*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian

Mark Twain once wrote, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” Twain, a man who surely knew the value of a good story, wasn’t speaking about Buffalo Bill Cody, but he could have been. Cody was a larger than life figure, whose real life adventures became the stuff of legends throughout his life, mostly through his extremely popular Wild West shows that toured the country and even abroad.

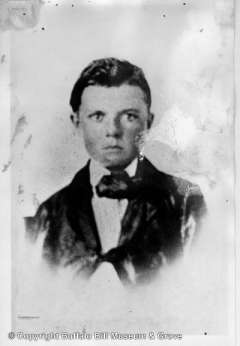

William Frederick Cody, later aka Buffalo Bill, was born February 26, 1846 in Iowa. The family moved to Kansas (then a territory) in 1854. “It should be mentioned here that for at least ten years before the Civil War, and another ten years after it, Kansas and Missouri were probably the most dangerous places in America–places were neighbor often fought neighbor and brother brother. The trouble was slavery: it was in Kansas and Missouri that passions over slaveholding were the most intense; they didn’t call it “Bleeding Kansas” for nothing. Guerilla activity, vigilantism, and homegrown militias flourished and fought. In these parts the Civil War lasted something like twenty years, rather than four.”i This scenario set up one of the major changes in the life of young Cody. His father, Isaac, wasn’t an abolitionist, but he also did not want more slaves being brought into Kansas. In 1854, an enraged pro-slavery advocate, seeing Isaac’s stance as too tepid, stabbed him. He recovered, but died 3 years later.

Hardship faced the family with the loss of Isaac’s income. As of 1858 there were Cody, his mother, and 4 sisters to support. Cody got a job with the freighting firm of Majors and Russell, a company that three years later became the famous Pony Express. “It was from these three-mile deliveries that young Bill Cody rose, in a natural sequence, to being a drover, cowboy, herdsman, teamster, helping to move livestock or freight from one location to another–this mostly meant delivering beef on the hoof to sometimes distant army posts. He was eleven at the time. … In the 1850s and 1860s it was perfectly normal for rural youths to be expected to do a man’s work at the age of eleven or twelve.”ii Later in life, his years riding for the Pony Express became an integral part of his Wild West shows.

North/South tensions continued to rise until the Civil War broke out in 1861. “At the time of the Civil War, teenagers were welcome in the ranks of both armies; drummers and fifers could be as young as sixteen and still enlist. Cody was now fifteen, and wanted to serve somehow.”iii But he had promised his seriously ill mother that he would not join the army; he honored his promise to his mother and his desire to serve by joining some of the many independent, “irregular”groups. His mother died in late November 1863; after making sure his sisters were taken care of, Cody enlisted on February 19, 1864, part of the 7th Kansas Cavalry. On September 29, 1865 he and the rest of his regiment were mustered out.

