*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

This title is from the name of a 1946 Broadway musical about Annie Oakley, music and lyrics by Irving Berlin, that became a film in 1950, and has had multiple revivals since. Let’s see if we can find the “real” Annie amidst the hype.

Her parents, Jacob and Susan Moses (also found as Mosey or Mozee) moved their family, which at that time included 3 daughters, from Pennsylvania to Darke County, Ohio in 1855. The inn they had been operating in Pennsylvania burned, leaving them without an income. Their goal in moving was like many other pioneers, to own a farm and earn a living from it. Ohio had been a state since 1803 and the larger cities like Cincinnati and Cleveland were already thriving, but Darke County was in the western part of the state, near the border with Indiana, and was still a wilderness.

Life wasn’t easy, and all family members had to pitch in. Two more daughters were born, one dying at 8 months. This is the world into which Annie was born on August 13, 1860, named Phoebe Ann at birth, but always called Annie. Within four years she was joined by two more siblings. (Yet another was stillborn.) In 1866 events dealt the family’s survival a hard blow. “One cold December day, Jacob went into town to sell some grain and pick up some supplies. While he was gone, a blizzard set in. As the wind howled and the snow swirled around the cabin, the family waited anxiously for his return. Finally, in the middle of the night, Jacob’s horse-drawn wagon came into sight. Jacob was barely alive. Annie would later recall seeing her father “with the reins around his neck and wrists, for his dear hands had been frozen so he could not use them. His speech was gone.” The ordeal was too much for Jacob. He died a few weeks later. The loss of their father and husband was a huge blow to the Moses family–and not just emotionally. Without Jacob’s labor, the family couldn’t make a living from their land. …[Eventually], Susan had to sell their farm and move the family to a smaller, rented property.”i

The young Annie taught herself how to fire her father’s rifle and was able to help put food on the table. The family just squeaked by, but Annie’s oldest sister died of tuberculosis in 1867. Her younger sister was sent to live with a neighbor. By 1870 her mother had remarried, had another child, and was widowed once again. Things were desperate. “Mrs. Crawford Edington, the matron at the Darke County Infirmary, offered to take Annie in and train her in exchange for help with the children. The infirmary was in fact a poorhouse, apparently a dumping ground for the elderly, the orphaned, and the insane. Mrs. Edington taught Annie sewing, a skill that came in handy later when she made her own costumes. Annie was then offered the opportunity to work as a mother’s helper on a farm, taking care of a baby for pay and schooling.”ii Annie told the farmer that she enjoyed hunting and trapping, and he told her she’d have plenty of time to do this. It seemed like an ideal situation, but it was all a lie. The ten year old girl was treated as a slave–beaten, starved, and overworked. Letters were sent to Annie’s mother telling her how well the schoolwork was going and how much Annie liked living there. Again, nothing but lies. For the rest of her life Annie never referred to this family by name, only calling them ‘The Wolves.’ “Working for the wolves made Annie so tired that sometimes she fell asleep in the evenings before her work was done. When this happened on one cold winter night, Mrs. Wolf got so angry that she threw Annie out the door and into the snow. Annie thought she was going to die. …She was saved only by the appearance of Mr. Wolf. Worried that he’d be angry at her for putting the life of their near-slave in danger, Mrs. Wolf pulled Annie into the warm farmhouse.”iii

After two years, Annie could take no more. She ran away, returning to her mother in a new home and with a new husband. The reunion was a good one, but with the family still struggling, she chose to return to the infirmary, this time living with the Edington family. They were appalled at her treatment at the hands of ‘the wolves,’ and treated her as one of their family. They taught her how to read and write and continued the sewing lessons. “Annie spent about three years living with the Edingtons at the infirmary. Her time there had a big influence on her adult personality. Although she’d had a very hard childhood, in the infirmary she lived among people whose lives were even harder. When she won fame and money, Annie gave generously to charities–especially those that made children’s lives better. And she would often give children (especially orphans) free tickets to her shows and buy them treats like ice cream afterward.”iv

She returned home at age 15 and continued to help support her family. “Very soon Annie worked out a deal with the grocers Samson and Katzenberger, who had a flourishing grocery in Greenville, Ohio. They had known Annie from before and liked her. They soon agreed to buy whatever small game she cleaned and shipped to town. One thing the grocers noticed right away was the the quail, rabbit, or grouse Annie sent was not shot or torn up. She either caught the game in snares or shot them through the head, so the meat would be prime.”v The Katzenbergers also sold some of her game to stores in Dayton, Lebanon, and Cincinnati. Some sources say that her earnings enabled her to pay off the mortgage on the family farm. Annie Oakley was now making her living with a gun, through one means or another.

