchers, sometimes called resurrectionists, weren’t just a European phenomenon. Baltimore, MD, with its 7 medical schools, certainly saw its share of this business. Because the climate in Baltimore was temperate, it was possible to dig up graves in winter. Baltimore also had access to railroads, shipping bodies as far as St. Louis or Atlanta. Bayview Asylum also proved to be a valuable resource: “There in a section in the woods, simple pine boxes were laid out in open pits under a thin veneer of earth cover until a section filled up. Only then were the graves packed and sodded. Pickings were easy, and resurrectionists raided Bayview day and night, once in the middle of the asylum’s board meeting.”vi The state of Ohio saw a record enrollment in its medical colleges after the Civil War, leading to more business for would-be resurrectionists.

How would a body be stolen from the grave? “A common trick of the trade was to burrow into the head end of the grave and drag the corpse out with a rope tied around its neck. A more subtle method was to dig a hole at a certain distance from the grave and tunnel the body out without anyone knowing the grave had been disturbed. The shroud and grave goods would often be left in the grave on removal of the body, as court sentences were lighter for body snatching alone.”vii This last sentence is important–the theft of the actual body was only a misdemeanor, but taking anything else (clothes, articles, shroud, etc.) was property theft.

Removing a body from a grave might have been relatively simple as the practice of body snatching began, but as it grew more prevalent and public outrage arose, a simple ‘pop in and grab the body and get out’ was no longer sufficient. “Such was the prevalence of body snatching that graves increasingly started to become fortified. Mausoleums, vaults and table tombstones became popular amongst the rich. Meanwhile the poor would place stones or flowers on the grave to detect any movement in the soil that might betray a theft, or dig branches and brambles into the grave to make tunnelling more difficult. Body snatching was so rife in Scotland that in 1816 ‘Mortsafes’ were invented. These complex iron cages were bought or rented out until the body was sufficiently decomposed to deter the robbers. For further precaution, in some cemeteries friends would stay watch over graveyards at night, with watch towers sometimes being erected for the purpose.”viii Sometimes bodies would be kept in solid stone houses until they decayed to the point of no longer being usable for dissection and then buried. Other times an iron coffin was used–admittedly, these could be broken open, but doing so was too noisy to escape detection.

Dating from the early 19th century, this heavy cast iron mort-safe would be placed over newly buried graves for several days as a precaution to prevent corpses being stolen by “Resurrectionists” and sold to medical schools for anatomical dissection. Relatives and church office-bearers would also mount a guard from the watch-house, the small building seen here. Image found here.

William Burke and William Hare were two Irishmen who made Edinburgh their hunting ground when mere grave-robbing was not enough. In a period of some 8.5 months in 1828 they murdered 16 people, usually by getting the victims drunk and then smothering them. When captured, Hare turned state’s evidence and escaped death. Burke confessed and was hanged in a public square with a large crowd in attendance. His body was publicly displayed in the anatomy theatre before a day long parade of some 25,000 visitors. Today his skeleton is in the Anatomical Museum in Edinburgh.

Grave-robbing as a ‘thriving’ business came to an end in Britain with the passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832. The act repealed the compulsory dissection of murderers and allowed bodies that were unclaimed after 48 hours to be given to anatomy classes (unless the deceased had previously expressed a wish that this not occur). Due to a growing interest in and appreciation for the lessons learned via dissection, people began to donate their bodies to science. In the United States decisions of this sort were made on a state by state basis at different times and with differing criteria. 1899 saw the last case of U.S. body snatching, in Maryland.

One bizarre final story comes from the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, and (at least tangentially) involves the American presidency. John Scott Harrison was “the son of one President–William Henry Harrison–and the father of another–Benjamin Harrison. JSH’s political career was not quite as storied as his father or his son; two terms as a Congressman from Ohio (1853-1857) marked the extent of his own political achievement. … JSH died on May 25, 1878, at the age of seventy-three and was buried in the family plot in North Bend, OH. The same week, 23-year-old Augustus Devin died of tuberculosis and was buried in the same cemetery. During Harrison’s funeral, it was uncovered that Devin’s body had been removed from its final resting place. Fearing it had been taken as a cadaver, Harrison’s son–also named John– and his cousin George Eaton began to search the local medical colleges for Devin’s body. Their search eventually led them to Cincinnati’s Ohio Medical College on May 30, 1878. While they found no sign of Devin, they discovered a windlass with a taut rope leading to an underground space, whereupon John Harrison operated a winch to lift the rope only to find his father’s remains hanging on the other end! The stunning discovery of John Scott Harrison prompted a scandal in Ohio and attracted national attention. … Son and future president Benjamin was understandably livid at the robbing of his father’s grave and filed suit against the college (the results of the suit have been lost). Incidentally, Devin’s remains were eventually discovered among the specimens in Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan. The scandal prompted several states to pass acts to provide medical specimens for dissection.”ix

Happy Halloween!!

Notes

i Brenna, p. 2

ii Guttmacher, p. 2

iii Gutmacher, p. 6

iv Ross, p. 109

v. Pietila

vi. Pietila

vii. Rise

viii. Rise

ix. John

Resources Consulted

Guttmacher, Alan F. Bootlegging Bodies: A History of Body Snatching. Booklet prepared by the staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County, 1955. (UASC RH 022-9, Miscellaneous Regional Material Collection)

Lennox, Suzie. “The Art of Body Snatching.” Historic UK website, published January 11, 2015.

Leave a comment