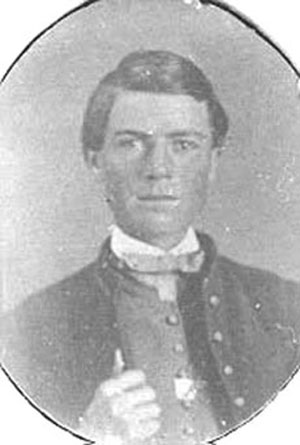

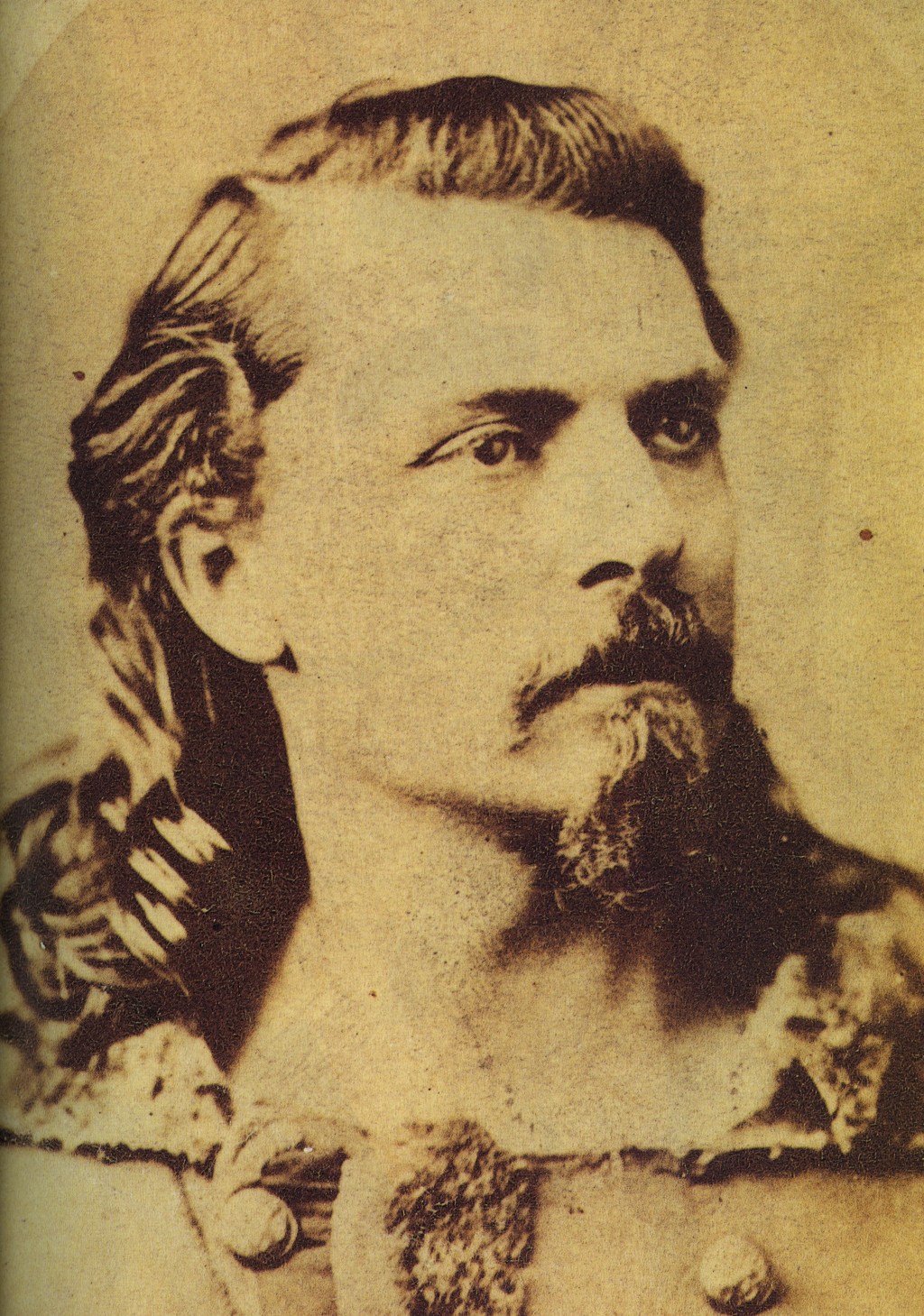

Less than a year after mustering out, the twenty year old Cody turned his attentions to domestic matters, marrying Louisa Frederici, a woman he had met in St. Louis late in the war. “It was not a marriage made in heaven. Of French descent, accustomed to a gracious city life, complete with maids and carriages, Louisa Frederici Cody disliked the West, with its rough accommodations and ever-present dangers. Highly volatile and emotional, she had the vanity of a spoiled daughter. A strikingly beautiful young woman, she expected flattery and constant attention; when things did not go as she wished, she became moody. This side of her personality was hard for Cody to comprehend. From the beginning of the marriage, she spent more time in St. Louis with her relatives than with him. Later in the marriage, she disliked show business as much as Cody loved it. The two spent longer periods of time apart; it is doubtful that Cody was ever at home for more than six consecutive months. …It is true that Cody, the plainsman cut a handsome figure, but for Louisa the Wild West held no allure whatever–nor was she cut out for the pioneer life.”iv Eventually 6 children were born to this union; the only son and one of the daughters died in childhood.

Railroads were a boom industry after the Civil War, one of which was the Kansas Pacific Railway. “By the 1870s, it operated many of the long-distance lines in Kansas and soon extended the national railway network westward across that state and into Colorado. The line opened up the settlement of the central Great Plains, and its link from Kansas City to Denver provided the last link in the coast-to-coast railway network in 1870.” Cody got a contract to provide food (i.e., hunt buffalo) for the workers. He was “to provide twelve buffalo a day for the railroad. Cody demanded–and received–a large salary for his work: $550 a month, a substantial sum in those days. He was paid so well because the work was dangerous. He had to travel…..five or ten miles from the safety of the fort every day, accompanied only by one man in a wagon to bring the meat back. There was always the risk of an Indian attack. The company hiring Cody got a bargain in any case, for the meat ended up costing them about a cent a pound. Only the hump and hindquarters were used; the rest was left on the prairie for scavengers.”v His success soon earned him the nickname by which he is still best known: Buffalo Bill.

In 1868 the U.S. Army hired Cody as a civilian scout and guide for the Fifth Cavalry. “Cody’s experience as a plainsman, his survival skills, and his marksmanship made him an invaluable tracker and fighter. … Buffalo Bill was awarded the [Congressional] Medal of Honor for valor during a skirmish with the Sioux on April 26, 1872, east of North Platte, Nebraska. His name, like those of four other scouts, was stricken from the Army’s Medal-of-Honor rolls in 1916 because he was a civilian at the time of the action. It was restored in 1989.”vi