Her life took an interesting turn when she visited her older sister in Cincinnati and met with a storekeeper who had purchased her game. He was fascinated with her shooting ability and sponsored her in a shooting match with his guest, Frank Butler, a man who did exhibition shooting. (Brief Butler bio: Irish immigrant, born circa 1850, who came to this country at age 13 and did a variety of odd jobs until getting into exhibition shooting.) Another source says that Butler met some farmers who proposed a match between Butler and an unknown opponent, offering the winner $100. Butler was willing, albeit a bit reluctant to take money from these ‘rubes’, sure that he would win…..but he wasn’t about to turn down the money. He thought they were having a joke on him when a small (Annie was always a petite woman), young (depending on when this took place, she was between 15-20) showed up with a gun nearly as big as she was. Despite never having done any trap-shooting before, she beat him in a close contest. Butler lost the match and also lost his heart. (SORRY….corny but irresistible.) The two were soon married, remaining so for 50 years until their deaths. One additional point here….some sources say that her last name, Oakley, came the location of this shooting match, a district northeast of Cincinnati.

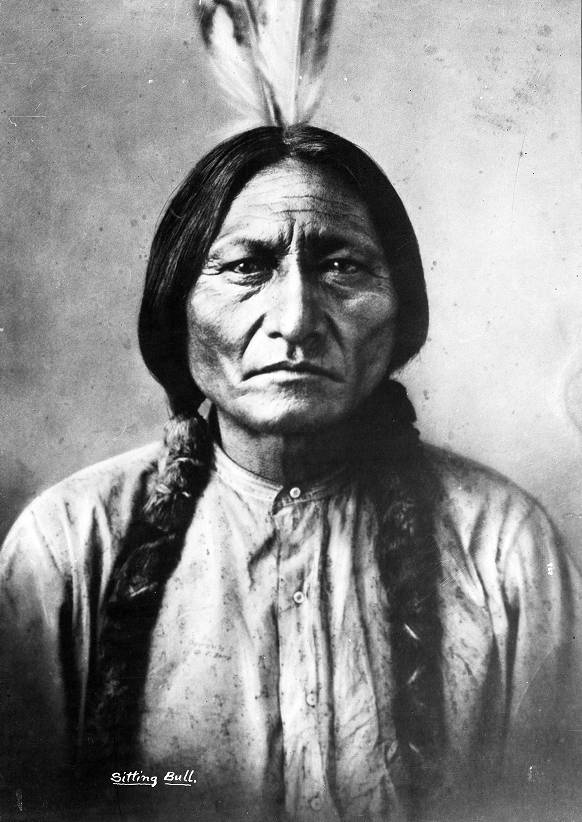

For the next few years Oakley and Butler toured as a shooting act, as part of vaudeville shows, with other shooters, or with circuses. Frank taught Annie about the theatricality of performing, but it was soon clear she was the better shot. She took center stage, with him as manager. In 1884 the great Sioux chief Sitting Bull saw Annie shoot in St. Paul, MN and was entranced. He asked to meet her and persisted when she initially turned him down because she was exhausted. “When they met, Sitting Bull gave Annie a new nickname–Watanya Cecila, which meant “Little Sure Shoot” in Lakota, the Sioux language. Besides his admiration for Annie’s shooting, Sitting Bull was struck by how much she looked like his own daughter, who had died years earlier. The chief gave her several presents, including the moccasins he’d worn at the Little Bighorn fight. Later, a legend would spring up that Sitting Bull had officially adopted “Little Sure Shot” as a daughter. There’s no proof of this, but the two certainly became friends.”vi

