*Post written by Mona Meyer, Archives and Special Collections Metadata Librarian.

If you’re from this area and/or have ever visited New Harmony, Indiana, then you’ve heard of Robert Owen. You may also know that New Harmony is the site of two historic experiments in living communally, and that Owen was the source of the second of these experiments. And if you’ve heard of none of this, check out Visit New Harmony for a brief overview, or better yet, get in your car and physically visit. It’s a short drive from USI. This blog is going to focus mostly on Owen and his views on society.

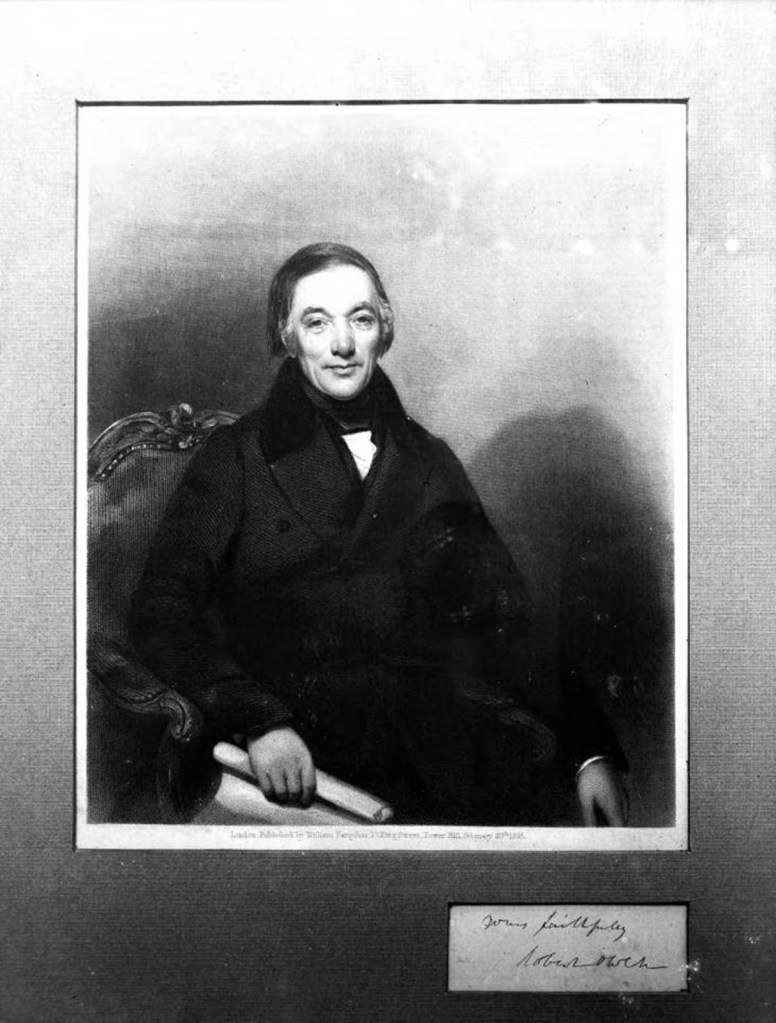

Robert Owen (1771-1858) was born in Newtown, Montgomeryshire, Wales, the 6th of 7 children of the local postmaster/saddler/ironmonger) and his wife. His official schooling ended at age 10 when he was apprenticed to a cloth merchant in an English town about 100 miles north of London. He was, however, an avid reader, talking full advantage of his employer’s library to educate himself. By age 18-19, he had learned the trade sufficiently to be employed as a superintendent of a cotton mill in Manchester. “The population of Manchester increased by 1,000 per cent from 25,000 at the time of Owen’s birth to nearly a quarter of a million fifty years later. The demand by the cotton mills for labour was insatiable.” At that time, the Industrial Revolution had brought great prosperity to Manchester’s textile industry, so Owen found himself in a particularly good situation. The mill became “one of the foremost establishments of its kind in Great Britain. Owen made use of the first American Sea Island cotton (a fine, long-staple fibre) ever imported into Britain and made improvements in the quality of the cotton spun.“

The story to be told in this blog really begins in 1799, when Owen married Caroline Dale, the daughter of a Scottish philanthropist and owner of a large textile mill in Lanark, Scotland. Owen and several partners purchased this mill from his father-in-law, David Dale, and at the beginning of 1800, Owen became the mill’s manager. This provided him the stage to implement many of his ideas about social reform.