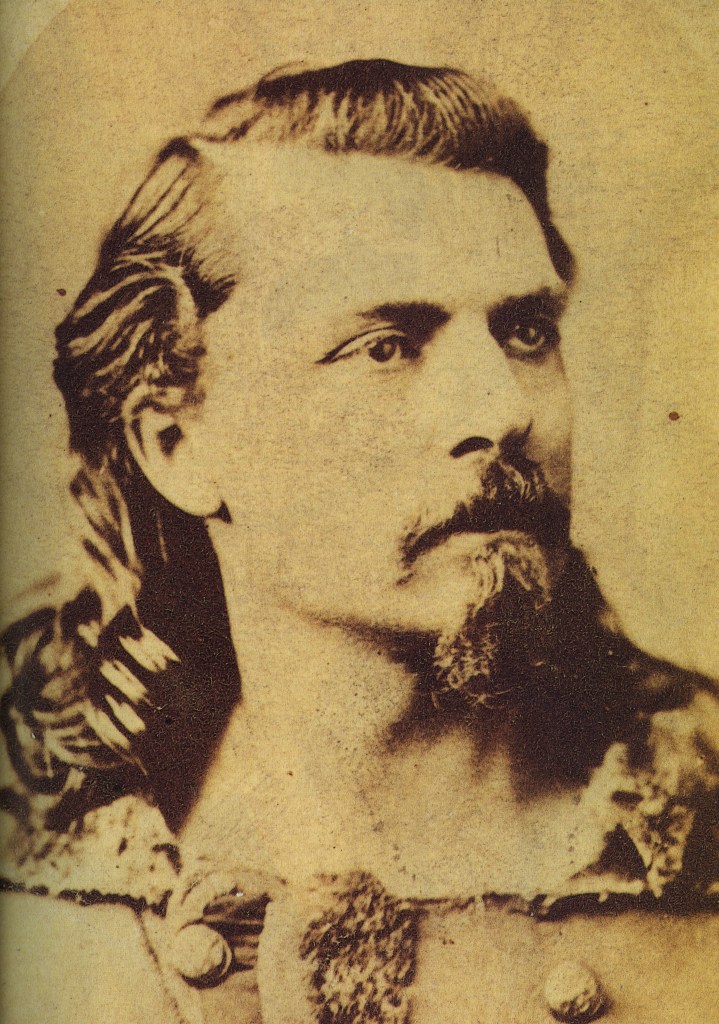

The West was indeed wild during Cody’s youth, and he had direct experiences with much of that wildness. But by 1872, “the American West was rapidly becoming civilized: the Civil War had ended only seven years before; in Germany a process for tanning buffalo hides had just been perfected, supporting the industrial revolution with tough leather belts; the wholesale slaughter of the Plains Indians’ food supply had been encouraged by the military to control the first Americans; and four years later General George Armstrong Custer’s famous “Custer luck” would run out in Montana. … Industrialization was reshaping American culture as the slow exodus from farms became a stampede to cities. … Daniel Boone, Kit Carson, and Jim Bridger told fantastic stories of the sights they had seen in their travels, sights which sounded far-fetched and mythic to the comfortable eastern public. … The myth of the rugged western frontiersman was about to enter a new realm as William Cody, or Buffalo Bill, started to capitalize on the Leatherstocking myth and elevate it to new heights.” vii Cody may have originally thought that he would live the rest of his life as a “gentleman rancher,” performing his shows only long enough to finance these aspirations, but his success overwhelmed this idea. “In fact, he became the ultimate showman, one who had lived the roles he would play. …. For the rest of his life, Cody would be recognized as an entertainer and interpreter of Western history.”viii

The earliest foray into show business was in a show entitled “Scouts of the Prairie,” which opened in Chicago December 16, 1872. “The play featured plainsmen Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro playing themselves, scriptwriter Ned Buntline as a trapper, and dancer and actress Giuseppina Morlacchi as an Indian maiden. The script was apparently adapted by Ned Buntline from a dime novel written by Ned Buntline. To put it mildly, it was not a critical tour de force. According to the Chicago Times: “On the whole it is not probable that Chicago will ever look upon the like again. Such a combination of incongruous drama, execrable acting, renowned performers, mixed audience, intolerable stench, scalping, blood and thunder is not likely to be vouchsafed to a city for a second time – even Chicago.” Scouts of the Prairie may not have delighted the critics but it was a rousing financial success. Artistic merit be damned, the audience was thrilled to view the likes of famous plainsmen Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack and the accomplished and attractive Giuseppina Morlacchi. The show proceeded to tour other major American cities where it was likewise received with enthusiasm in spite of its artistic limitations.”

Cody was no fool. He used this experience to hone his craft, to train and improve. By 1880 his time with Buntline ended and he was ready to present his own version of the Wild West. Nate Salisbury was hired to be the manager of his show, a pairing that proved fortunate for both. Salisbury was an excellent manager and recognizer of talent…..he “discovered” Annie Oakley performing in various venues and hired her immediately. Both Cody and Oakley were consummate performers.

These shows were enormously popular, playing to huge crowds. Actually, they were not seen as shows, nor did Cody call them that. “It was, in his mind, and in the minds of most of the spectators, history, not fiction–easy to understand fiction that allowed the audience to participate vicariously in the great and glorious adventure that had been the settling of the West, an enterprise not yet wholly concluded even in 1886.”ix Nearly everyone, from hardened journalists to wildly enthusiastic audiences, accepted that this illusion was indeed reality.