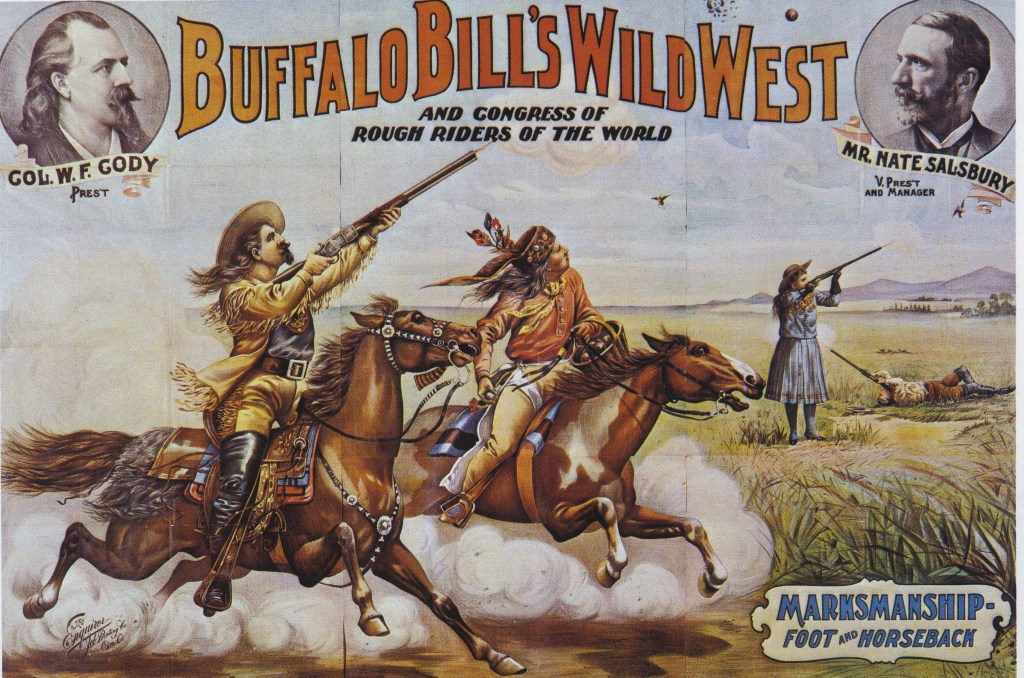

Shortly after this meeting, the Oakley and Butler act joined the Sells Brothers Circus. The income was good, but neither one was completely satisfied. In December 1884 they were on tour in New Orleans, and visited Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, also on tour. They were impressed with the care given the animals, and felt that the show was wholesome and educational. They offered to try out their act with the show, but were initially met with reluctance due to the fact that the show already had a shooting act and was without funds to pay for another. Fortuitously, that shooting act withdrew from Cody’s show and Oakley and Butler were invited to try out when the tour moved to Louisville, KY in 1885. In April 1885, Buffalo Bill and company “were encamped at Louisville’s baseball park….where the Butlers found the corral, the wigwams, and the mess tent. They got out their guns and Annie practiced while waiting to see Buffalo Bill. She sighted with a hand mirror and shot backward as Frank threw glass balls in the air. She hit them all. Just at that moment a tall bearded man in a bowler hat approached them and introduced himself as Nate Salsbury [manager of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West]. …Salsbury took the Butlers to the mess tent, where Buffalo Bill joined them, dressed in his best buckskin jacket, the silk handkerchief around his neck held by the diamond pin that Grand Duke Alexis had presented to him. He swept his sombrero off his flowing locks with a courtly flourish. “They told me about you, Missy. We’re glad to have you.””vii

Thus began a partnership that would span 17 years. Although Cody and Oakley had vastly different temperaments, they maintained a very warm and cordial relationship. He called her Little Missie, and she referred to him as Colonel. After Cody, she was the highest paid performer, and one of only a few featured in the show’s advertising.

When Buffalo Bill’s Wild West embarked on its European tours, Annie proved a great hit. This had to have been a big deal from a girl from backwoods Ohio, but she seemed to take it all in stride. In the 1887 performance for Queen Victoria’s jubilee, the queen even unbent enough to tell Annie, “You are a very clever little girl.” In meeting Edward, Prince of Wales and his wife, Princess Alexandra, she committed a faux pas that could have turned into a diplomatic nightmare. “According to tradition, anyone meeting the royal couple was supposed to greet the prince first. When Annie was introduced to Edward and Alexandra, however, she made a point of shaking hands with the Princess first. “You’ll have to excuse me, please,” Annie told the Prince, “because I am an American and in America, ladies come first.””viii Fortunately, her popularity was so great that this ‘no-no’ was attributed to naivete and forgiven. In reality, Annie, although never one to call herself a feminist, did not approve of his boorish, unfaithful treatment of his wife and was subtly making that point. She got by with it! During the 1889 tour to Paris’ Great Universal Exhibition, France’s celebration of 100 years since the French Revolution, it first appeared as though the French were not impressed. Annie came on stage and soon won the day. “The president of France told Annie that he’d make her an officer in the French Army if she ever decided to leave show business. The king of Senegal, one of France’s colonies in Africa, wanted Annie to come home with him to shoot the tigers that sometimes killed his people.”is

Annie and Frank continued to tour with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West until October 1901. They were aboard a tour train in Virginia when it had a head-on collision. No humans were killed, but at least 100 horses died. Neither Annie nor Frank was badly hurt and recovered quickly, but she saw this as a time to call it quits. This did NOT mean they retired, continuing to perform as a shooting act as well as appearing in plays. From 1911-1913 they were back on the road in the U.S. and Canada with a show called Young Buffalo Wild West (no affiliation with Cody). They then retired to a seaside cottage in Cambridge, MD, offering shooting lessons, visiting with friends, and doing charitable work, particularly for causes related to WWI soldiers.