Life as a mill worker was hard. “The noise from machinery was deafening, many workers became skilled lip readers in order to communicate over the noise. Ear protection was not compulsory leading to many workers becoming deaf. The air in the cotton mills had to be kept hot and humid (65 to 80 degrees) to prevent the thread breaking. In such conditions it is not surprising that workers suffered from many illnesses. The air in the mill was thick with cotton dust which could lead to byssinosis, a lung disease. Although protective masks were introduced after the war, few workers wore them as they were made uncomfortable in the stifling conditions. Eye inflammation, deafness, tuberculosis, cancer of the mouth and of the groin (mule-spinners cancer)** could also be attributed to the working conditions in the mills. Long hours, difficult working conditions and moving machinery proved a dangerous combination. Accidents were common and could range from the loss of a finger to fatality.” (Personal story: I’ve toured the historic textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts. We were given disposable ear plugs and shown into a room with just a very small number of machines working. I thought the noise level was very tolerable, and I could easily hear and understand the guide. At the end of that room, we could dispose of the ear plugs as we moved to other areas. Once I removed the plugs, I was stunned at how incredibly loud it was, and remember that only a few machines were in operation. Clearly those ear plugs were far more important than I had realized. I cannot imagine working without any ear protection at all in a fully operational mill.) Hours were long (at least a 13-hour day, probably 6 days per week), with children as young as 7 (and quite possibly younger) employed. New Lanark had some 2,000 people, “500 of whom were young children from the poorhouses and charities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. The children, especially, had been well treated by the former proprietor, but their living conditions were harsh: crime and vice were bred by demoralizing conditions; education and sanitation were neglected; and housing conditions were intolerable.“

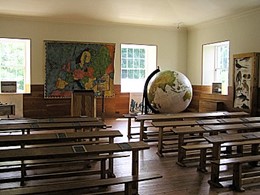

Recall that Robert Owen was a great reader. He was also a deep thinker and philosopher, seeking to put the things he’d learned in his reading into practice. “Owen set out to make New Lanark an experiment in philanthropic management from the outset. Owen believed that a person’s character is formed by the effects of their environment. Owen was convinced that if he created the right environment, he could produce rational, good and humane people. Owen argued that people were naturally good but they were corrupted by the harsh way they were treated. For example, Owen was a strong opponent of physical punishment in schools and factories and immediately banned its use in New Lanark. David Dale had originally built a large number of houses close to his factories in New Lanark. By the time Owen arrived, over 2,000 people lived in New Lanark village. One of the first decisions took when he became owner of New Lanark was to order the building of a school. Owen was convinced that education was crucially important in developing the type of person he wanted. He stopped employing children under ten and reduced their labour to ten hours a day. The young children went to the nursery and infant schools that Owen had built. Older children worked in the factory but also had to attend his secondary school for part of the day.“

Owen’s plan for reforming/remaking society started young. “Much good or evil is acquired or taught to children at an early age. Many ‘durable impressions’ are made even in the first year of a child’s life. Therefore, children uninstructed or badly instructed suffer injury in their character during their childhood and youth. It was in order to prevent this that the workers’ young children were to receive Owen’s closest attention. In the playground which was built for them at New Lanark each child would be told on his entrance in language he could understand that ‘he is never to injure his play-fellows: but that, on the contrary, he is to contribute all in his power to make him happy’. If this simple precept was followed—and the employment of superintendents was to ensure that there would be no deviation from it—then this behaviour would in time be transmitted to the population as a whole. To this end, Owen prescribed that the curriculum should be the best possible, eschewing traditional attitudes towards the education of the poor. Recognizing that each child had different aptitudes and qualities, he later pointed out that the intention of his system was not to attempt to make all human beings alike. Education was to make everybody ‘good, wise and happy’. Owen did not simply equate education with schooling. The role of parents in the process was stressed: the mother from the birth of a child onwards and certainly in the early years, was a key figure and both parents were urged to display great kindness in manners and feeling.”

With success at New Lanark, Owen’s horizons began to expand beyond education. As he developed his ideas, he became more of a communitarian and searched for opportunities to put his ideas into practice. In 1826, he “bought 30,000 acres of land in Indiana … from a religious community, renamed it New Harmony and began an experiment of his own. After a trial of about two years, [it] failed completely. … Under Owen’s guidance, life in the community was well-ordered for a time, but differences soon arose over the role of religion and the form of government. Numerous attempts at reorganization failed, though it was agreed that all the dissensions were conducted with an admirable spirit of cooperation. Owen withdrew from the community in 1828, having lost £40,000, 80 percent of all he owned.“

Just as the Industrial Revolution brought advances and great wealth (to the upper class), so it brought the opportunity to take advantage of the worker. Owen himself left school at age 10 to go to work, and so he addressed some of the child labor issues in his reforms at New Lanark. The climate was ripe for labor unions. “The growth of labor unionism and the emergence of the working-class into politics caused Owen’s doctrines to be adopted as an expression of the workers’ aspirations, and when he returned to England from New Harmony in 1829 he found himself regarded as their leader. The word “socialism” first became current in the discussions of the “Association of all Classes of all Nations,” which Owen formed in 1835.“

Eventually Robert Owen began to believe that no less than the total reform of society would be necessary to see his vision fulfilled. He wrote OUTLINE OF THE RATIONAL SYSTEM OF SOCIETY, FOUNDED ON DEMONSTRABLE FACTS, Developing the First Principles of the Science of Human Nature: Being the only effectual Remedy for the Evils experienced by the Population of the world; the gradual adoption of which would tranquillize the present agitated state of Society, and relieve it from moral and physical Evils, by removing the Causes which produce them. (One could never accuse Owen of thinking small!) He established Five Fundamental Facts on Which the Rational System of Society is Founded.