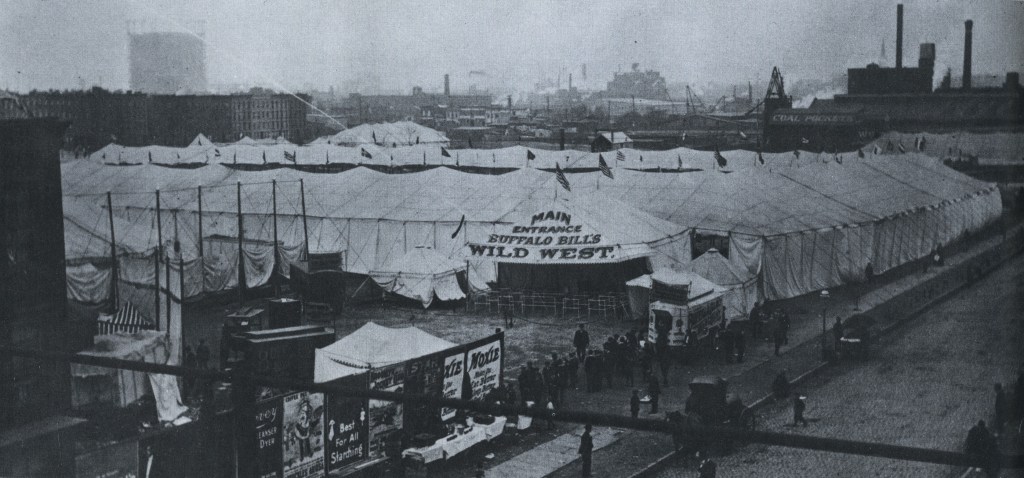

The shows grew huge. “The business of running Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was very complicated. The management teams….supported thousands of people who worked for Cody. … It was a huge operation encompassing eleven acres of ground. The arena was 150 feet by 320 feet, and when the exhibition remained in one location for a long time the surface was regulated–drained when wet and sprinkled when dry. During long stays elaborate scenery was used, which was composed of massive painted backdrops with as many as seven panoramas, each 200 feet long and 30 feet high. Although the figures fluctuated due to various factors, such as location, according to Salisbury in an interview during the 1892 London season, to produce Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, it took 22,750 yards of canvas, 20 miles of rope, and 1,104 stakes. Four teams of eighteen men each were assigned specific duties during setup. Since Thomas Edison was a friend of Cody’s, it is not surprising that [the show] carried with it the largest private electrical plant in the existence at the time, capable of powering twenty-four 4,000-candle power carbon-arc floodlights; one 8,000-candle power searchlight; two 25,000-candle power searchlights; and the house and company lights….. [Such an enterprise] was expensive. When Buffalo

Bill’s Wild West was on the road, it cost approximately $4,000 a day to keep it going. To advertise an upcoming show, fliers, posters, and handbills would be circulated. This often led to “circus wars,” where competing outfits would fight for billboard space, the price of which would escalate. Such wars were expensive and could bankrupt an outfit.”x

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was quintessentially an American study, but it held a great deal of appeal overseas, too. Great Britain was set to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1887–50 years on the throne. The Jubilee would be very, very British…..foreigners could come and see, but only at a distance. “But there was an exception. Without seeking anyone’s official permission, the United States of America announced its intention to send a large delegation to the festivities. Britain’s ‘American cousins’ planned to celebrate the Jubilee in a unique way, giving tens of thousands of Britons flocking to London for the event a special transatlantic treat. … What the Americans planned for London was a unique ‘American Exhibition’ right in the heart of Britain’s capital, showing off everything that they claimed to lead the word with at that time. … [Cody’s show was one part of the American Exhibition.] Now he was coming to London in the role which had made him so famous at home, as a showman reproducing life in America’s untamed west for folks living in the civilized east who had never seen genuine Indians or hard-living cowboys, ridden a stagecoach, witnessed sharpshooters in action or thrilled as a bronco buster hung on for life to the back of a wild mustang.”xi