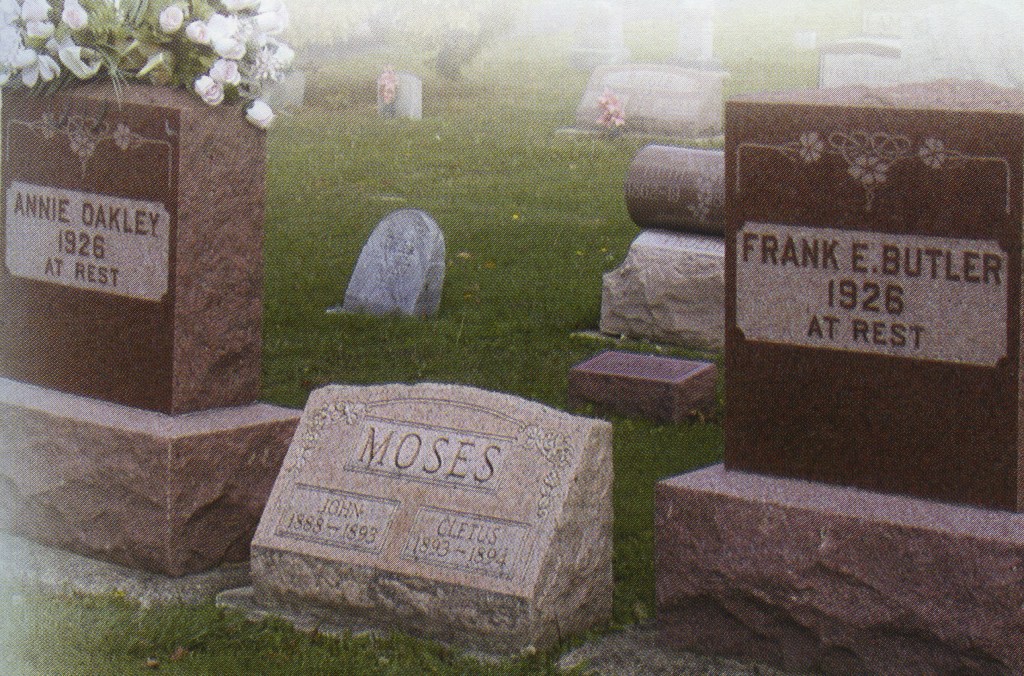

On November 9. 1922, they were in a horrific traffic accident that eventually left Annie needing a metal brace on her right leg. They initially moved back to Ohio, staying with one of Annie’s nieces. Suffering from anemia, her health began to fail. Frank had gone to Michigan to deal with his own health issues. Annie died in her sleep, at the age of 66, on November 3, 1926. Frank followed her in death just 18 days later. Theirs was a remarkable partnership that continued even in death.

Footnotes

iWills, p. 13-14

ii Carter, p. 270

iii Wills, p. 21-22

iv Wills, p. 25-26

v McMurtry, p. 147

vi Wills, p. 48

viiCarter, p. 274-275

viii Wills, p. 76

ix Wills, p. 84

Resources Consulted (note: all the books listed here are from the newly received Dunwoody Circus collection–if you want to see any of them, please ask in UASC)

Anderson, Ashlee. “Annie Oakley.” National Women’s History Museum website, 2018.

Biography: Annie Oakley. The American Experience, PBS website

Buffalo Bill Center of the West website : Annie Oakley

Carter, Robert A. Buffalo Bill Cody: The Man Behind the Legacy. New York: Wiley and Sons, 2000.

Gallop, Alan. Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2001.

Klein, Christopher. 10 Things Yu May Not Know About Annie Oakley. History.com, July 13, 2021.

McMurtry, Larry. The Colonel and Little Missie. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Wills, Chuck. Annie Oakley. New York: DK Publishing, 2007.

Wilson, R. L. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: an American Legend. New York: Random House, 1998.

Leave a comment