It should not be surprising to learn that Owen’s views were not universally accepted. It was well known that he was not a staunch, by the book, Church of England, believer. “His reading of books on religious controversies led him to conclude at an early age that there were fundamental flaws in all religions.” Indeed, in his “Declaration of Principles” Owen wrote, “I believe that to worship, by mere words or formal ceremonies, any object on the earth or in the heavens, or any thing of human device, is most opposed to the feelings of every conscientious intelligent mind, and that all such worship is necessarily destructive of the rational facilities of those trained in the practice of it.

… I believe that man cannot discover truth except by accurately investigating facts, that is true wisdom now to found a New Religion on facts only.”´(Social Bible, p. xxxiv-xxxv) Although his intention for writing this cannot be fully known, this is clearly a throwdown of the gauntlet for most church members of his time. In 1838, Frederic R. Lees, Secretary to the British Association for the Suppression of Intemperance, published Owenism dissected: a calm examination of the fundamental principles of Robert Owen’s misnamed “rational system.” He pontificated, “The principles of Christianity are now sought to be superseded by the wisdom of Robert Owen! In an insidious and roundabout way, Infidelity [by Infidelity he meant error in thinking] now demands that admittance which she could not gain by an open attack! For the Book of God, we are modestly requested to substitute the book of Robert Owen! a book, we confess, which eclipses all others, in crudeness, folly, and absurdity!“

Still, Owen had his followers, his adherents. UASC has, within a miscellaneous collection of materials about the various historical communal experiments in New Harmony, Indiana (CS 445-1-6), a copy of a document entitled Social Bible. Laws & Regulations of the Association for all Classes of all Nations. Social Hymns for the use of the Friends of the Rational System of Society. It’s dedicated to Robert Owen, and the preface says that “the disciples and admirers of the Social System have long wanted a Compendium of the principles, in a small and convenient form, for reference. …The friends of Manchester and Salford [a town near Manchester] have ever been the firm advocates of the System, and here, by their exertions, kept it in view before the public. Some few years ago they established a School upon the System, and opened their Room on Sunday evenings for Lectures and discussions on that subject, thus claiming the attention of many thinking friends, and further, to make impressions on the mind of the principals thus taught and explained” (p. iv-v). It goes on to say that since music is nearly universally popular, congregational singing or professional singing is included in the meetings to make them more pleasant. Just as hymns in a traditional church service serve to further the message, so these Social Hymns “cause the minds of the persons who attend to reflect and consider on the new principles taught to the world” (p. vi). The hymns have themes of truth, reason, charity, union, sympathy, community, peace, freedom, knowledge, temperance, and festival. A few stanzas from the hymns celebrating reason will illustrate the divergence of Owen’s and Lees’ belief systems.

Lo! Knowledge comes, and from the mind

Drives error and its dreams afar;

Now truths we all will seek and find,

Mankind no more shall practice war.

Rule, fair reason! (no. 14, p. 11)

Tis reason’s sacred lamp supplies,

These glorious works with light;

Her truths upon the nations rise,

And guides our wand’ring sight.(no.13, p. 10)

Rise, Reason! Shine on all our race,

Shed confidence around,

For where thou guid’st our wand’ring steps,

Is sure, is solid ground.(no. 15, p. 11)

Perhaps a future blog will delve more deeply into Robert Owen in New Harmony, but for now, enjoy this account of how he attempted to change the world.

**A spinning mule was a machine used to spin cotton. The mule spinners had to work in close proximity to the machine, bending over it. The spindles of the machine were lubricated with mineral oils, and threw off a mist of this oil as they spun. It is the constant exposure to this oil that caused the cancer.

Resources Consulted:

Dowd, Douglas F. Robert Owen. Encyclopedia Britannica online. May 10, 2020.

Early History & Robert Owen. Undiscovered Scotland webpage.

A Factory Worker’s Lot: Conditions in the Mill. BBC: Nation on Film, 2014.

New Lanark. UNESCO.org website—World Heritage list.

Owen, Robert. Outline of the rational system of society …. London: Home Colonization Society, 1841.

Robert Owen. British Library’s Business and Management Portal (the Portal).

Robert Owen. New World Encyclopedia website.

Robert Owen. Spartacus Educational website.

Social Bible. Laws & Regulations of the Association for all Classes of all Nations. Social Hymns for the use of the Friends of the Rational System of Society. Manchester, England: Froggatt and Richmond, 1835. CS 445-1-6 (a miscellaneous collection of materials about the various historical communal experiments in New Harmony, Indiana)