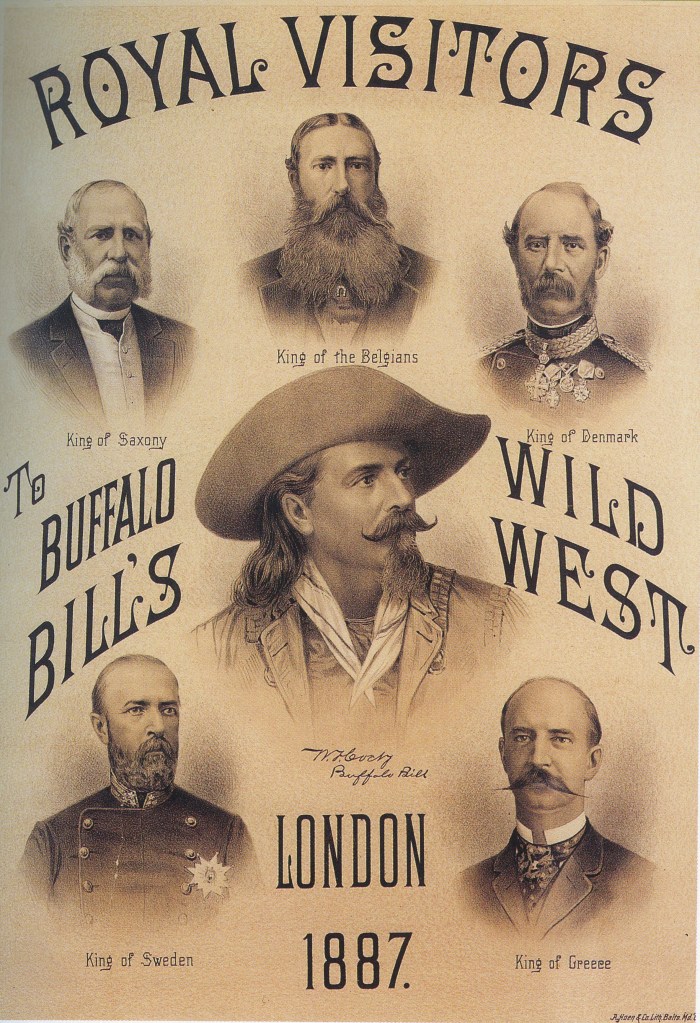

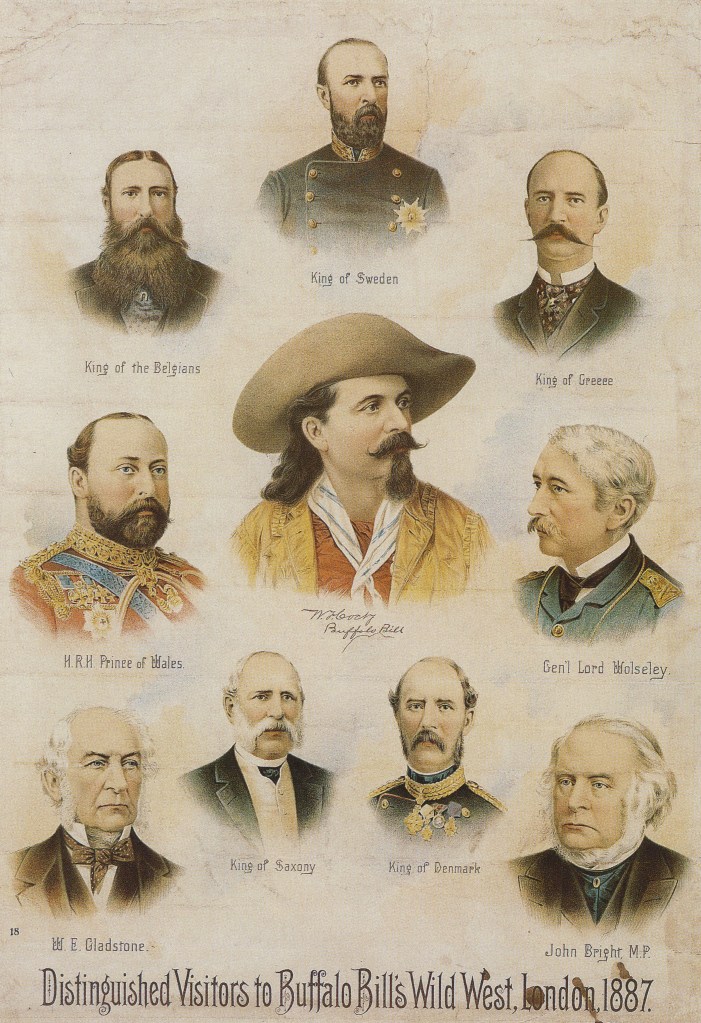

The Queen of Belgium was said to have remarked that she came to London not for the Jubilee, but rather to see the Wild West performance. In addition to Belgium, the kings of Denmark, Greece, and Saxony were in attendance, as well as many other royal family members. Cody seemed to be very much at ease with the many eminent personages there. When asked by the Prince of Wales if he had ever played before four kings before, he quipped, “I have, Your Royal Highness, but I never held such a royal flush as this against four kings.” The Prince was delighted and roared with laughter, and explained this to those present who knew nothing about the game of poker. Even the famously withdrawn Queen Victoria enjoyed the performance, telling Annie Oakley, “You are a very clever little girl.” She further invited them back for a command performance at Windsor Castle on June 26, 1892.

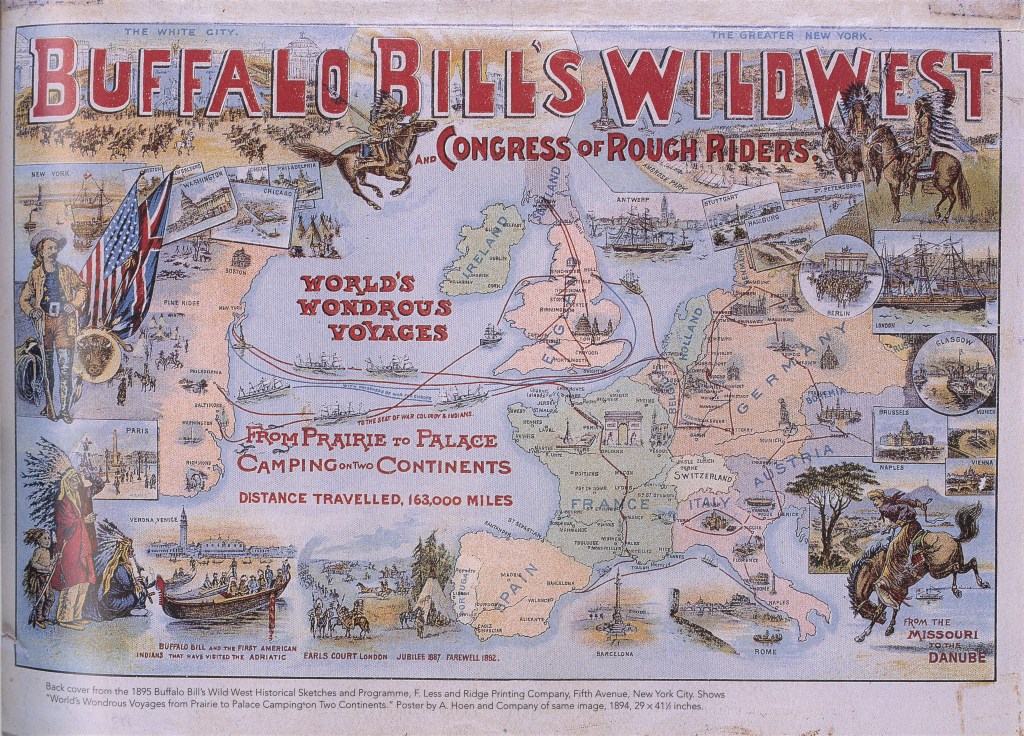

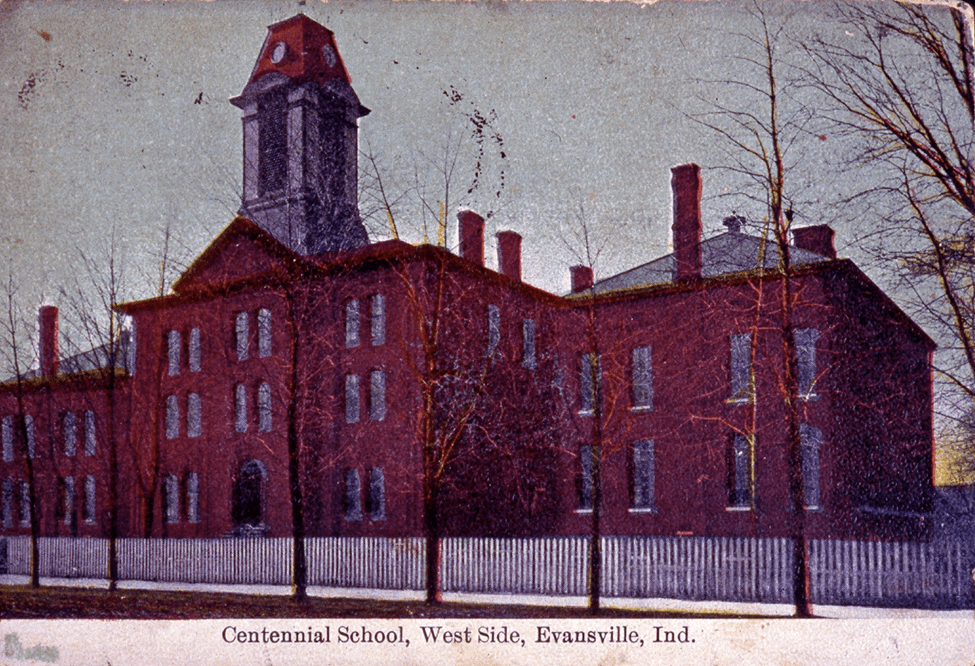

In addition to England, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (or a differently-named version of this show) toured Austria, Belgium, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy (on the 1890 tour, while in Rome, they were invited to visit the Vatican, including an audience with Pope Leo XIII), Luxemburg, Scotland, Spain, and Wales….some locations multiple times. The 1889 visit to Paris was to appear in the Great Universal Exhibition, France’s celebration of 100 years since the French revolution. There was one other attraction in Paris at the same time…..the opening of the Eiffel Tower! There were 8 European tours 1887-1892 and 1902-1906. They toured all U.S. states in existence at that time as well as Washington, DC. There were multiple tours of Indiana; in 1875, 1878, 1879, 1881, 1882, 1884, 1896, 1898, 1901, 1907, and 1913, these tours included stops in Evansville. Check out “Did Buffalo Bill Visit Your Town?” to see if your hometown was ever treated to such a performance.

Like all bigger-than-life legends, Buffalo Bill had his critics. Two of the biggest issues raised were his contributions to the demise of the buffalo and his treatment or attitude about Native Americans. Let’s take a look at these issues, starting with the buffalo. Numbers vary widely, but an average estimate for the number of buffalo circa 1800 would be 30-60 million. By 1884 there were some 325 wild buffalo in the United States. “During his employment as a hunter for the railroad company–a period of less than eighteen months–Bill claimed to have shot 4, 280 buffalo. … In later years Buffalo Bill himself was horrified at the destruction of the animal he had helped to wipe out in such vast numbers, unaware at the time that his contribution to their mass slaughter would almost remove the buffalo from the face of the earth. With the creation of his Wild West entertainment, Bill later became a buffalo preserver and by 1890 his herd….was the third largest in captivity.”xii Another source says, “The railroads were a major cause of extermination. They continually cut the herds’ grazing territory and also advertised for “sportsmen” to ride the trains and shoot out the windows to satisfy their pernicious need to kill. Unfortunately, these sportsmen rarely killed the animals but only wounded them. Perhaps the deadliest foe of the buffalo were hide hunters. …. Many of these hide hunters felt that the buffalo supply was endless; in addition, their activities were encouraged by the military, which wanted the buffalo herds eliminated to force the Indians onto the reservations. …By exhibiting buffalo in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Cody helped focus the world’s attention on the fact that buffalo were rapidly becoming extinct.”xiii (Fortunately, according the the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Currently, there are approximately 20,500 Plains bison in conservation herds and an additional 420,000 in commercial herds. While bison are no longer threatened with extinction, the species faces other challenges. The loss of genetic diversity, combined with the loss of natural selection forces, threatens the ecological restoration of bison as wildlife. A low level of cattle gene introgression is prevalent in most, if not all, bison herds.”)

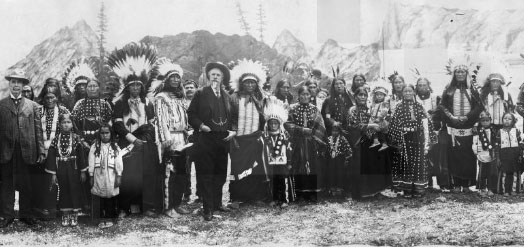

As is clear from the images immediately above and below (one panoramic picture in 3 pieces), Native Americans were a large part of every Wild West performance. They certainly added veracity to the performances, but were they being exploited? What was Cody’s relationship with them? This is a thorny issue that can never be fully settled, but the resources consulted for this blog generally agree that Cody was a generous man with sympathy for the plight of the Native Americans. True, early in his show business career he was touted as an Indian killer, but the evidence is not clear that this claim was true. “Cody was never an Indian hater, as so many of his contemporaries were. He was not moved to kill Indians, but merely to avoid being killed by them.”xiv In some of the programs that accompanied the Wild West performances, there was an “attempt to educate whites about the true nature of Indians. Cody had an insert put in the 1893 program pleading for just and humane treatment of Indians–stating that Indians make good soldiers, farmers, and citizens if they are given a chance. Thus the programs expressed hope for better understanding between the races.”xv What is most telling perhaps is how Native Americans felt about Cody. “In his years as a showman he probably employed more Indians than all the other shows put together. … He continued to hire Indians over the protests of the Department of the Interior and the commissioner of Indian Affairs, who didn’t at all like the fact that Indians were becoming show business stars. … Moreover, the Indians he employed liked him and let it be known that he treated them well. When the first Indian protective agencies were formed, Cody was more than once accused of mistreating Indians on his European tours, but the Indians themselves hurried to refute these charges.”xvi An explanation of this criticism is that the government wanted to assimilate Native Americans, while Cody wanted to promote their culture.

Time and circumstances conspired to somewhat diminish the glamour of the legend of Buffalo Bill Cody. Noted earlier was the fact that his marriage was not a happy one. He was all about living the life of a cowboy turned showman; she wanted nothing to do with that and did not tour with him. Back in 1878 he had purchased land in North Platte, Nebraska and built a house and ranch he called Scout’s Rest. Over the years he sent her money to purchase more land for the ranch. She did so, but she put it all in her name. When Cody

found out, he was devastated. In 1904 he sued for divorce. “After postponements and a change of venue from Sheridan to Cheyenne, Wyoming, the divorce hearing began on February 16, 1905, with Judge R.H. Scott presiding. The hearing attracted the press and did a lot to tarnish Cody’s reputation. Cody accused Lulu of trying to poison him on two occasions and complained that Lulu was rude to his guests and a nag to him. Lulu accused Cody of having affairs with several women, including Queen Victoria. Finally, Judge Scott threw the case out of court. Although they eventually reconciled on July 28, 1910, the hearing had shown the American public another, less heroic side to Cody they had not seen on the Plains or onstage.”xvii Crippling production costs combined with lowered interest meant he had to sell his show and assets at a sheriff’s auction in 1913. Other business ventures failed. And by 1915, American audiences were seeing newsreels of World War I ugliness–the romantic appeal of the western hero was long gone.

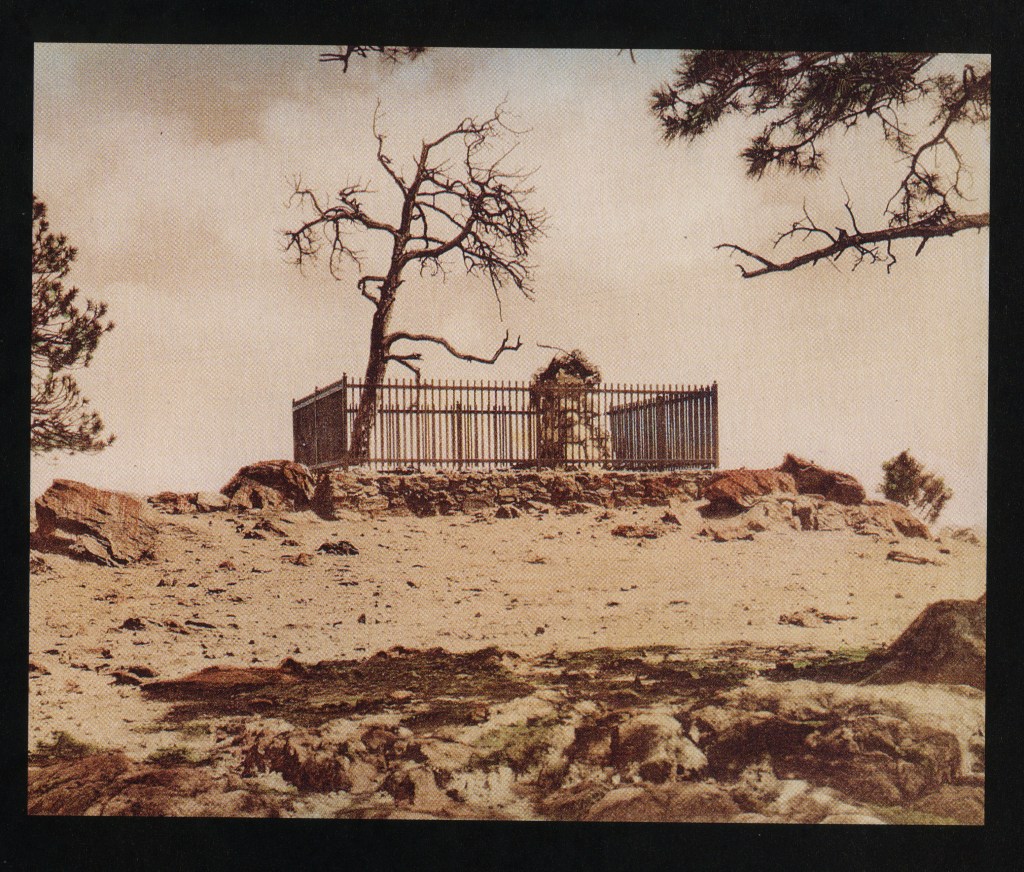

Age caught up with the old scout, who died at his sister’s house in Denver on January 10, 1917. His 1906 will stated his wish to be buried overlooking Cody, Wyoming, but this was not to be. His wife contested the will, which left her virtually nothing, and produced a 1913 document that left everything to her (given his indebtedness at that time, this was not much). She further claimed that he had requested to be buried on Lookout Mountain, CO. There is some contention that she was bribed by a Denver newspaper magnate named Harry Tamman to have Cody buried in Colorado, close to Denver and thus more of a draw to tourists. The death of William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody was front page news worldwide, drawing tributes from King George V of England, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, and former president Theodore Roosevelt. One source said that there has never since been such a huge funeral in Colorado.

Almost as big a star as Buffalo Bill was Annie Oakley. You’ll note that she’s only been mentioned in passing…..Miss Oakley merited a blog of her own! As we say goodbye to Buffalo Bill, you can look back to the Annie Oakley blog, published in November 2024. Just look at the Archives link in the right hand column and click on that date.

Footnotes

i McMurtry, p. 36

ii McMurtry, p. 37-8

iii Carter, p. 62

iv Carter, p. 81-82

v Carter, p. 95

vi Buffalo Bill Museum, p. 17

vii Sorg, p. 3

viii Buffalo Bill Museum, p. 21

ix McMurtry, p. 139

x Sorg, p. 71-74

xi Gallop, p. x-xi

xii Gallop, p. 6-7

xiii Sorg, p. 94-95

xiv McMurtry, p. 44

xv Sorg, p. 51

xvi McMurtry, p. 43

xvii Sorg, p. 60

Resources Consulted (note: all the books listed here are from the newly received Dunwoody Circus collection–if you want to see any of them, please ask in UASC)

Buffalo Bill and the Wild West. Brooklyn, NY: The Brooklyn Museum, 1981.

Buffalo Bill Center of the West website

Wild West Shows: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

Buffalo Bill Museum. Cody, WY: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1995.

Carter, Robert A. Buffalo Bill Cody: The Man Behind the Legacy. New York: Wiley and Sons, 2000.

“Did Buffalo Bill Visit Your Town? Compiled by the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, CO

Gallop, Alan. Buffalo Bill’s British Wild West. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2001.

“Kansas Pacific Railway.” Legends of America website.

McMurtry, Larry. The Colonel and Little Missie. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

“Plains Bison.” U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, FWS Focus webpage.

Russell, Don. “Cody, Kings, and Coronets.” The American West, v.7: no.4, July 1970, p. 4-10, 62.

Seligman, Daniel R. “Scouts of the Prairie: A Glorious Disaster.” Legends of America website, 2022.

Sorg, Eric. Buffalo Bill Myth & Reality. Santa Fe, NM: Ancient City Press, 1998.

Wilson, R. L. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: an American Legend. New York: Random House, 1998.

Leave a comment